How It Is | Miroslaw Balka

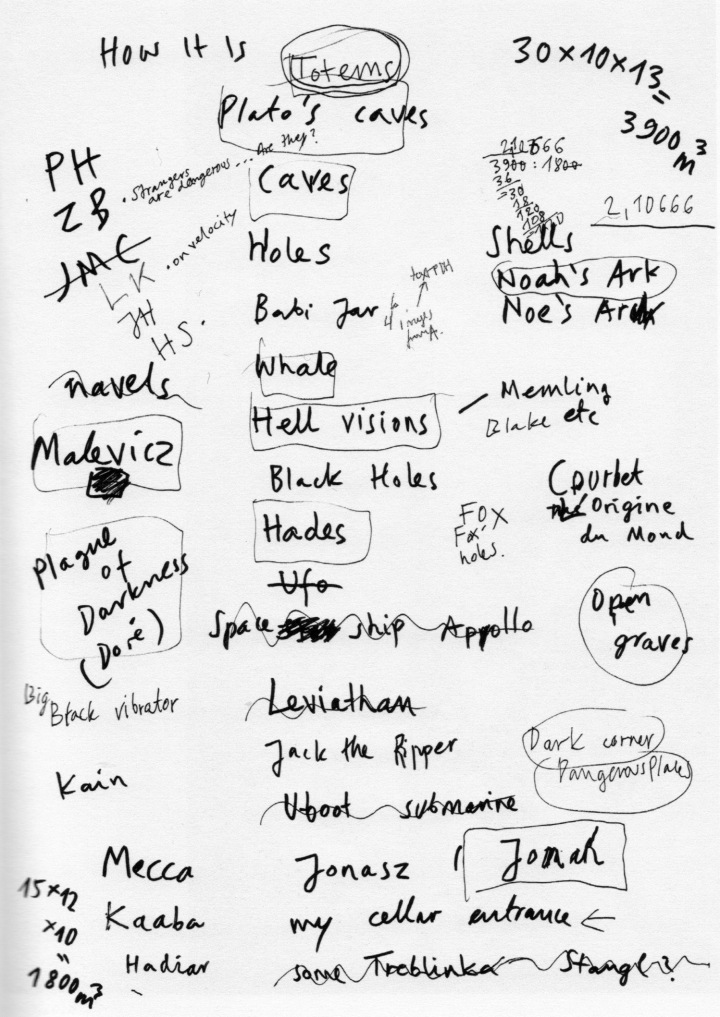

List of references for How It Is, April 2009

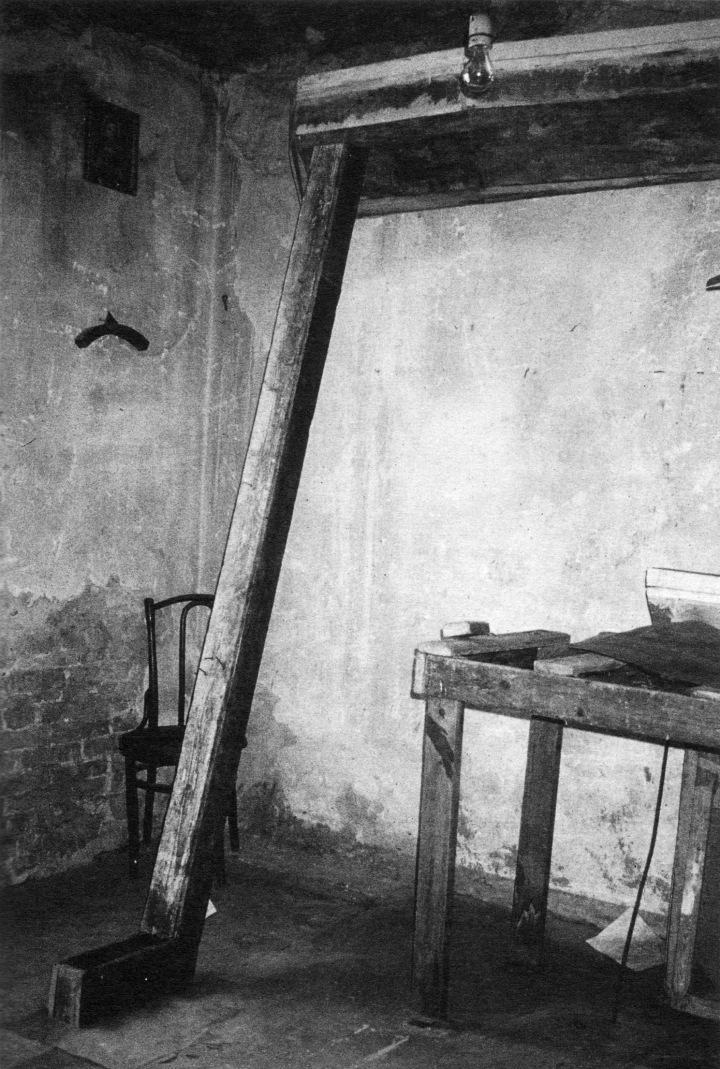

The artist’s studio with elements of Oasis (CDF), 1989

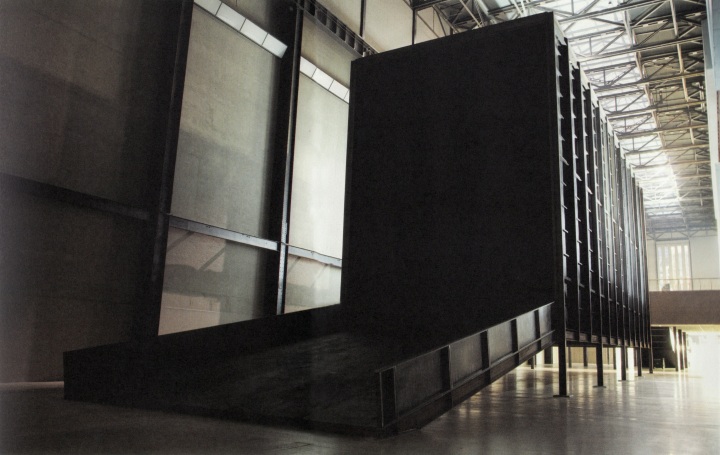

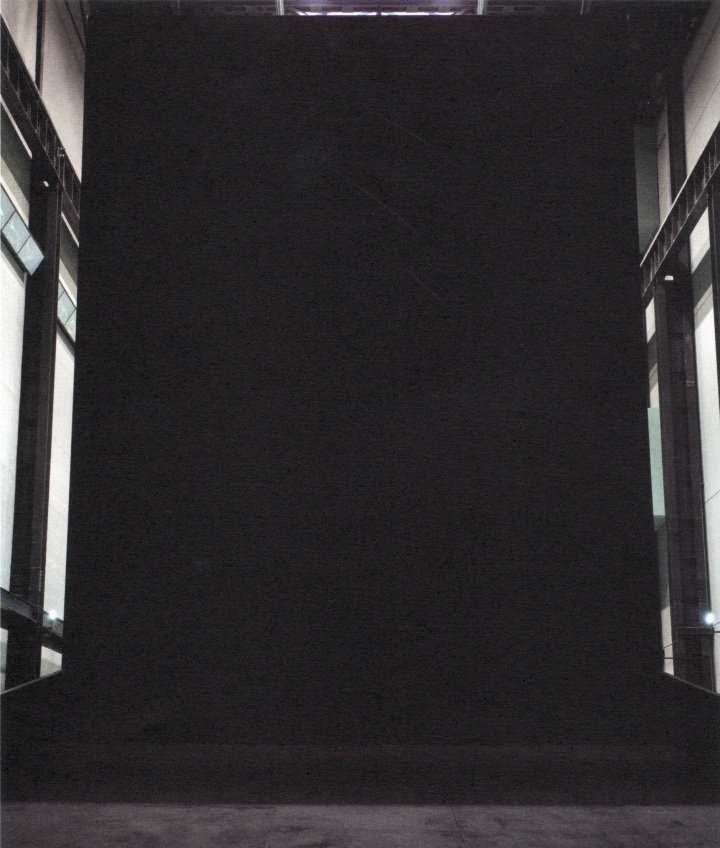

How It Is, 2009 (photography by Sam Irons)

Ancient myths and the pictures of the modern era that are based on these present the domain of Hades – the shadowy realm of the dead or literally darkness, that which we cannot perceive – a place filled with a multitude of terrors. However, it is not portrayed as just another place, as the negative of this world. Particular importance also attaches to the path to Hades, the path into the underworld marked out by the travelers arrival at the river Styx, separating our world from the next, the crossing of the styx in Charon’s barque, and the moment of appearing before the god Hades. The theological, philosophical and psychological meanings of this and other descriptions of this path into death are self-evident. Of necessity they resort to recognizable metaphors to explain something that has never been seen or understood. Real burial grounds, for instance those of the Ancient Egyptians or Neolithic man in Britain, also pay particular attention to the passage from this world to the next, where effort is required to make the journey from light into complete darkness. It is only relatively recently that Balka first contemplated this zone in his work, although there are earlier shades of it here and there that dissipate into the muted twilight that pervades most of his videos. More often darkness is indirectly evoked by somewhat weak lights. Later on, when he coats the walls of the exhibition space with a two-and-a-half-meter high, continuous layer of ash, or makes a long, narrow walkway with twists and turns from simple timber, although he may literally and metaphorically be working his way toward darkness, these pieces are presented in full light of the exhibition space. No so in the case of How It Is. As the viewer approaches, it looks like a huge container, a mighty sculpture with a powerful presence. However, walking round it brings one to something else entirely, and to a sudden halt. A fragment of memory: turning the pages of the philosopher Robert Fludd’s magnum opus of 1617 the readers may find, to their surprise, a large black square taking up much of page twenty-six. ‘Et sic in infinitum’ is inscribed into all four margins of the dark square: ‘And this into infinity’, a something that one cannot imagine. The non-picture comes at the beginning of a chapter about shadows and privatio, a word that translates as both ‘privation’ and ‘liberation’. Cut. The back wall of the colossal container has been lowered, forming a ramp into the darkness. What wonder or beats await us inside? Will we have the curiosity and calm determination of János in Béla Tarr’s movie Werckmeister Harmonies to pursue the unknown, in astonishment, or will we gaze at it from the outside, uninvolved and suspicious? The steel room is large enough for its depths to be shrouded in mystery as we enter, but it is also wide enough to move about freely inside it – alone or with others. It is not pitch black inside, just increasingly dark; turning around we can still see the outside. The mise-en-scene of the unknown is overwhelming, but not because the Turbine Hall where it is placed would dwarf any smaller structure. The fact is that might raised up steel body – as tall as a house – corresponds in size to our inner sense of the unknown, of the limits of life. The effort and huge amount of material that went into making it were necessary to convey the notion, the fear, the black block that weighs us down on the last path. The sculpture had to become almost absurdly large in order to give a true sense of the threat that looms at us in the shape of the last wall in the realms of our imagination. However, when one in fact enters the black box, there is no climax to this sense of the overwhelmingly uncanny, instead there is a kind of gradual dis-illusion as one becomes accustomed to the darkness, an insight into ‘how it is’. Privatio: deprived of the certainty of life yet also liberated from the fear? The black container is a paradox. It has the dimensions of fear and is large enough to accommodate a social event, but it also has the intimacy of an individual thought and the normality of a single life.

Julian Heynen (Translated by Fiona Elliott)

___

How It Is

Miroslaw Balka : Zygmut Bauman : Julian Heyene : Paulo Herkenhoff : László Krasznahorkai : Helen Sainsbury

Tate Publishing

2009

___

Tate Channel: The Unilever Series: Miroslaw Balka

R

Himmel-Herde | Anselm Kiefer

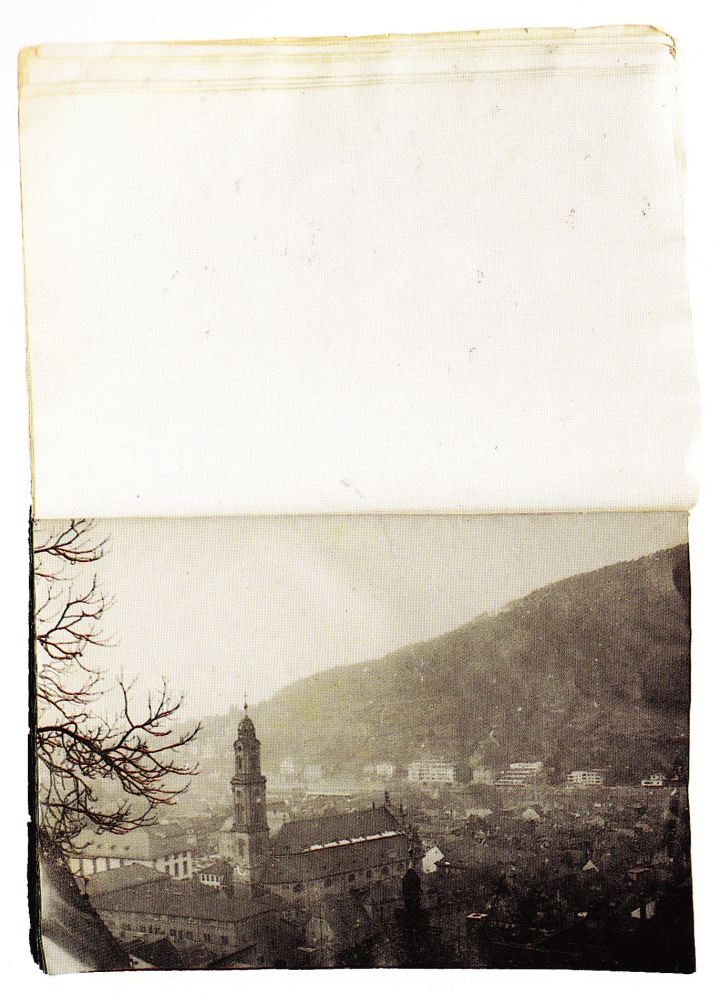

Die Überschwemmung Heidelbergs I, 1969

Die Überschwemmung Heidelbergs I, 1969

Die Überschwemmung Heidelbergs I, 1969

Die Überschwemmung Heidelbergs I, 1969

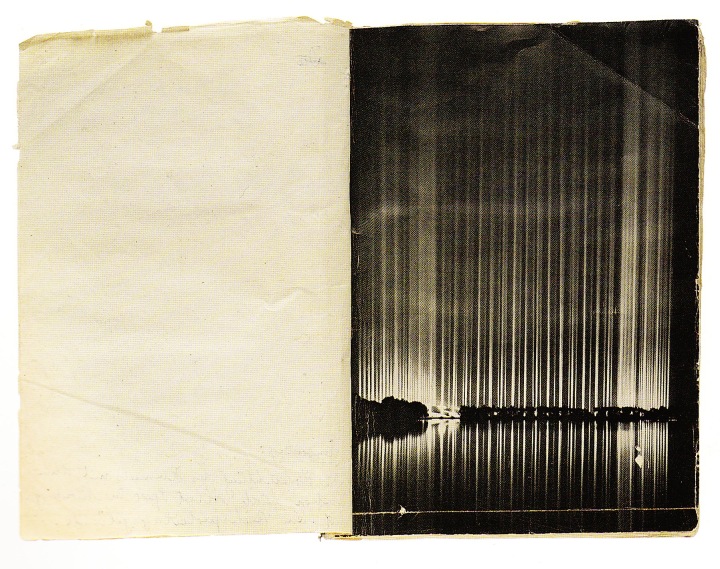

Die Himmel, 1969

Die Himmel, 1969

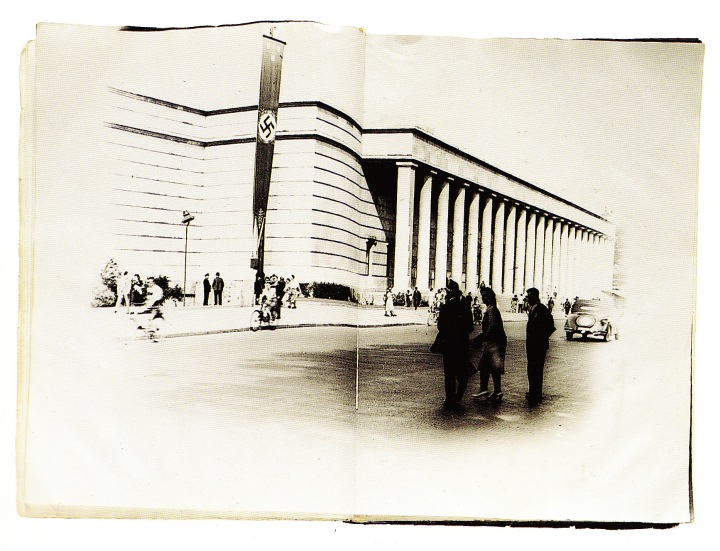

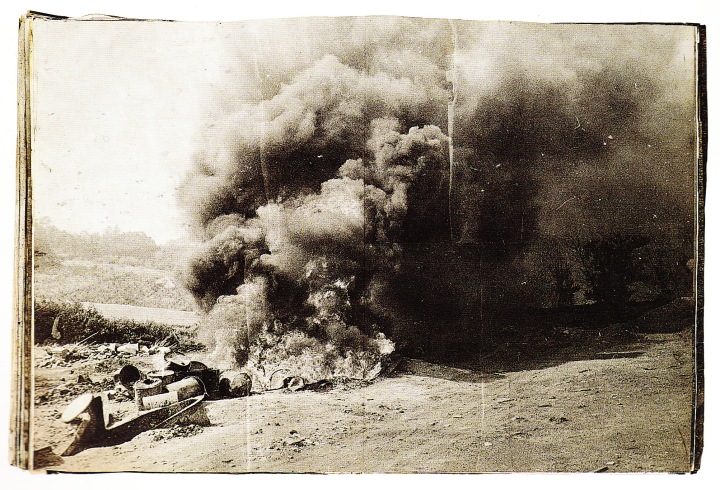

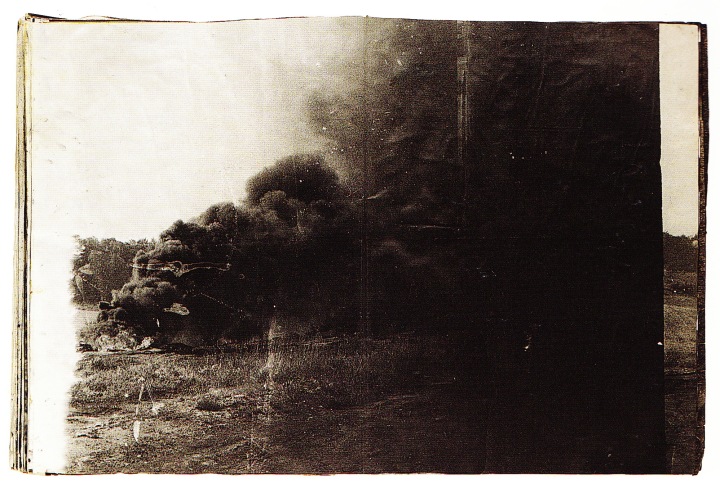

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

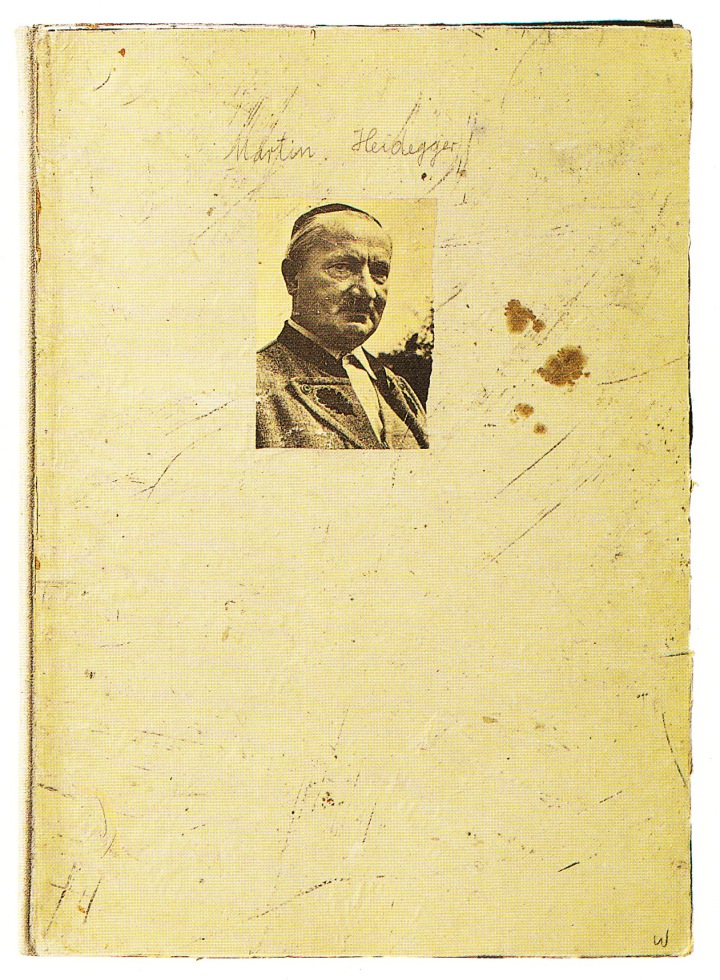

Martin Heidegger, 1976

Martin Heidegger, 1976

Martin Heidegger, 1976

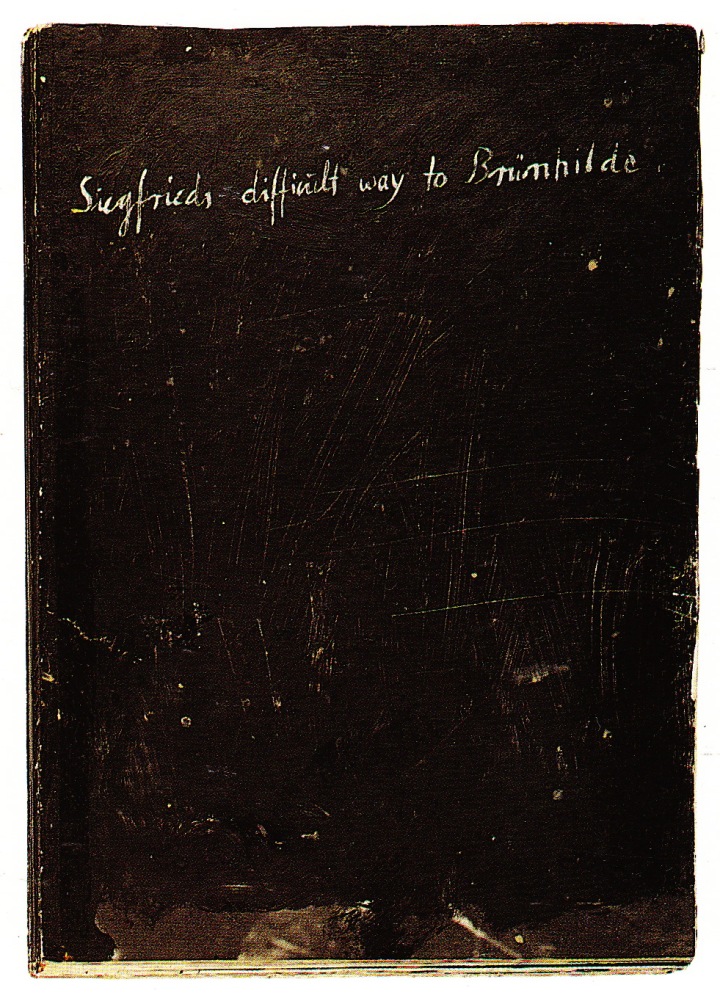

Siegfried’s Difficult Way to Brunhilde, 1977

Siegfried’s Difficult Way to Brunhilde, 1977

Siegfried’s Difficult Way to Brunhilde, 1977

Siegfried’s Difficult Way to Brunhilde, 1977

When, in order to adapt to his destiny as an artist, Anselm Kiefer attempts to throw himself open to a dimension larger than himself, he does not retreat in the face of a force that may overwhelm and daunt him. He allows himself to be possessed and swept away by it, to become the arbiter of a challenge which ultimately implies the construction of the formal energy of art. To let ourselves be overwhelmed means to agree to be impregnated and to mediate that which submerges and overtakes us: to discover ourselves in order to discover. The artist, like the poet, eludes any system, whether good or bad, religious or moral: he negates himself, dies in favour of an unknown and indefinable force, and aspires to establish the right relationship with forms and their origins. He wants to succumb to their primacy and lets himself be shattered and overwhelmed not for any banal or general reason, whether it be ideological or sociological, anonymous or impersonal, but only for one exceptional reason: the survival of the language of art.*

*The Destiny of Art: Anselm Kiefer by Germano Celant.

___

Himmel-Herde : Anselm Kiefer

Massimo Cacciari : Germano Celant : Gabriele Nason : Emanuela Belloni

Edizioni Charta

1997

___

B

Robert Smithson

Aerial view of Spiral Jetty (1970), Great Salt Lake, Utah, August 2003. Mud, precipitated salt crystals, rocks and water. Coil: 1500 ft. long and 15 ft. wide. Photographed by David Maisel.

Smithson building Spiral Jetty (1970), Great Salt Lake, Utah, 1 April 1970. Photographed by Gianfranco Gorgoni.

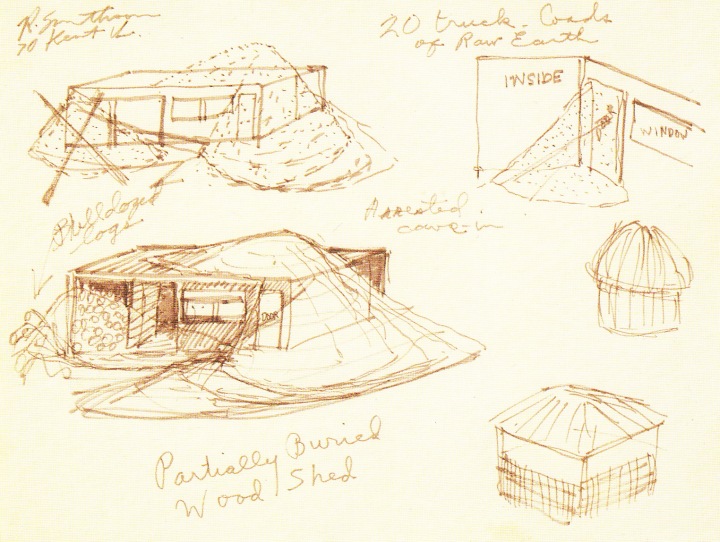

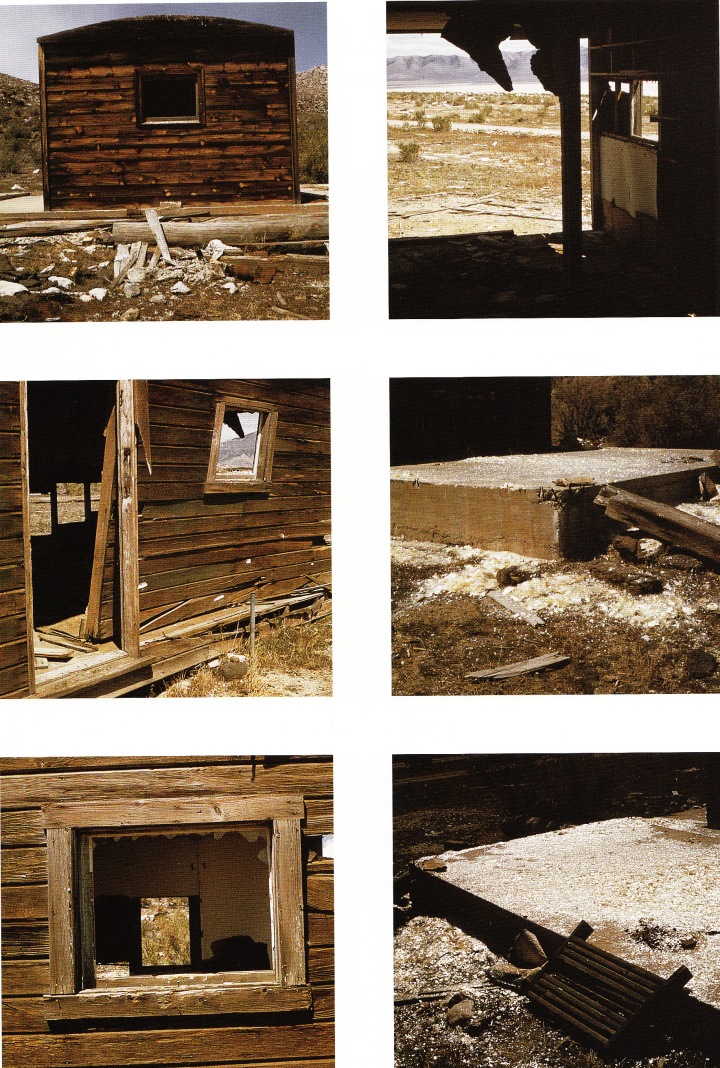

Documentary Drawings for Partially Buried Woodshed, 1970.

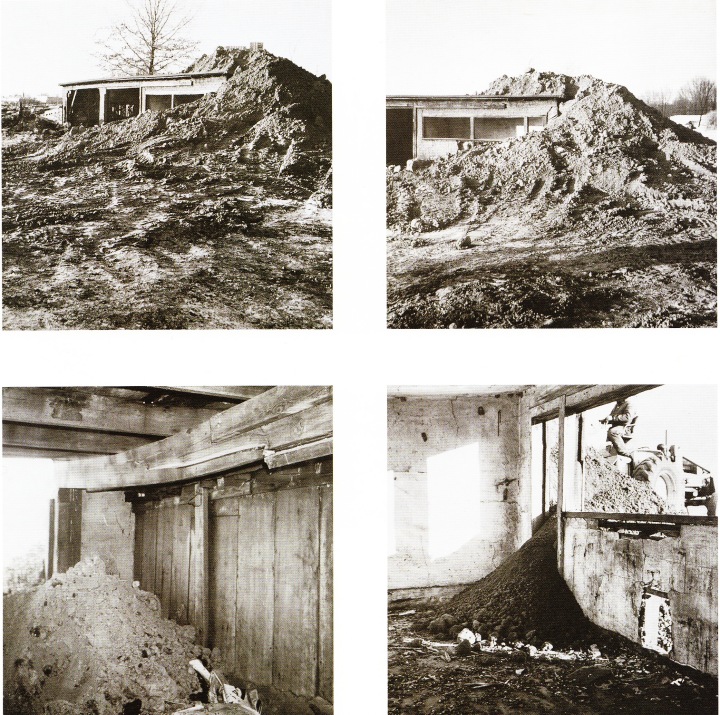

Partially Buried Woodshed, 1970.

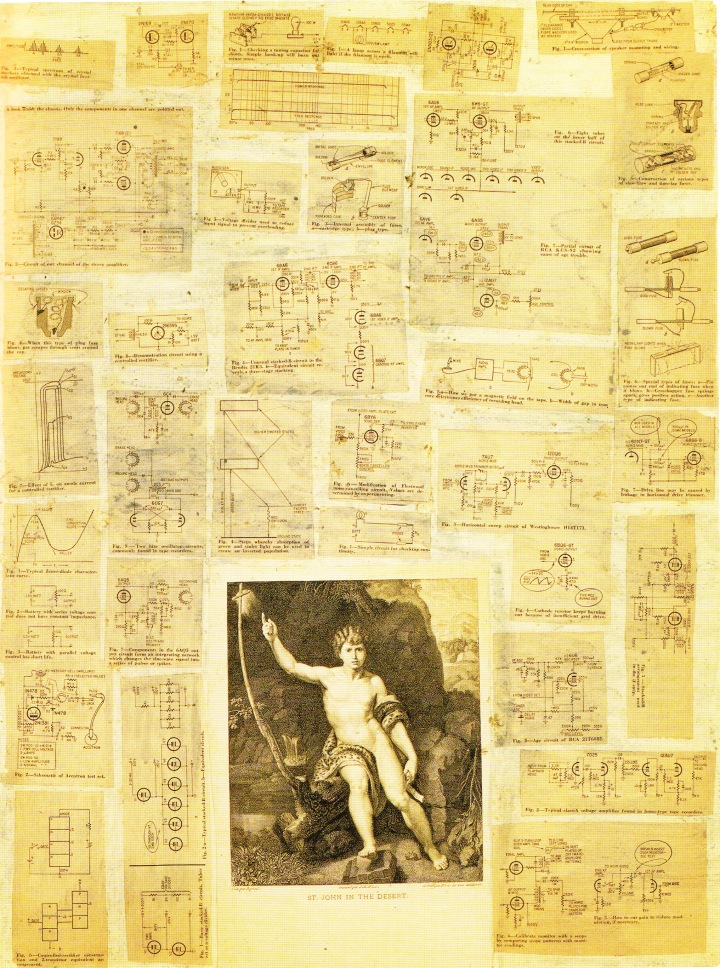

St. John in the Desert, c. 1961-63.

Untitled (Mica Spread) (1970), Rozel Point, Utah, April 1970. Photographed by Nancy Holt.

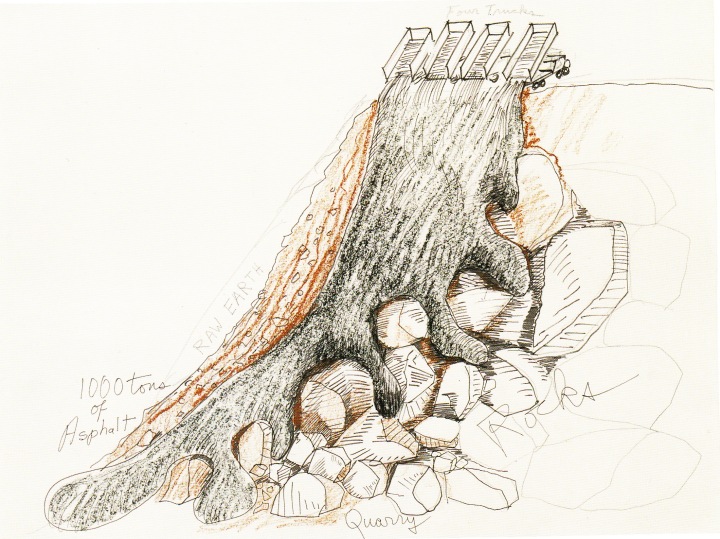

1000 Tons of Asphalt, 1969.

Asphalt Rundown, Rome, 1969.

Spiral Jetty (1970), Great Salt lake, Utah, 1970. Mud, precipitated salt crystals, rocks and water. Coil: 1500 ft. long and 15 ft. wide. Photographed by Gianfranco Gorgoni

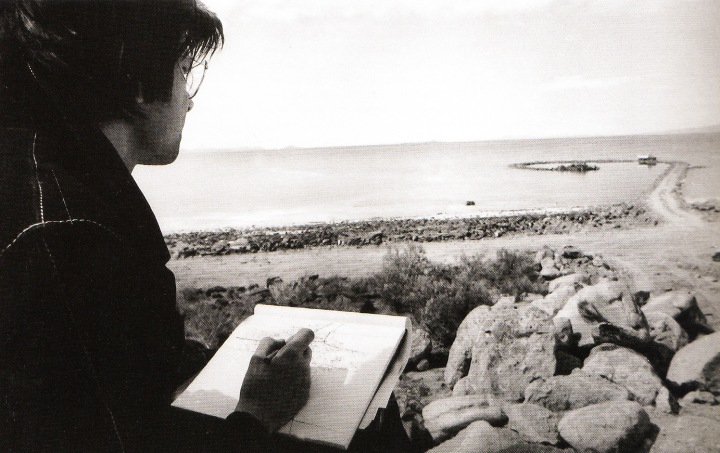

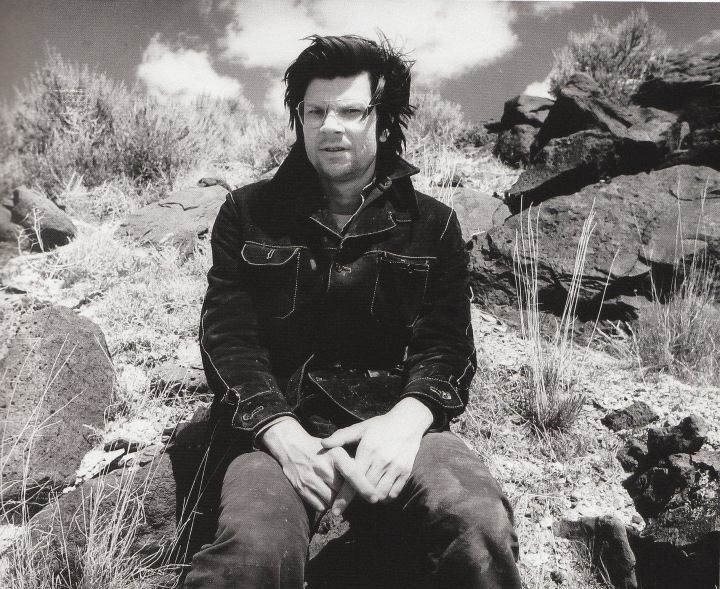

Smithson at the site of Spiral Jetty (1970), Great Salt Lake, Utah, April 1970. Photographed by Gianfranco Gorgoni.

Robert Smithson is perhaps best known as a pioneer of the Earthworks movement and the creator of the iconic Spiral Jetty (1970). However, his involvement in the development of Earthworks is only one of his many contributions to postwar American art. One of the most important concepts Smithson was that of the “site,” a place in the world where art is inseparable from its context. His sites included remote locations like Rozel Point, on the north shore of the Great Salt Lake; the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico; the art museum and the white cube of the gallery; and the pages of art magazines like Artforum, where he published some of his essays. By encompassing both conventional exhibition venues and far-flung locations within his practice, Smithson performed a kind of institutional critique, pointing to the geographical and cultural limitations that the purportedly neutral spaces of museums impose on art.

___

Robert Smithson

Eugene Tsai : Cornelia Butler

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

2005

___

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

B

Maison Martin Margiela

Store in Los Angeles, Beverly Hills _ Opened on September 5th, 2007 _ Images of architectural details such as doors, stucco and moldings from Maison Martin Margiela’s former premises in Paris are are printed on transparent films

A/W 1990-91 _ Women’s show _ backstage

S/S 1990 _ Tabi boots with hand-tagged graffiti

A/W 2000-01 _ Cooperation magazine, oversized collection feature and snap shots of looks

1999 – Door sign, Boulevard Saint-Denis (headquarters of the Maison from 1990 to 1994)

A/W 2008-09 _ Women’s show, backstage

Headquarters, Paris _ Special installation in the rue Saint-Maur showroom

October 2008 _ Special and limited edition Tabi-boot shaped candle, Sent as a gift to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Maison Martin Margiela

Headquarters, Paris _ Dress forms in Martin Margiela’s studio, Boulevard Saint-Denis (headquarters of the Maison from 1990 to 1994)

S/S 2005 _ Arena Homme+ _ Line 0 _ Peter Doherty wearing a shirt printed with lipstick kisses

S/S 2007 _ Line 0 _ Invitation to the presentation of the ‘Artisanal’ collection, in the form of white embroidery on starched white cotton. It has maintained this form for every season since S/S 2006

A staff member on the stairs at the Paris headquarters, rue Saint-Maur

S/S 1998 _ View on colour _ Interview

Headquarters, Paris _ Workshop in the Maison Martin Margiela rue Saint-Maur offices

Store in Osaka _ opened on August 28th, 2003 _ Invitation and shoe display

Headquarters, Paris _ Men’s commerical showroom _ The custom made trunk and white tailors dummy’s identify the Line 14 concept: A classic and timeless wardrobe for men

The past is what binds us,

The future leads us.

___

Maison Martin Margiela

Rizzoli

2009

___

The Cult of Invisibility by Lucian James

R

Sachlich | Christian Boltanski

Objets confisqués par les Nazis et déposés au Musée Central des Juifs, Prague

(Items confiscated by the Nazis and deposited in the Central Jewish Museum, Prague)

1941-1945

Inventaire des objets ayant appartenu à une femme de Baden-Baden

(Inventory of items that belonged to a woman from Baden-Baden)

1973

Les habits de François C.

(The clothes of Francis C.)

1972

Objets trouvés dans les égouts de Zurich pendant la semaine du 1er au 10 Juin

(Items found in the sewers of Zurich during the week of 1 to June 10)

1994

Sachlich (Objective), part of a four part series that comprises Kiddish, surveys Boltanski’s principal motifs of place, memory and loss.

The banal tenor and specificity of context in Boltanski’s still-lifes introduce an interesting dialogue as the tonality and depth, or lack thereof, in his photographs render what are reasonably delicate subjects, into mute and objectified echos from a nonspecific time or place. Boltanski’s infatuation with confiscated war relics, (post-) belongings and objet trouvé presented throughout his tetrad make reference to the anonymity and translucence of memory, the interstitial space between sentimentality and indifference, and ultimately focus on transience, singularity and, often forced, despondency. These topos are poignantly represented in the thin vellum leaves of Sachlich that obscure and adumbrate the overleaf images, possessing the lucidity and vagrant non-specificity of memory itself.

Boltanski’s canon analyses notions of detachment and ephemerality in peculiar ways; monolithic aggregates of found and disregarded objects, candles and oxidized copper, or works of stone bare insight into an artist who’s works, ideologies and prehistory are often conflicting. Having absented himself from formal education in his preteens, Boltanski moved from rudimentary sculpture, drawing and painting to installations of pensive and introspective sculptural, filmic, and photographic works; questioning his own substance and significance in relation to memory, lineage and cultural praxis – the multidisciplinary nature and varied scale of these installations characterizes his work to date. An undercurrent throughout Boltanski’s work, and something that can often be difficult to grasp, is the over-simplification, and to a large degree the denial, of intellectual reason. When Boltanski’s work seems to display a profound melancholy or contemplation on histories past, it is the artist who abruptly categorizes his works as quotidian debris, coincidence or ‘stupid’ objects – stating that that it is ‘simply much easier to be dead, than to be alive.’*

___

Sachlich

Christian Boltanski : Toni Stooss : Catrin Wesemann

KUNSTHALLE Wien

1995

___

R

Joseph Beuys and the Celtic World

Joseph Beuys (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Beuys completing the Brain of Europe drawing for his Hearth installation at the Royal Feldman Gallery, New York 1975 (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Beuys at Sandycove, where James Joyce lived before leaving Ireland for Europe (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Beuys investigating the plant life of Ireland, November 1974 (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Performing Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony, 1970 (photographed by Richard Demarco).

Beuys at the Giant’s Causeway, Antrim, Northern Ireland, c.1970 (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Forrest Hill Poorhouse doors, c.1980 (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Caroline Tisdall in conversation with Sean Rainbird, 2001.

Sean Rainbird: Is there a single work in the Bits and Pieces collection that has an especial importance for you?

Caroline Tisdall: There are many themes running through the collection; lots about alchemy, humour, about plants and the transformation of energy. Interconnecting Vases [Two Vases with Precious Water 1975] is probably one of the definitive images in this collection. It was made with blood and insulin, when Beuys was in hospital in 1975 following his heart attack. He was having treatment in Düsseldorf before he went to the spa in Bad Rothenfelde.

SR: So it commemorates a private event, when his health was endangered and he was physically at his most vulnerable?

CT: It is a symbol of love, friendship and reciprocity. ‘C’ and ‘D’ [Cosmas and Damian] with the cross, the triangle and, at the bottom ‘J’ and ‘C’, which could be Joseph and Caroline. The triangle is usually a trinity symbol. In all my earlier writings, I must confess I rather suppressed the Christian angle, but should acknowledge it more now. We did talk about it a lot. Fundamental to his work was the transformation of material and I think you almost have to be brought up a Catholic to use that as a creative principal.

I am a Celt and a total pagan. We often talked about spirituality. By the 1980’s he was certainly not a practicing Catholic. … But there were many elements of Catholicism he kept, like the reincarnation of souls. He also had some fundamental ideas about death and what it means as a destination. In this collection, on an ironic level, is the Hat For Next Time [1974]. After his encounter with the Dalai Lama in 1975 he was very attracted, in later life, to Buddhism. It led to the Amsterdam conference Art meets Science some years later.

It shows in his work with Nam June Paik – particularly the works with the flame. It wasn’t exclusively a Buddhist flame though; think of his saying ‘schütze die Flamme’ (guard the flame). That connects to German philosophy and produces echoes in different cultures. He was confident talking about things which were very difficult to talk about or even taboo; Braunkreuz [‘brown cross’, the distinctive brown pigment Beuys used], the German oak. He felt himself to have grown up in a Catholic, Celtic enclave [in Cleves]. The Lower Rhine is a strange spiritual place, literally quite cut off from Germany like a bend in the river.

SR: What part does language play in this?

CT: He was very deeply rooted in the German language. His whole idea of rehabilitating Germanic imagery and symbols was because he felt that any country which cannot look at its own history is built on foundations of sand and will turn more and more to modern materialism which completely denies spirituality. He felt that was really dangerous not only because of materialism, but also because of a backlash; politically, a spin back into neo-Nazism. One so wishes he had been there when Germany was reunified [in 1989] and the whole spiritual vacuum was exposed, comparing the legacy of both forms of materialism; capitalist materialism and de-spiritualised, grey, Eastern materialism.

SR: Do these sentiments come to a head in any place in Germany you visited, or in any symbolic taboos he confronted?

CT: We went to Externstein in 1975 when he was still recovering from his heart attack. It was a day trip to an absolute taboo place, as it was one of Hitler’s shrines to the Germanic spirit. All the Germanic gods were meant to be there; one of those fat fertility goddesses was dug up there. He wanted his photograph taken with his hand over his heart. What came out was a de-politicized image. It was tongue-in-cheek but like an oath-swearing gesture. He has the confidence to do that. just like the 7000 Oaks project [1982, Kassel] which was growing in his mind at the time. The oak is the symbol that you find on the Iron Cross [a military decoration]. The Nazis had really tried to subsume it into their hierarchy of symbols. As Beuys always said, it is terrible to deny the ‘oakness’ of your countryside just because of the Nazis. If you do that, you deny your own culture, your own history. In Bits and Pieces, the earliest work is an oak-leaf drawing from 1957, a collage, the earliest I have ever seen [Untitled]. I think it is an incredible drawing, so perfect. It has his old-fashioned signature, the early sort, on the bottom right.

SR: Can his use of Braunkreuz be viewed in light of your comments about national identity?

CT: The same goes for that brown colour. That terrible Nazi thing of ‘blood and earth’ [Blut und Boden]. He actually dared to take materials like that and use them, and he reinstalled them in the canon of their ‘Germanness’.

…

SR: I have always been intrigued by his use of Gothic script at certain points in his career.

CT: Gothic script has its own history. If we were German we would feel sad it fell of of use because of the Nazis. Beuys wanted to undermine the misuses and reappropriate the sources. You have to remember Heinrich Böll too, doing a huge examination of the German spirit in his writing, in books like The Lost Honour of Katharine Blum and Faces of a Clown.

SR: How well did they know one another?

CT: Beuy’s friendship with Böll was very significant. You can follow it through the decades. Böll always used to apologize for being boring! Beuys always had difficulty reading his work, of getting beyond Chapter One. They knew each other well enough for him to feel how it went on after that. The Organization for Direct Democracy through Referendum and the Free International University for Interdisciplinary Research [FIU] were both collaboration with Heinrich Böll. It was was great for Beuys to have a kindred spirit like that on his level, and vice versa…

…

SR: At what point did he intimate that he was building a collection for you. Or did it become obvious over time that this was happening?

CT: That’s a very interesting question. I’ve never thought about it. Everything with Beuys happened in such a natural way, but I imagine that by the time whole sets of things came, like the four botanical drawings Rosemary, Calendula (Marigold), Nasturtium, Pomegranate [all 1975], he was obviously building up to something. Rosemary is obviously for remembrance. And he was very fond of my mother, who was a Shakespearean actress in her younger days. And I was born in Stratford-upon-Avon. So rosemary features in the botanical things. Then calendula, which is an incredibly important homeopathic plant. When he sent it it was an amazing orange like the sun.

The collection reflects pretty accurately what was going on while it was being formed. He then actually suggested exhibiting it, and we showed it at Paul Negau’s Generative Art Gallery in 1976. By then it had its main themes: its Celtic and botanic themes, its mystical theme, alchemy and politics. The other thing there from the beginning was his interest in language: plays on words and the examinations of puns, differences between languages and curious things about English. Like the riddle in Three Hares 1975: ‘Drei Hasen und die Ohren drei und doch hat jeder seiner zwei’ (if there are three hares and three ears, how can each hare have two ears?).

…

SR: What strikes me is that it is a very practical lexicon, not a set of instructions, but a densely planted approach to someone’s art. You can read a lot of these objects very directly.

CT: Absolutely. It gives you the homeopathic, the herbal, Rudolf Steiner, biodynamics, concerns with nature as a whole, the environment, the imbalance of the spirit and the material. These run through the whole block.

SR: He seemed to have a special gift of allowing a small object to speak volumes about complex issues and projects.

CT: Take the bandage, for instance, issued to German soldiers during the war [Untitled 1977]. If you put that in a vitrine it becomes monumental; it gives you the theme of the war and a whole phase of his autobiography, and in signing such an object, he claimed it’s whole history.

…

Bits and Pieces 1957-85, [is] a rich body of objects, drawings and multiples compiled over a decade by the artist for the writer and filmmaker Caroline Tisdall. Numbering around 300 items Bits and Pieces constitutes a comprehensive lexicon of the artist’s material and ideas.

___

Joseph Beuys and the Celtic World | Scotland, Ireland and England 1970-85

Sean Rainbird

Tate Publishing

2005

___

R

Heaven and Earth | Anselm Kiefer

Studies for The Seven Heavenly Palaces, Barjac, 1973-2001

October 5, 2004 | Barjac

Michael Auping: Titling an exhibition Heaven and Earth, as we have done here, requires a little explanation. Perhaps we should just begin with the very simple question, do you believe in heaven?

Anselm Kiefer: The title Heaven and Earth is a paradox because heaven and earth don’t exist anymore. The earth is round. The cosmos has no up and down. It is moving constantly. We can no longer fix the stars to create an ideal place. This is our dilemma.

MA: And yet we keep trying to find new ways to get to ‘the ideal place’, the place we assume we came from – to find the right direction.

AK: It is natural to search for our beginnings, but not to assume it has one direction. We live in a scientific future that early philosophers and alchemists could not foresee, but they understood very fundamental relationships between heaven and earth, that we have forgotten. In the Sefer Hechaloth, the ancient book that came before the kabbala, there is no worry of directions. It describes stages, metaphors, and symbols that float everywhere. Up and down were the same direction. The Hachaloth is the spiritual journey toward perfect cognition. North, south, east, and west, up and down are not issues. For me, this also relates to time. Past, present, and future are essentially the same direction. It is about finding symbols that move in all directions.

…

MA: You are not a ‘New Age’ spiritualist. I know that for sure, but some people who see your images may wonder just what your position is in regard to religion.

AK: My spirituality is not New Age. It has been with me since I was a child. I know that in the last few decades religion has been made shiny and new. It’s like a business creating a new product. They are selling salvation. I’m not interested in being saved. I’m interested in reconstructing symbols. It’s about connecting with an older knowledge and trying to discover continuities in why we search for heaven.

MA: I can see fragments of continuity in your works between symbols that are ancient and those that take a more modern form, and for me that suggests a kind of hope within your landscapes. But there are also some very dark shadows in your images, literally in terms of color , as well as in metaphor and content. It is as if in the same image we see a liberation of knowledge but the dark weight of history.

…

MA: Christian images are apparent in your work, but in many ways not as apparent as Jewish or Gnostic references.

AK: Later, I discovered that Christian mythology was less complex and less sophisticated than Jewish mythology because the Christians limited their story to make it simple so that they could engage more people and defend their ideas. They had to fight with the Jewish traditions, with the Gnostics. It was a war of the use of knowledge. However, it wasn’t just a defense against outside ideas. It was aggressive. Like politics, they wanted to win. You know, the first church in Rome was not defensive and not aggressive. It was quiet. It was spiritual in the sense of seeking a true discussion about God. It was exploring a new idea about humanity. But then there was ‘iglesias triumphant’, the Triumph of the Church. And then the stones were stacked up and the buildings came, and the construction of the Scholastics, Augustine, and so on. They were very successful in limiting the meaning of the mythology. There were discussions about the Trinity and its meaning. anyone who had ideas that complicated their specific picture was eliminated. This made Christianity very rigid and not very interesting. Whenever knowledge becomes ridgid it stops living.

MA: In 1966, you visited the Monastery at La Tourette. Was this before you made the decision to be an artist?

AK: I began studying law. I didn’t study law to be a lawyer, but for the philosophical aspects of law, constitutional law. I was interested in how people live together with out destroying each other.

I went to La Tourette while I was studying law. It may sound strange to go from the study of law to La Tourette, but it really wasn’t. I had always been interested in law from a spiritual aspect. A constitution is not unlike the idea of a church doctrine. People need a context or a content, something to bind them together. This could be stretched to mythologies. Law, mythology, religion – they are all structures for investigating human character.

…

MA: Why did you go to La Tourette in the first place? I don’t imagine that you went only to see a Le Corbusier building. You stayed there for three weeks.

AK: The Dominicans were there. I liked their teaching. They have an interesting history. I had read that they had many discussions with Le Corbusier about the shape of the building and the materials. It was a point in my life when I wanted to think quietly about the larger questions. Churches are the stages for transmitting knowledge, interpreting knowledge and ideas of transcendence. It’s a history of conflicts and contradictions. A church is an important source of knowledge and power. Le Corbusier knew that. I stayed there for three weeks in a cell. I thought about things. In a place like that you are not simply encouraged to think about God but to think about yourself, Erkenne dich selbst. Of course, you think about your relationship to god.

Also, for me it was an inspiring building in the sense that a very simple material, a modern material, could be used to create a spiritual space. Great religions and great buildings are part of the sediment of time; like pieces of sand. Le Corbusier used the sand to construct a spiritual space. I discovered the spirituality of concrete – using earth to mould a symbol, a symbol of the imaginative and spiritual world. He tried to make heaven on earth – the ancient paradox.

…

MA: Could we go back and talk a little bit more about your education as an artist? You went to the university in Freiburg.

AK: Yes. But first I had a nineteenth-century idea that the artists is a genius – that art comes out of him naturally and he doesn’t need any education. I had always thought this, even as a child. You could say that I had too much admiration for artists. I thought they all came from heaven. Later I found out than an artwork is only partly done by the artist, that the artist is part of a larger state of things – the public, history, memory, personal history – and he must just work to find a way through it all, to remain free but connected at the same time.

…

MA: And later on you went to see Joseph Beuys, although you didn’t officially study with him.

AK: No. I was living in the forrest in Hornbach and had made some canvases. I had heard of Beuys and so I took my canvases to Düsseldorf to show him. He was impressive. I liked him very much. His dialogue was broad and he could be very impressive. He had a world view, not just the view of an artist. I think I appreciated him more because I had studied law.

MA: How so?

AK: Art cannot live on itself. It has to draw on a broader knowledge. I think both of us understood that at the tim ewe knew each other.

MA: Although I never met him, you and Beuys seem very different to me. He was more extroverted and you are more introverted, or at least less public.

AK: We were different, and as a young artist I needed to question that difference. Nevertheless, I learned a lot from him, even though he was not my teacher. I could talk to him about larger issues.

MA: In his interviews and writings, Beuys often evoked the word ‘spiritual’. How do you think he meant that?

AK: That is complicated. We were both in Germany at a certain time – a time when a dialogue about history and spirituality needed to begin. It was difficult to separate the two subjects There was a sense of starting over. To evoke the spiritual not only looking at ourselves but into the history of our nation. It was not just a matter of a critique. It had to be deeper than that. So yes, Beuys was a spiritual man. The artist is naturally spiritual because he is always searching for new beginnings.

…

MA: Here on the grounds of your home in Barjac, France, you are creating a monumental installation of stacked concrete rooms or ‘palaces’ that go up hundreds of feet into the air, asa well as a sprawling series of connected underground tunnels and spaces containing palettes, books, and lead rooms. Are you working your way through the palaces of heaven?

AK: I follow the ancient tradition of going up and going down. The palaces of heaven are still a mystery. The procedures and formulae surrounding this journey will always be debated. I am making my own investigation.

___

Heaven and Earth

Anselm Kiefer

Prestel

2005

(The catalogue is published on the occasion of the exhibition Anselm Kiefer: Heaven and Earth organized by Michael Auping for the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth)

___

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

R

The Matter of Time | Richard Serra

Forming of the plates for The Matter of Time at Pickhan Umformtechnik, Siegen, Germany

Serra (center) and others installing One Ton Prop (House of Cards) at the Museum of Art, RISD, Providence, 1969

Robert Smithson and Richard Serra, 1970

Frames from Hand Catching Lead, 1968

Tilted Arc, 1981. Weatherproof steel, cylindrical section tilted into the ground, 12′ x 120′ (3.66 x 36.58 m), plate thickness 2½” (6.5 cm). General Services Administration, Washington D.C. Installed at Federal Plaza, New York, 1981-89; destroyed by the United States Government, 1989.

Installation of To Encircle Base Plate Hexagram, Right Angles Inverted at 183rd Street and Webster Avenue, Bronx, New York, 1970.

Shift, 1970-72. Concrete, six sections; section one: 5′ x 240′ (1.52 x 73.15 m); section two: 5′ x 150′ (1.52 x 45.72 m); section three: 5′ x 120′ (1.52 x 36.57 m); section four: 5′ x 105′ (1.52 x 32 m); section five 5′ x 110′ (1.52 x 33.52 m); section six 5′ x 90′ (1.52 x 27.43 m); section thickness: 8″ (20 cm). Installed in King City, Ontario, Canada.

Serpentine, 1993. Weatherproof steel, two units, each comprised of two conical sections, each section: 13’2″ x 52′ (4 x 15.85 m); length overall: 104′ (31.7 m): plate thickness 2″ (5 cm). Collection of Frances and John Bowes, Sonoma, California.

Torqued Ellipse II, 1996. Weatherproof steel, 12′ 29′ x 20’5″ (3.66 x 8.83 x 6.22 m); plate thickness: 2″ (5 cm). Dia Art Foundation. Gift of Leonard and Louise Riggio.

Afangar (Stations, Stops on the Road, to Stop and Look: Forward and Back, to Take It All In), 1990. Basalt, eighteen stones; nine: 9’10” x 1’9″ x 1’9″ (3 x .55 x .55 m): nine: 13’1½” x 1’9″ x 1’9″ (4 x .55 x .55 m). City of Reykjavik, Iceland. Installed Videy Island, Reykjavik Harbor.

Richard Serra, photographed by Robert Frank, 2002

The List:

To roll, to crease, to fold, to store, to bend, to shorten, to twist,

to dapple, to crumple, to shave, to tear, to chip, to split, to cut,

to sever, to drop, to remove, to simplify, to differ, to disarrange,

to open, to mix, to splash, to knot, to spell, to droop, to flow,

to curve, to lift, to inlay, to impress, to fire, to flood, to smear,

to rotate, to swirl, to support, to hook, to suspend, to spread,

to hang, to collect –

of tension, of gravity, of entropy, of nature, of grouping,

of layering, of felting –

to grasp, to tighten, to bundle, to heap, to gather, to scatter,

to arrange, to repair, to discard, to pair, to distribute, to surfeit,

to complement, to enclose, to surround, to encircle, to hide,

to cover, to wrap, to dig, to tie, to bind, to weave, to join,

to match to laminate, to bond, to hinge, to mark, to expand,

to dilute, to light, to modulate, to distill –

of waves, of electromagnetism, of inertia, of ionization,

of polarization, of refraction, of simultaneity, of tides, of reflection,

of equilibrium, of symmetry, of friction –

to stretch, to bounce, to ease, to spray, to systematize,

to refer, to force –

of mapping, of location, of context, of time, of carbonization –

to continue.

The “Verb list” established a logic whereby the process that constituted a sculpture remains transparent. Anyone can reconstruct the process of the making by viewing the residue.

The sculptures resulting from the “Verb list” introduced two aspects of time: the condensed time of their making and the durational time of their viewing.

Both tasks and materials were ordinary. I was tearing lead in place, lifting rubber in place, rolling and propping lead sheets, and melting lead and splashing it against the juncture between wall and floor. The activities were experimental and playful. It wasn’t the question of how to accomplish this or that, nor was it the question of making it up as I went along: it was rather a free-floating combination of both.

I cannot overemphasize the need for play, for in play you don’t extract yourself from your activity. In order to invent I felt it necessary to make art a practice of affirmative play or conceptual experimentation. The ambiguity of play and its transitional character provides suspension of belief whereby a shift in direction is possible when faced with a complexity that you don’t understand. Free from skepticism, play relinquishes control. Play allows one to accept discontinuities and continuities; it also allows one to happen upon solutions or invent them. However, even in play the task must be carried out with conviction. It’s how we do what we do that confers meaning on what we have done.

– Richard Serra (excerpt from Questions, Contradictions, Solutions, 2004)

___

The Matter of Time

Richard Serra : Hal Foster : Carmen Giménez : Kate D. Nesin

Steidl

2005

(This publication accompanies the installation of The Matter of Time at the Guggenheim Bilbao. Curated and organized by Carmen Giménez. Sponsored by Arcelor)

___

R

Jannis Kounellis

Senza Titolo. 1975. Studio d’Arte Contemporanea, Rome

Senza Titolo, 1993. Palazzo Fabroni, Pistoia

Senza Titolo, 1983. Ateneumin Taidemuseo, Helsinki

Senza Titolo, 1969. Modern Art Agency, Naples

Senza Titolo, 1980. Galleria Mario Pieroni, Rome

Senza Titolo, 1994. Jean Bernier Gallery, Athens

Senza Titolo, 1999. Inglesia de San Augustin, Mexico City

Senza Titolo, 1976. Galleria Salvatore Ala, Milan

Senza Titolo, 2003. Torrione Passari, Molfetta

Senza Titolo, 1980. Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Ghent

Senza Titolo, 2000. Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, Valmontone

Senza Titolo, 1996. Piazza del Plebiscito, Naples

Senza Titolo, 2006. Halle Verrière, Meisenthal

Senza Titolo, 2005. MADRE – Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina, Naples

“It’s not for this form or another, but for creating the possibility of life, no? An attempt to open something outside these walls of convention. With our work we try to open an unconventional road to language, because language is stereotyped and in using language it constantly stereotypes itself. Our task is this: to find the means of opening more ways to communicate. This is what I believe.” – Jannis Kounellis.

Born in Piraeus in 1936 but living in Rome since the mid-fifties, Jannis Kounellis is considered a seminal contributor to the radically and internationally influential Arte Povera group. Literally meaning ‘Poor Art’, this began as an anti-elitist movement promoting a new openness towards artistic production, characterised by the use of antithetical materials such as sacks, beans, metal, coal, coffee, wool and gas. These unusual materials help the artist to manifest visceral “pictures” conveying a sense of the forgotten forces of an archaic world. Often epic in scale, Kounellis’s work possesses a grandeur that reflects his frequent choice of themes and ideas from the past and particularly from Ancient Greece.

Kounellis began his career as a painter, inspired in part by the work of American abstract artists of the 1950s. However, during the 1960s he abandoned traditional painting in favour of a host of everyday materials with which he created sculptures and installations, using wool, coal, iron, stones, earth, wood and even, controversially, live animals. As a result ordinary objects and natural matter hold a poetic directness and immediacy for Kounellis who is seeking to establish more concrete communication between the viewer and the artwork.

___

Jannis Kounellis

Angela Schneider: Anke Daemgen: Marc Scheps: Melanie Wilkin: Elisabeth Campolongo

Hatje Cantz

2008

___

B

2 comments