How It Is | Miroslaw Balka

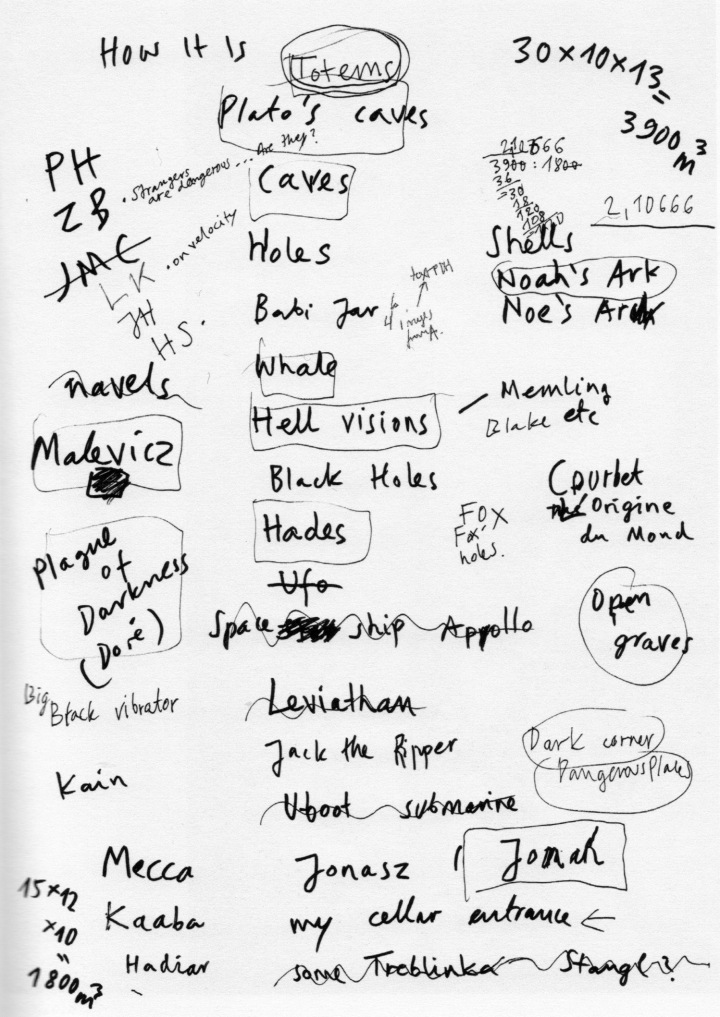

List of references for How It Is, April 2009

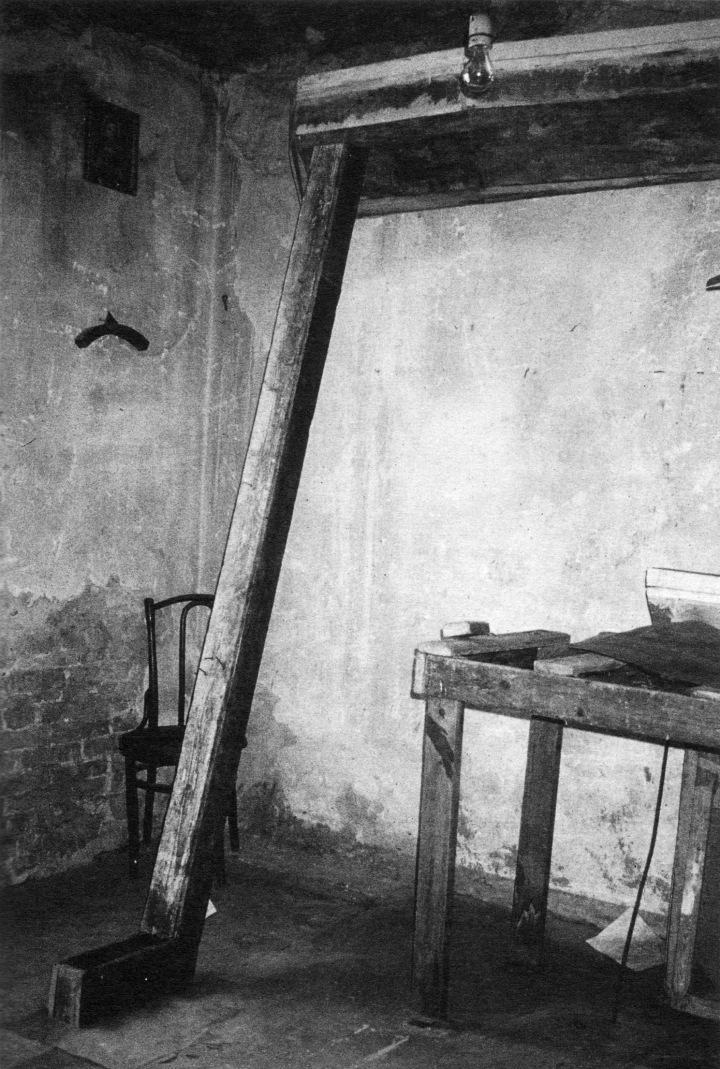

The artist’s studio with elements of Oasis (CDF), 1989

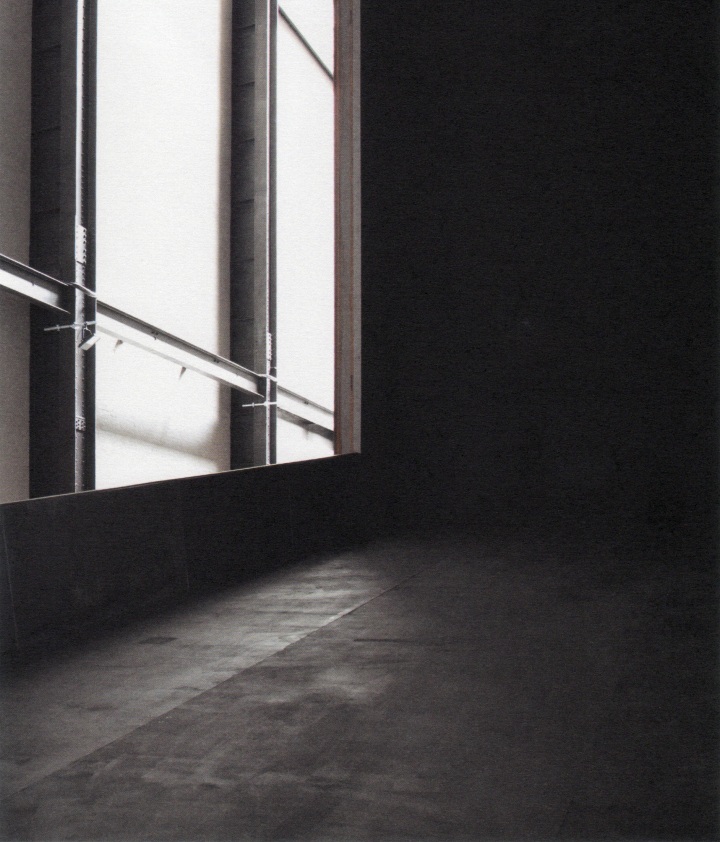

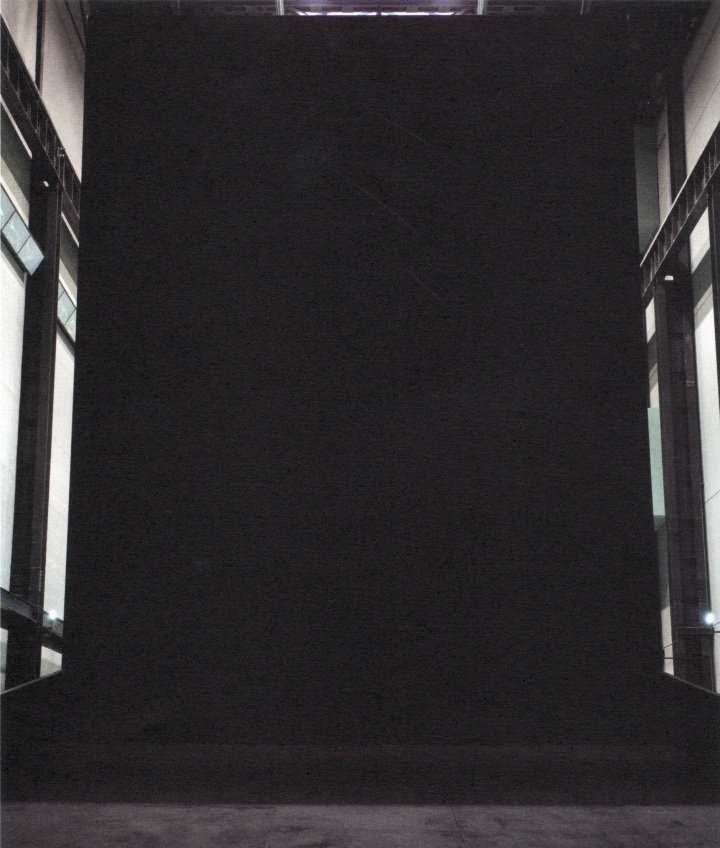

How It Is, 2009 (photography by Sam Irons)

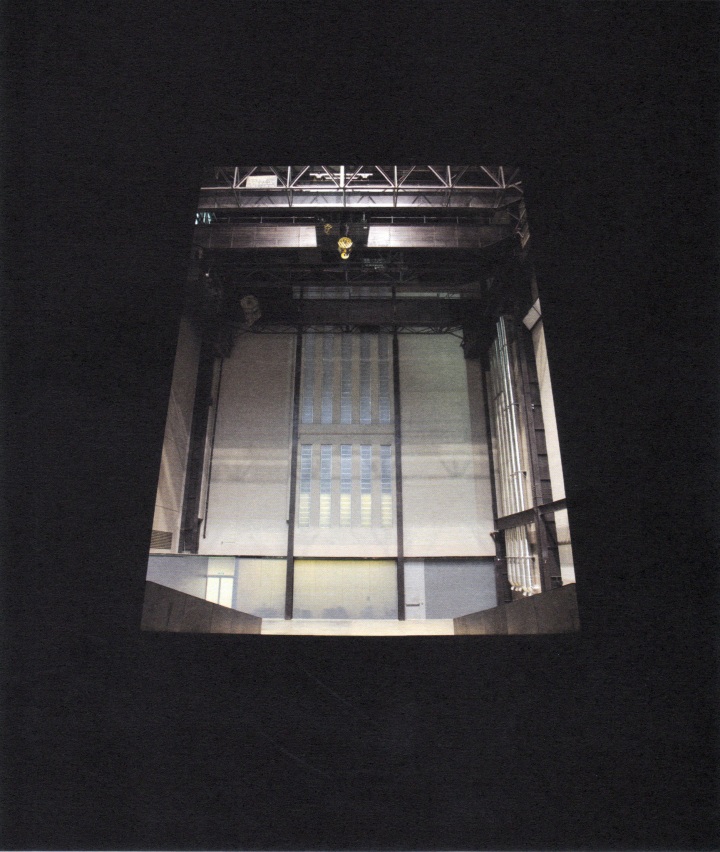

Ancient myths and the pictures of the modern era that are based on these present the domain of Hades – the shadowy realm of the dead or literally darkness, that which we cannot perceive – a place filled with a multitude of terrors. However, it is not portrayed as just another place, as the negative of this world. Particular importance also attaches to the path to Hades, the path into the underworld marked out by the travelers arrival at the river Styx, separating our world from the next, the crossing of the styx in Charon’s barque, and the moment of appearing before the god Hades. The theological, philosophical and psychological meanings of this and other descriptions of this path into death are self-evident. Of necessity they resort to recognizable metaphors to explain something that has never been seen or understood. Real burial grounds, for instance those of the Ancient Egyptians or Neolithic man in Britain, also pay particular attention to the passage from this world to the next, where effort is required to make the journey from light into complete darkness. It is only relatively recently that Balka first contemplated this zone in his work, although there are earlier shades of it here and there that dissipate into the muted twilight that pervades most of his videos. More often darkness is indirectly evoked by somewhat weak lights. Later on, when he coats the walls of the exhibition space with a two-and-a-half-meter high, continuous layer of ash, or makes a long, narrow walkway with twists and turns from simple timber, although he may literally and metaphorically be working his way toward darkness, these pieces are presented in full light of the exhibition space. No so in the case of How It Is. As the viewer approaches, it looks like a huge container, a mighty sculpture with a powerful presence. However, walking round it brings one to something else entirely, and to a sudden halt. A fragment of memory: turning the pages of the philosopher Robert Fludd’s magnum opus of 1617 the readers may find, to their surprise, a large black square taking up much of page twenty-six. ‘Et sic in infinitum’ is inscribed into all four margins of the dark square: ‘And this into infinity’, a something that one cannot imagine. The non-picture comes at the beginning of a chapter about shadows and privatio, a word that translates as both ‘privation’ and ‘liberation’. Cut. The back wall of the colossal container has been lowered, forming a ramp into the darkness. What wonder or beats await us inside? Will we have the curiosity and calm determination of János in Béla Tarr’s movie Werckmeister Harmonies to pursue the unknown, in astonishment, or will we gaze at it from the outside, uninvolved and suspicious? The steel room is large enough for its depths to be shrouded in mystery as we enter, but it is also wide enough to move about freely inside it – alone or with others. It is not pitch black inside, just increasingly dark; turning around we can still see the outside. The mise-en-scene of the unknown is overwhelming, but not because the Turbine Hall where it is placed would dwarf any smaller structure. The fact is that might raised up steel body – as tall as a house – corresponds in size to our inner sense of the unknown, of the limits of life. The effort and huge amount of material that went into making it were necessary to convey the notion, the fear, the black block that weighs us down on the last path. The sculpture had to become almost absurdly large in order to give a true sense of the threat that looms at us in the shape of the last wall in the realms of our imagination. However, when one in fact enters the black box, there is no climax to this sense of the overwhelmingly uncanny, instead there is a kind of gradual dis-illusion as one becomes accustomed to the darkness, an insight into ‘how it is’. Privatio: deprived of the certainty of life yet also liberated from the fear? The black container is a paradox. It has the dimensions of fear and is large enough to accommodate a social event, but it also has the intimacy of an individual thought and the normality of a single life.

Julian Heynen (Translated by Fiona Elliott)

___

How It Is

Miroslaw Balka : Zygmut Bauman : Julian Heyene : Paulo Herkenhoff : László Krasznahorkai : Helen Sainsbury

Tate Publishing

2009

___

Tate Channel: The Unilever Series: Miroslaw Balka

R

[…] How it is […]

[…] How it is […]