A Question of Faith | Colin McCahon

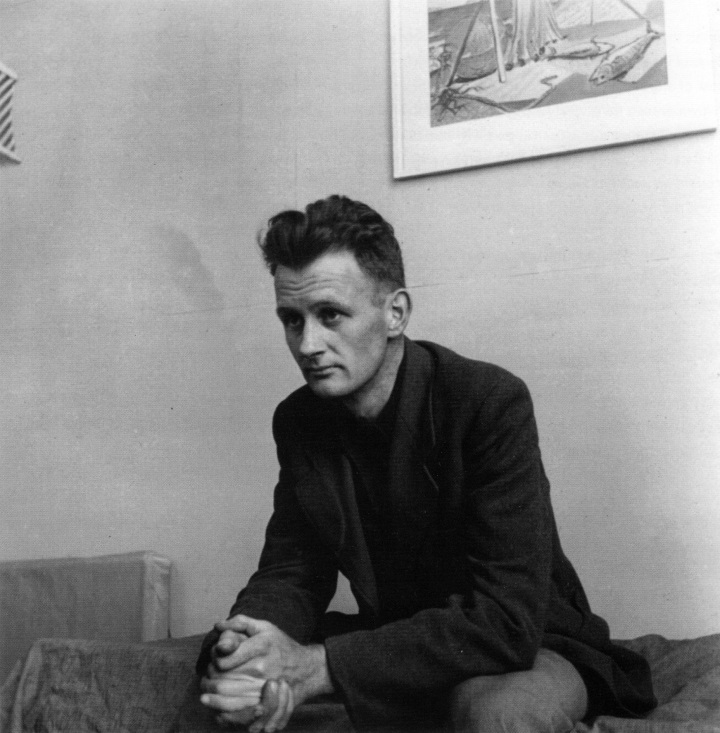

Colin McCahon, c. 1950. Courtesy of the Doris Lusk Estate.

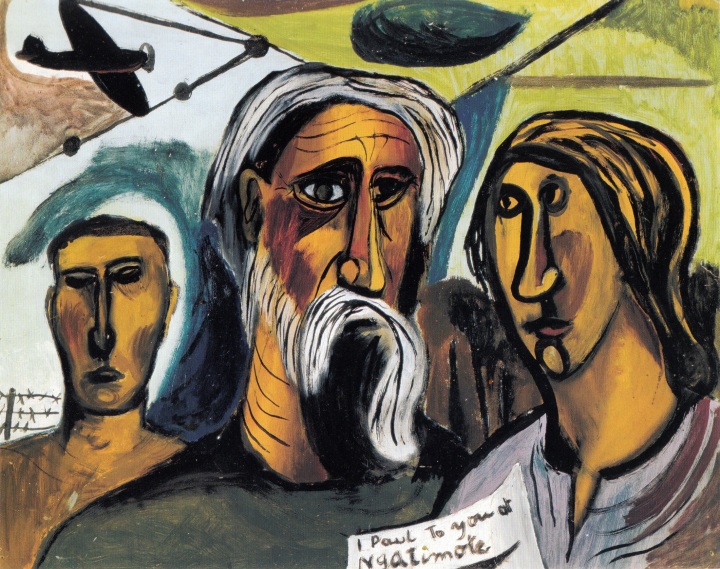

I Paul to you at Ngatimote, 1946.

Oil on cardboard, 50.5 x 63.5 cm.

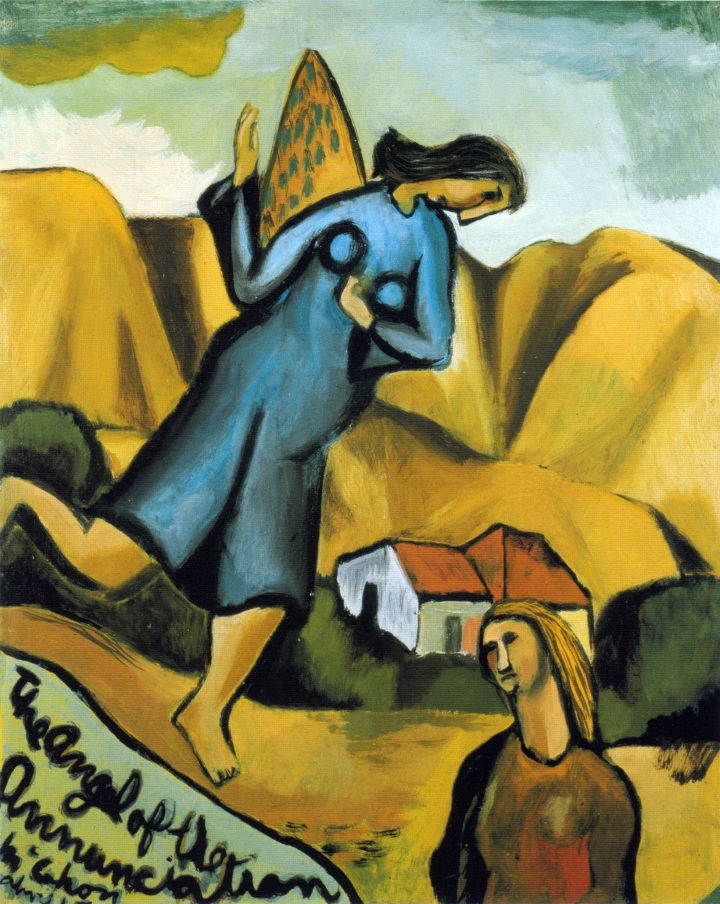

The Angel of the Annunciation, 1947.

Oil on cardboard, 63.5 x 51.2 cm.

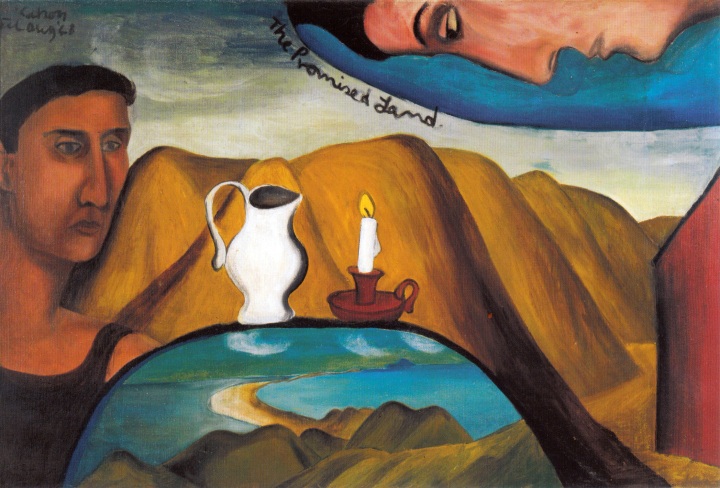

The Promised Land, 1948.

Oil on canvas, 92 x 137 cm.

The King of the Jews, 1947.

Oil on cardboard mounted on hardboard, 63.6 x 52 cm.

North Otago Landscape, 1951.

Oil on canvas on board, 51.5 x 66.2 cm.

Six days in Nelson and Canterbury, 1950.

Oil on canvas laid on board, 88.5 x 116.5 cm.

Cross, 1959.

Enamel on hardboard, 121.9 x 76.2 cm.

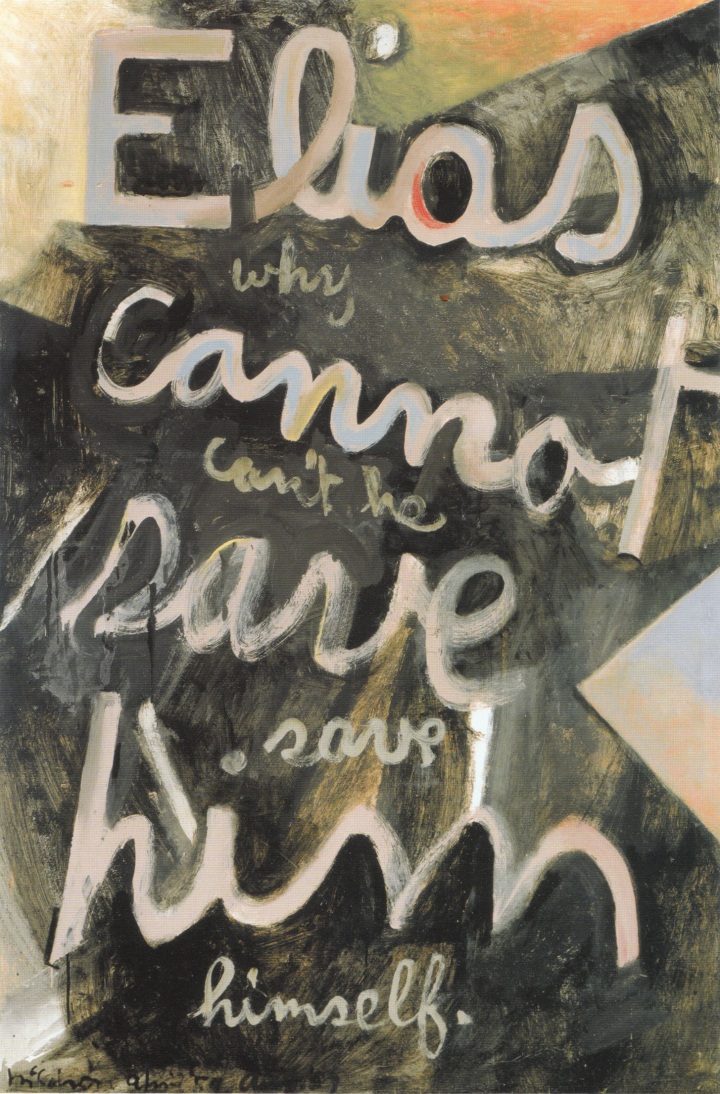

Elias: why can’t He save Himself (Elias series), 1959.

Enamel and sawdust on hardboard, 147.5 x 100 cm.

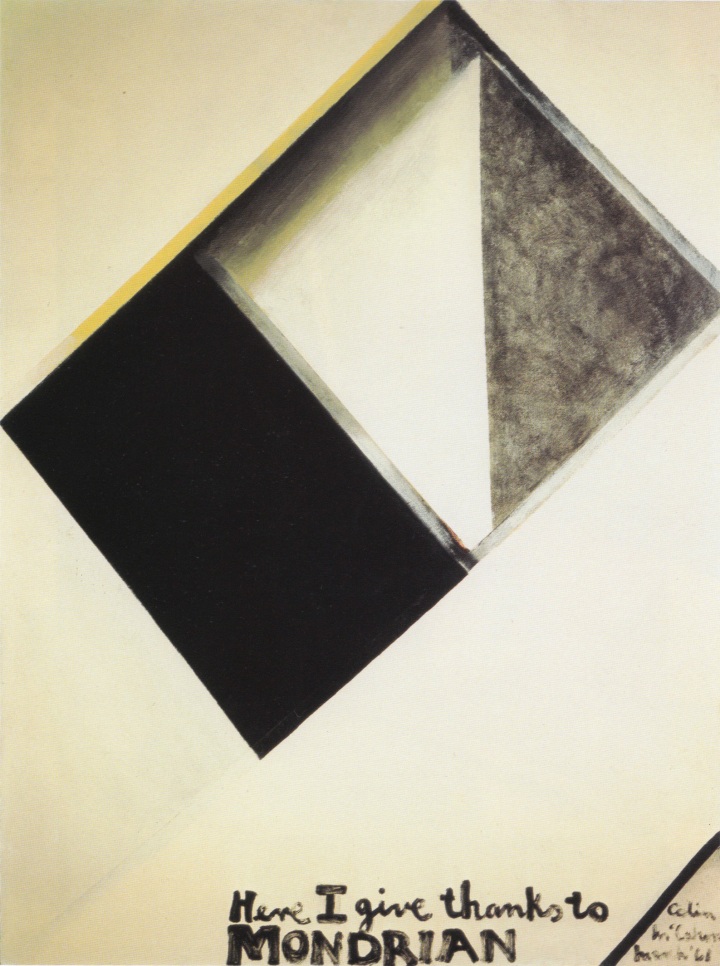

Here I give thanks to Mondrian, 1961.

Enamel on hardboard, 121.8 x 91.4 cm.

![095 Waterfall [one panel from a polytych], 1964](https://historyofourworld.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/095-waterfall-one-panel-from-a-polytych-1964.jpg?w=720&h=1701)

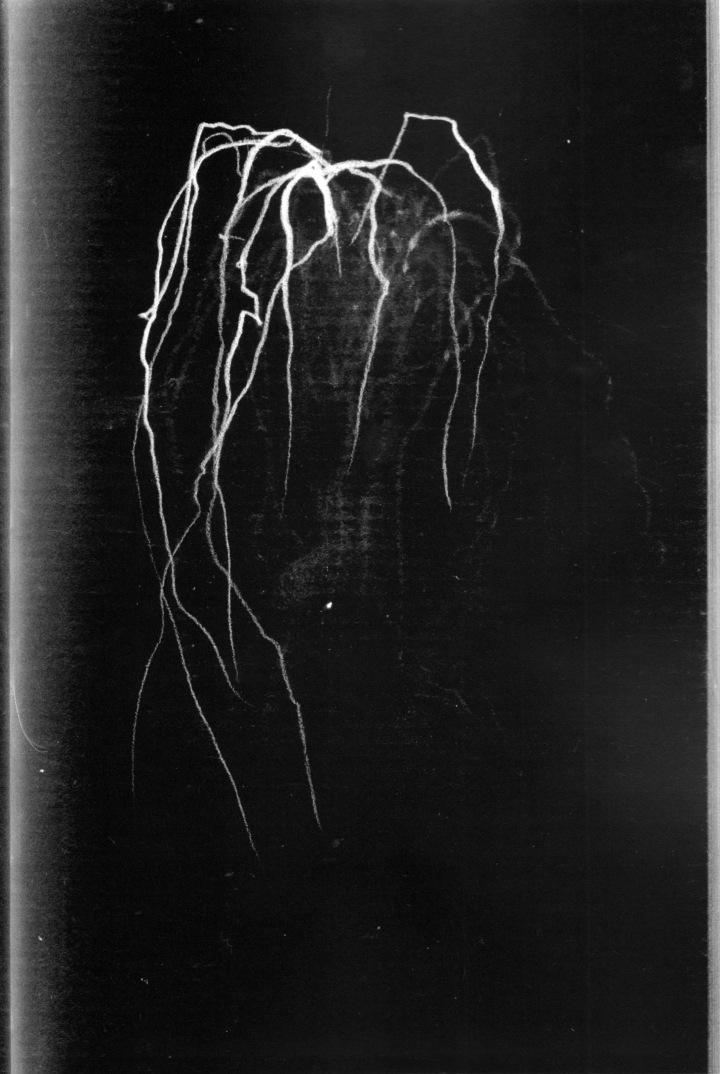

Waterfall [one panel from a polytych], 1964.

Enamel on plywood panel, 212.7 x 90.5 cm.

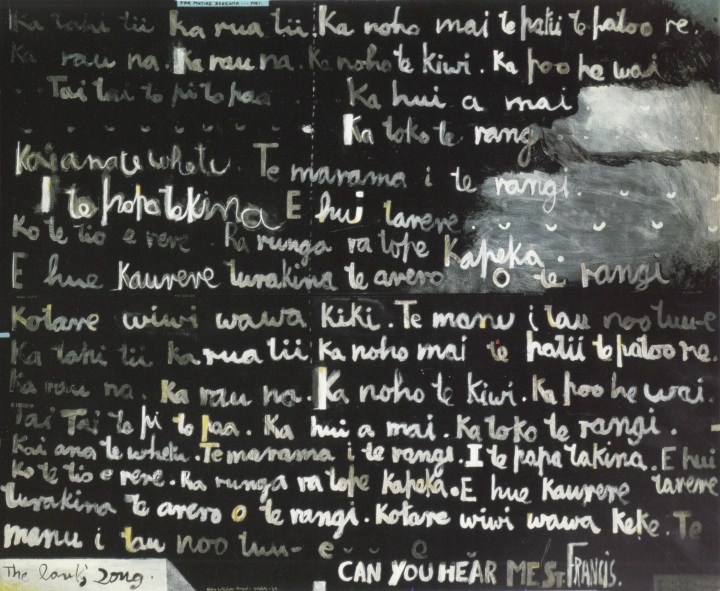

The Lark’s Song (a poem by Matire Kereama), 1969.

Acrylic on two wooden doors, overall 162.6 x 198 cm.

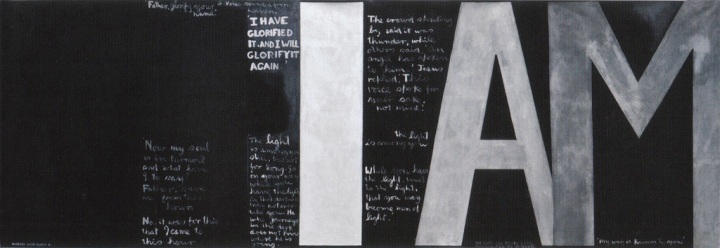

Victory over Death 2, 1970.

Acrylic on unstretched canvas, 207.5 x 597.7 cm.

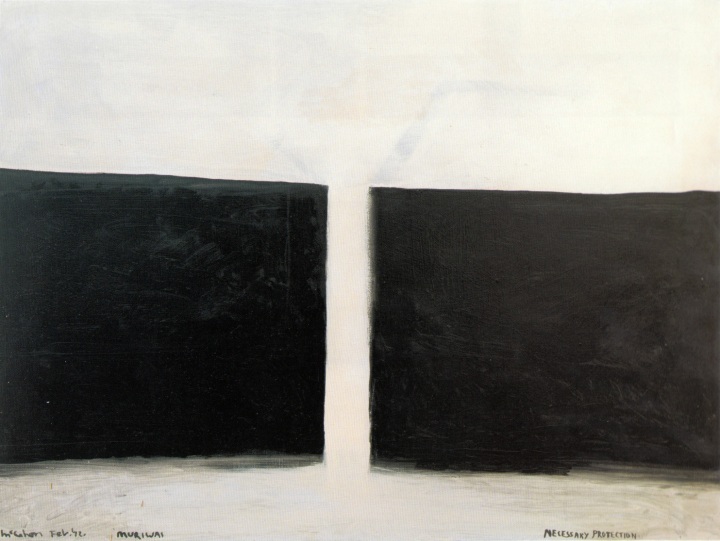

Muriwai. Necessary Protection, 1972.

Acrylic on hardboard, 60.8 x 81.2 cm.

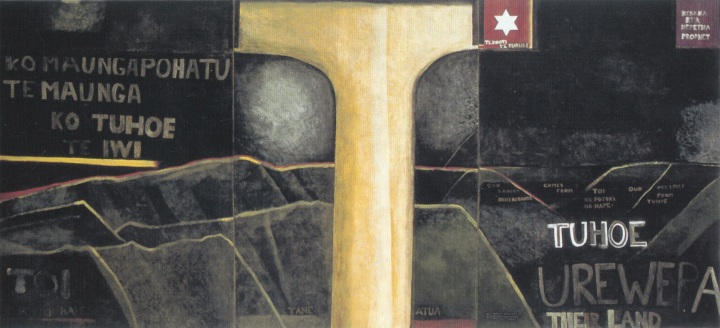

Urewera Mural, 1975.

Acrylic on three unstretched canvases, overall 255 x 544.5 cm.

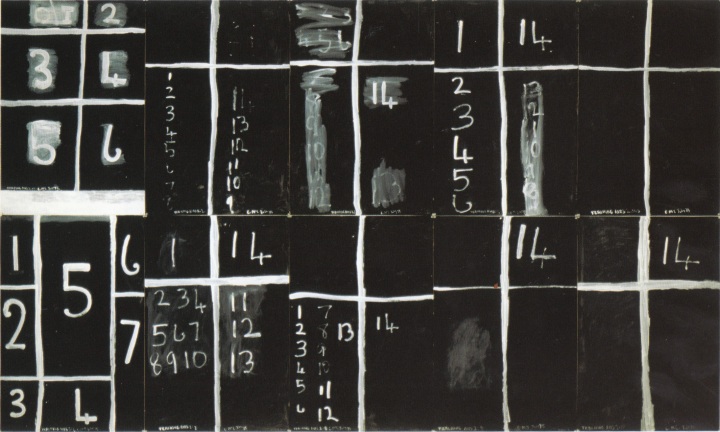

Teaching Aids 2 (July), 1975.

Acrylic on Steinbach paper, 10 sheets, each 109.2 x 72.8 cm, overall size 218.4 x 364 cm.

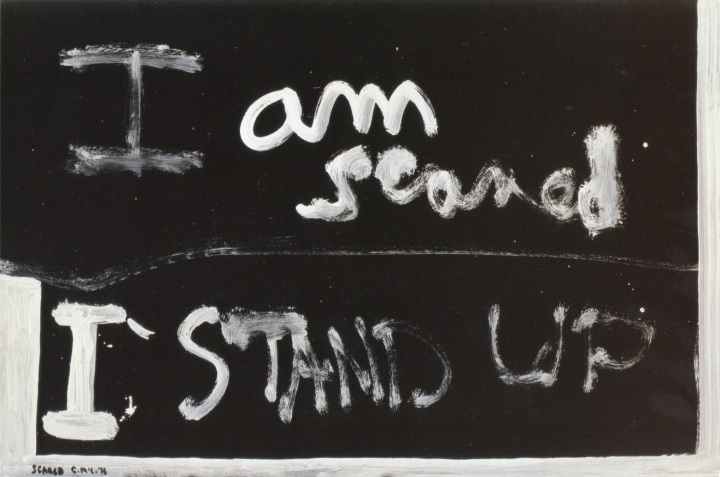

Scared, 1976.

Acrylic on Steinbach paper, 71.5 x 107 cm.

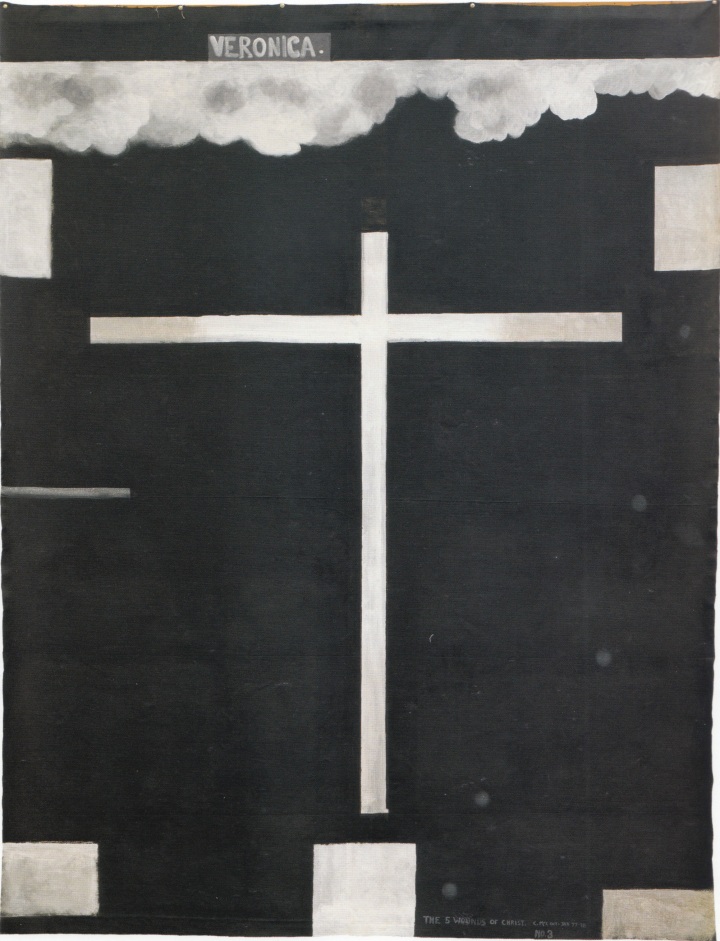

The 5 Wounds of Christ no. 3: Veronica, 1977-78.

Acrylic on unstretched canvas, 242 x 187.5cm.

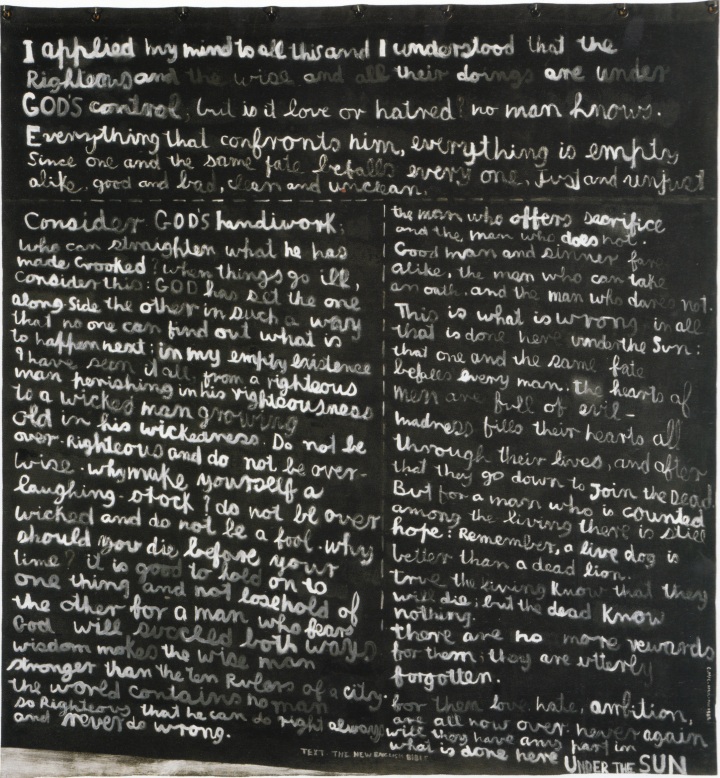

I applied my mind, 1980-82.

Acrylic on unstretched canvas, 195 x 180.5 cm.

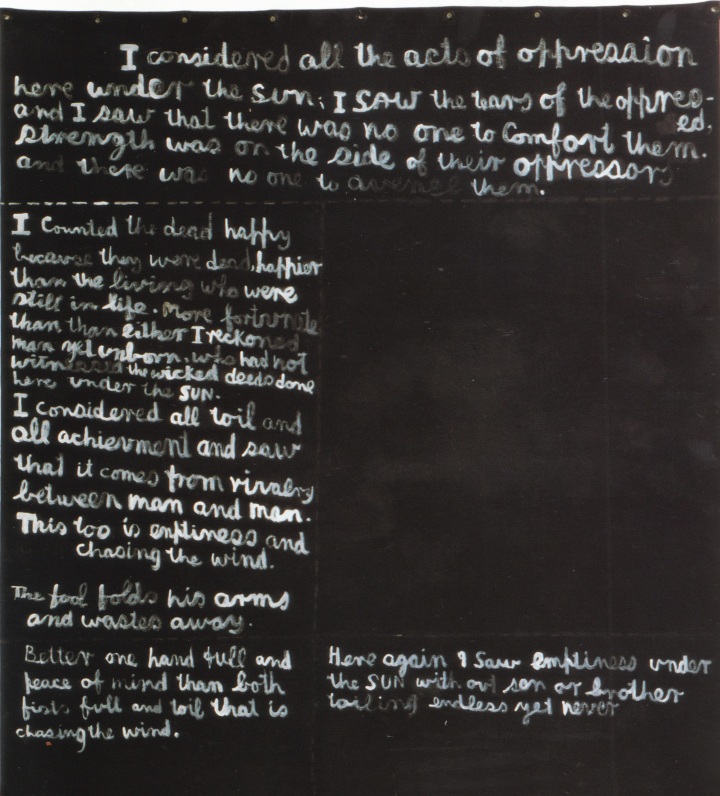

I considered all the acts of oppresssion, 1980-82.

Acrylic on unstretched canvas, 196.4 x 180 cm.

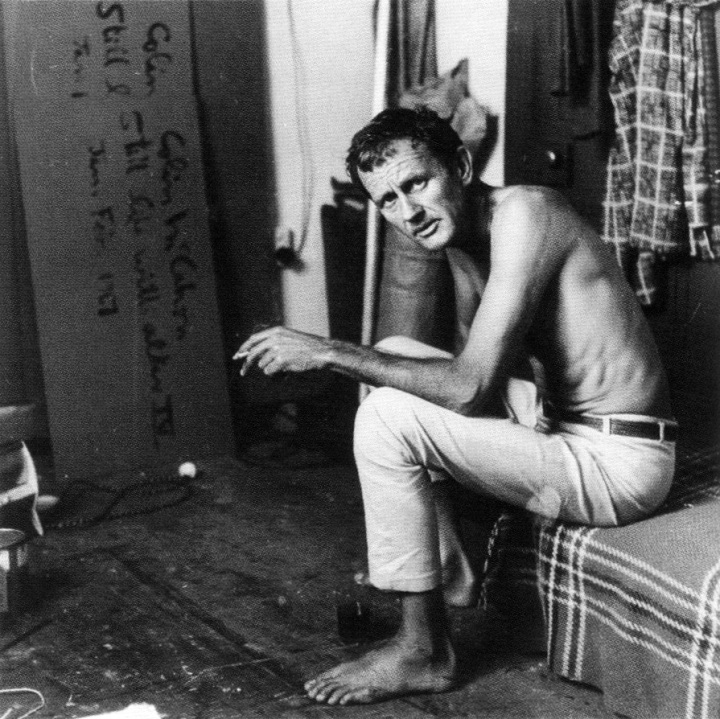

Colin McCahon in the studio at Partridge St. Grey Lynn, Auckland, late 1960s. Courtesy of McCahon Family Archive.

There is a word from the time of the cathedrals: agape, an expression of intense spiritual affinity with the mystery that is ‘to be sharing with another life’. Agape is love, and it can mean ‘the love of another for the sake of God’. More broadly and essentially it is a humble impassioned embrace of something outside the self, in the name of that which we refer to as God, but which also includes the self and is God.

Barry Lopez, Arctic Dreams (London: Picador, 1986)

Driving east from Murupara you can watch the landscape suddenly slip from the grip of the great colonial project. Pastoral plain and pine plantation yield to the primordial, as abruptly as tarseal becomes loose gravel. Up against the wild forcefield of Te Urewera, Britain of the South just gives up.

It is different here, and Colin McCahon knew it. The West’s cataclysm of chance has been through Te Whāiti, Ngāputahi, Ruatāthuna, and Maungapōhatu, as it has every Pacific village. But dispossession here, as with the empires potentials for obliteration, has had but a shadow of it’s success elsewhere in Aotearoa. Te Urewera’s Māori land lies without the gangs of Pākehā farms that now inevitably surround it in other New Zealands, and remains unfazed by their urgent economics. It is as though Tūhoe’s history, their mountain fortress’s inaccessibility, has given them a strength that still sustains. While what now saturates the rest of the country may circle Te Urewera on all sides, it can’t enter. It is as though the land’s life-force is still Māori.

Yet somehow the possibility is betrayed by the way the Māori clearings seem to shrink from what encircles them. The driver too feels diminished by the wild life outside, compared with the passage through a domesticated landscape. Road maps confirm what the view hints. This is the South Pacific, not England. A dark, elemental, forever forest, not to be entered unless you know precisely what you’re doing. Primordial, Gondwanan, shrieking with birds, but unhaunted by the human history that brings time – or landscape – into being. Pacific gods – Papatūānuku, Tāne – have a longer stake in it than Christianity’s one, but the distinction is trivial. This has long been its own place. Brutal news for those who like to call the landscape theirs.

…

Colin McCahon’s eyes needed more than picturesque forest scenery. His peering out of the car window – a constant I gather – was a vital part of his process of looking into ‘New Zealand’, our situation here, and figuring out how to show it to us. His pictures, as he called them, can take the wind out of us, exposing the damage to what another discomforting voice, the cartoonist Michael Leunig, calls our soul’s ‘great, delicate, interconnected ecology’. McCahon was scared by the huge gap in our practical knowledge of ourselves in these ancient islands – dislodging what was here by nature without learning much about it – created by the settler psyche and pieties. ‘Something logical, orderly and beautiful’: these now-celebrated words express his earliest conscious sensing of qualities ‘belonging to the land but not yet to its people. Not yet understood or communicated, not even really invented.’ he meant Pākehā people, in the main, and he decided he would be the inventor. In the process, he created himself an envoy of the power and magic of art such as New Zealand had not experienced before.

Really good art burns itself into your memory and shapes your sense of place. Colin McCahon knew that his encounter with this stretch of country and its diminishing of human projects produced something seminal.

…

Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad’s famed exposé of colonial misdemeanor in Africa, has been label an inveterate piece of racist imperialism. But the darkness Conrad sensed in ‘the primeval forest’, as impenetrable as the darkness in Congo eyes, was not a phenomenon confined to the African arm of the empire. D.H. Lawrence sensed in Australia what Monte Holcroft called ‘the primeval shadow’ here, McCahon painted it, and, inevitably in a culture that is in decolonisation mode and has such a hard eye for tall poppies, some have used that to have a go at him. His inventions have been branded ‘Pathetic Projections: Willfulness in the Wilderness’ by those who detect in them a presumption to be the first speaker in and otherwise ‘silent’ land – a thousand years of Māori settlement notwithstanding.

Yet Colin McCahon’s ‘deeply coded community of signs’ have been compared to Aboriginal songlines. Just as few imagine ecology as being a site for finding answers to the question of whether peace can be a foreground rather than background, landscapes are full of things that most people simply don’t see. Some may look at the landscape and notice the light and the dark, the vulnerabilities and regenerative life forces in the shifting, chancy interplay between culture and nature. The appearance in the mind, even, of a symbol or two. But they’re more likely to move onto another view before the prospect can affect them. Moving left to right, those who would enter his landscapes, must walk along them as Pitjantjtjara and Aranda do their songlines, being cued in to who and where they are, where they came from, and how they relate to what’s going on.

Colin McCahon once said that his landscapes weren’t landscapes. But in interpreting a place through symbol and imagination, they heighten our own perceptions in ways that are rarely permitted by the ordinary process of ‘seeing’. Eyes feeding on the wildness pressing in on him, he came along this road because these dark, primal Aotearoan hills has something to tell, and he’d been asked tell it. Seeking truth in a peculiarly hard place.

…

‘Of the reasons for preserving a fragment of the landscape,’ one of the most insightful readers of landscape has said, ‘the aesthetic is surely the poorest.’ Waikaremoana is particularly beautiful New Zealand scenery, in the midst of what Elsdon Best, writing for tourists, called a ‘picturesque region’. But McCahon was suspicious about beauty of that kind. In a national park, of all places, he seeks to take us out of the world of visibly charged beauty – showing New Zealanders how their preoccupation with scenery, their possessing it ‘preserved’ in reserves, and their dogma that it’s a necessary ingredient of a painted landscape, trapped them in a particular sense of beauty.

‘How to keep… Back Beauty, keep it, beauty, beauty, beauty… from vanishing away?’ asks a poem McCahon was fond of quoting. ‘Give beauty back, beauty, beauty, beauty, back to God, beauty’s self and beauty’s giver.’ We do not own what appears to be most ours, most easily grasped, says Gerald Manley Hopkins, the poet. We have no claim on it – ‘preserving’ it for example – because what is at risk does not belong to us anyway.

What McCahon called his ‘interest in landscape as a symbol of place and also of the human condition’ was central to Hopkins poetry. Hopkins considered the filtering inward of nature to self that he recorded in his contemplations of nature to be so crucial to real understanding that he coined a word for it, a word now used by poets, painters and ecologists alike.

‘Inscape’ is the unfolding of the particularities of nature and the lineage of our encounters with it that put sensory perceptions of a landscape trigger. It’s the antithesis of what strangers’ eyes perceive, ‘unknown and buried away… and yet how near at hand it was if they had eyes to see it’, Hopkins wrote. Inscape distinguishes ‘the Māori landscape’ from the Pākehā one. It allows for both despair and delight at the sight of manuka-covered hillside in the bloom of regeneration. It makes those in New Zealand who are of European descent aware that their colonial project brought an inner landscape, so to speak, across the world, and one which differed at every point from what they found here. It was a kind of self-protective psychological compensation, the Australian Judith Wright has ventured, that made us burn, shoot, chop down and destroy whatever we could, replacing it, ‘if at all with something nearer to the heart’s desire’.

Hopkin’s poetry has been labeled linguistic nationalism for its profound shift from the standard Latin ‘correctness’ of mid-nineteenth century Catholic England to vernacular dialects of Anglo-Saxon folklore and custom. McCahon drew long and sustainingly from Hopkins for much of his painting life, and equivalent nationalism emanates from his landscapes’ candid hostility to the saturating prevalence and power of ‘the picturesque’ in New Zealand landscape painting rules. Inscape, said Hopkins, is ‘the very soul of art’. And just as, without that, he could not describe, in words, the processes and relationships he saw around him, McCahon, similarly, had to devise his own enabling vocabulary of signs.

– you bury your heart, and as it goes deeper into the land

you can only follow. It’s a painful love,

loving a land.

It takes

a

long time.

‘I belong with the wild side of New Zealand’ – The flowing land in Colin McCahon.

Originally written as a commissioned essay for a book to accompany a major exhibition of Colin McCahon.

The exhibition did not eventuate.

Theatre Country: Essays on Landscape and Whenua

Geoff Park

Victoria University Press

2006

___

Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith

Marja Bloem and Martin Browne

Contributions by Rudi Fuchs : William McCahon : Murray Bail : Francis Pound : Steven Miller

Craig Potton Publishing

2002

___

R

Note: This will be the last post on History of Our World.

To those who viewed, commented or supported the website, thank you.

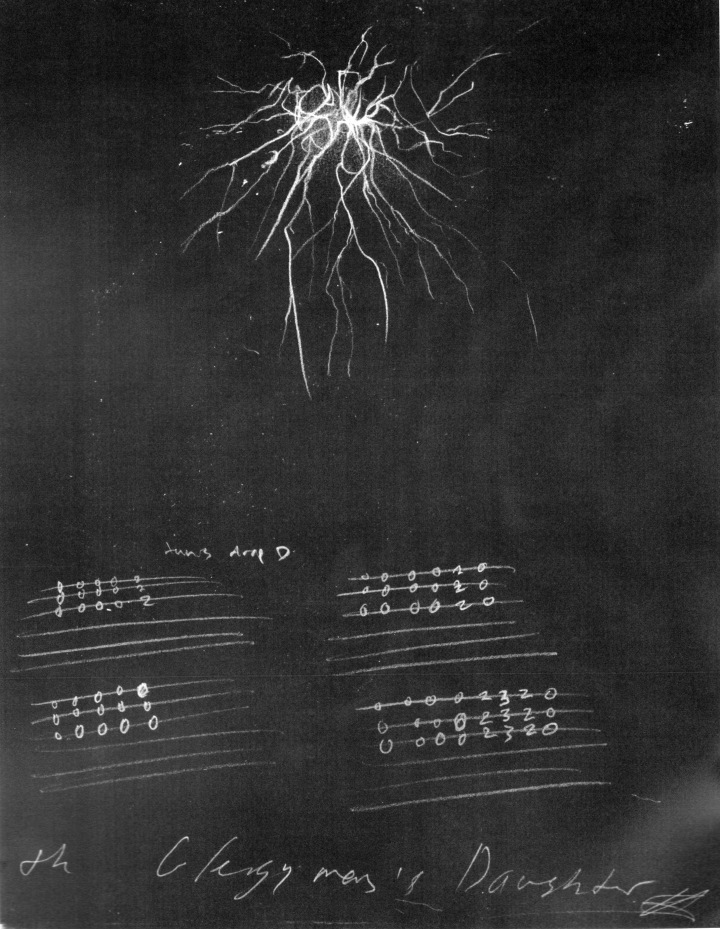

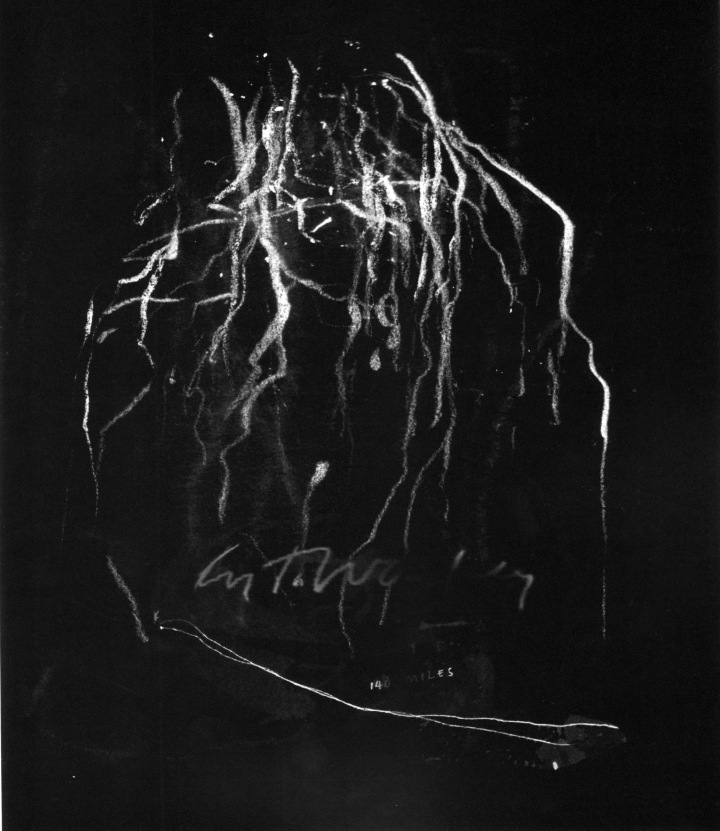

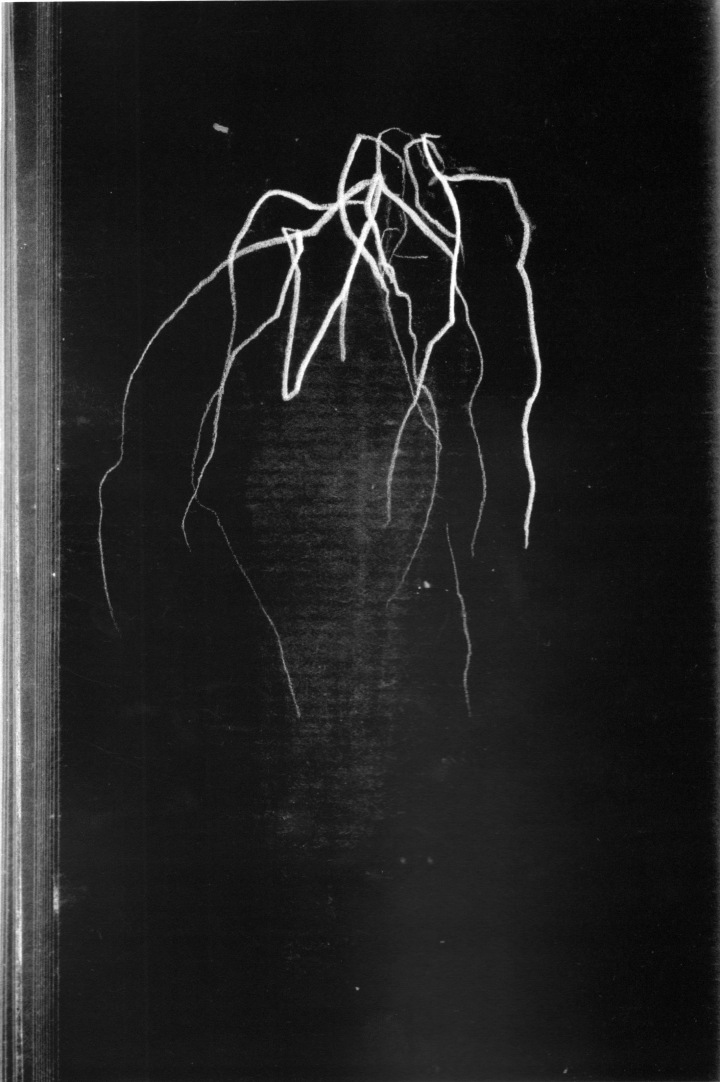

BLACKMETALCYTWÖMBLY / Volumes I, II & III | Andrew McLeod

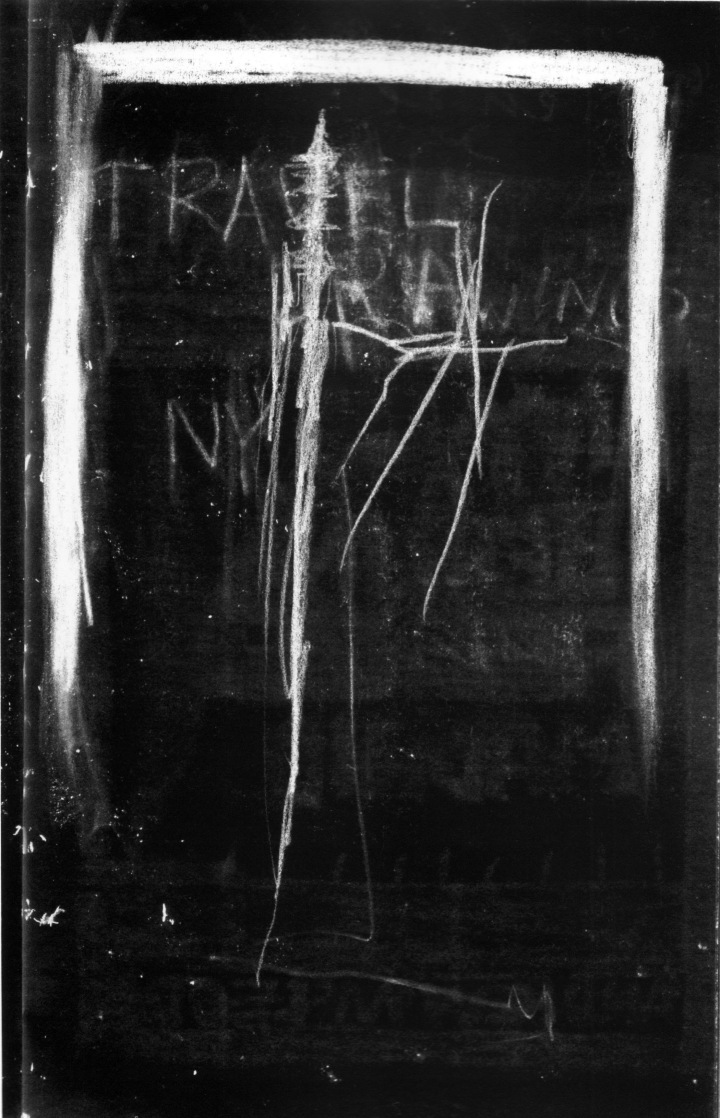

BLACKMETALCYTWÖMBLY / Vol. I, 2010 (unpaginated)

BLACKMETALCYTWÖMBLY / Volume II, 2010 (unpaginated)

BLACKMETALCYTWÖMBLY / Volume III, 2010 (unpaginated)

___

BLACKMETALCYTWÖMBLY / Volumes I, II & III

Andrew McLeod

2010

___

R

Do You Know What I Mean | Juergen Teller

All images; Ed in Japan, 2005/2006; originally published as Ed in Japan (Paris: Purple publications, 2006).

…It was unusual and powerful. It was clear that he was putting people in some kind of danger. There was no concern for classical beauty, but it took people somewhere else…

When Juergen starts to shoot he shoots constantly. It’s like a form of intrusion. You almost feel trapped. That’s how he manages to capture those completely uncontrolled moments because he literally traps you in his camera…

That’s how he gets those intimate moments, those unconscious movements of the body and mind. He doesn’t give you the time to organize your own mise en scène. He doesn’t give you time to think about what you are going to do. He anticipates the slightest of your movements, the slightest of your inner thoughts, and that’s how he manages to capture this incredible truth in bodies, in faces. He tries to avoid any conscious expression…

Isabelle Huppert

___

Do You Know What I Mean

Juergen Teller : Marie Darrieussecq : Isabelle Huppert

Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain / Thames & Hudson

2006

___

R

Complete Works | Vincent Van Duysen

Photo essay by Alberto Piovano (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

Photo essay by Alberto Piovano (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

M Residence, Mallorca, Spain, 1996-1997 (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

VL Residence, Bruges, Belgium, 1999-2000 (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

DC Residence, Waasmunster, Belguim, 1998-2001 (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

Capco Offices, Antwerp, Belgium / New York, USA, 1999-2001 (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

Copyright Bookshop, Antwerp, Belgium, 2000-2001 (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

VVD Residence, Dendermonde, Belgium, 1998-2003 (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

Desk and Chair for Bulo, 2004 (Photography by Alberto Piovano)

Neutra Outdoor Collection for Tribù, 2008 (Photography by Alberto Piovano)

On Vincent

Vincent’s work is human;

it possesses many qualities

that we value in people.

It is calm yet determined.

It is reliable yet surprising.

It is sensual, but discreetly so.

It is sober yet spirited.

In other words, it is like a good friend,

like Vincent himself.

Ann Demeulemeester and Patrick Robyn

_

‘Verwechseln Sie bitte nicht das Einfache mit dem Simplen’

(Don’t confuse minimal with simple)

Mies van der Rohe

___

Complete Works

Vincent Van Duysen : Ilse Crawford : Marc Dubois

Thames & Hudson

2010

___

R

Maison Martin Margiela

Store in Los Angeles, Beverly Hills _ Opened on September 5th, 2007 _ Images of architectural details such as doors, stucco and moldings from Maison Martin Margiela’s former premises in Paris are are printed on transparent films

A/W 1990-91 _ Women’s show _ backstage

S/S 1990 _ Tabi boots with hand-tagged graffiti

A/W 2000-01 _ Cooperation magazine, oversized collection feature and snap shots of looks

1999 – Door sign, Boulevard Saint-Denis (headquarters of the Maison from 1990 to 1994)

A/W 2008-09 _ Women’s show, backstage

Headquarters, Paris _ Special installation in the rue Saint-Maur showroom

October 2008 _ Special and limited edition Tabi-boot shaped candle, Sent as a gift to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Maison Martin Margiela

Headquarters, Paris _ Dress forms in Martin Margiela’s studio, Boulevard Saint-Denis (headquarters of the Maison from 1990 to 1994)

S/S 2005 _ Arena Homme+ _ Line 0 _ Peter Doherty wearing a shirt printed with lipstick kisses

S/S 2007 _ Line 0 _ Invitation to the presentation of the ‘Artisanal’ collection, in the form of white embroidery on starched white cotton. It has maintained this form for every season since S/S 2006

A staff member on the stairs at the Paris headquarters, rue Saint-Maur

S/S 1998 _ View on colour _ Interview

Headquarters, Paris _ Workshop in the Maison Martin Margiela rue Saint-Maur offices

Store in Osaka _ opened on August 28th, 2003 _ Invitation and shoe display

Headquarters, Paris _ Men’s commerical showroom _ The custom made trunk and white tailors dummy’s identify the Line 14 concept: A classic and timeless wardrobe for men

The past is what binds us,

The future leads us.

___

Maison Martin Margiela

Rizzoli

2009

___

The Cult of Invisibility by Lucian James

R

What Remains | Sally Mann

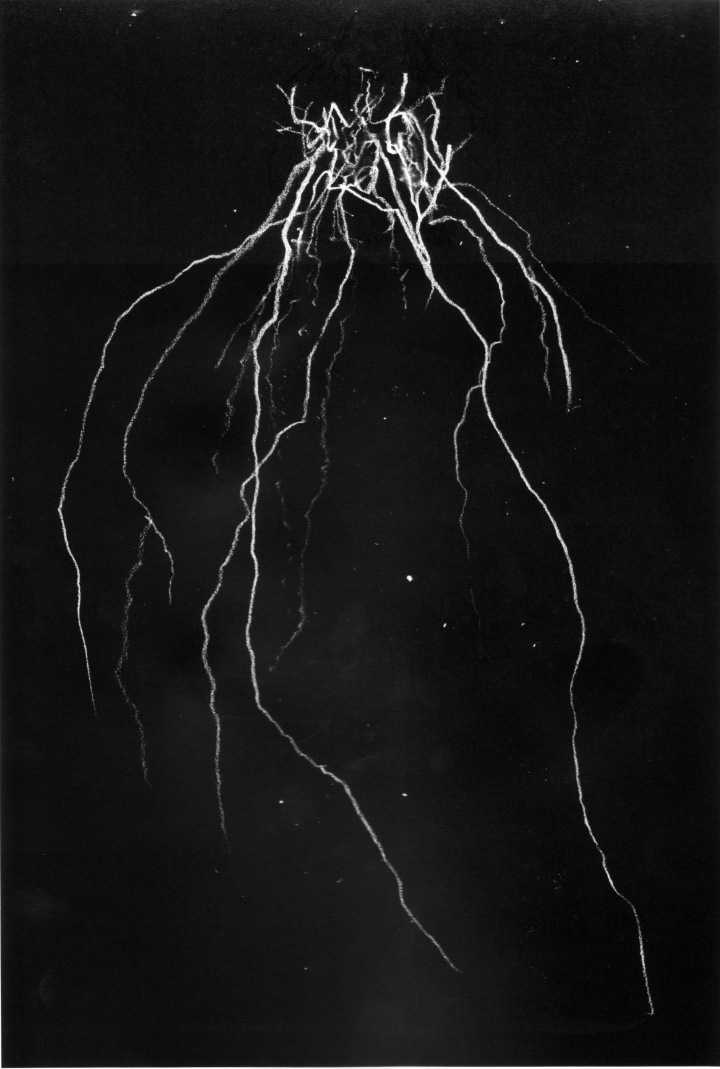

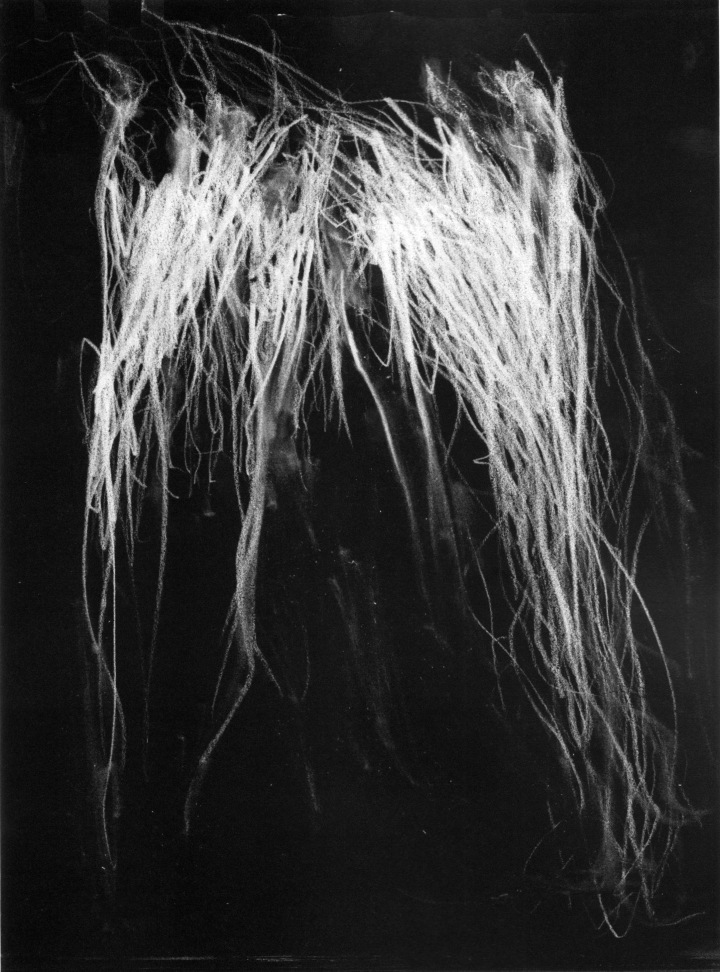

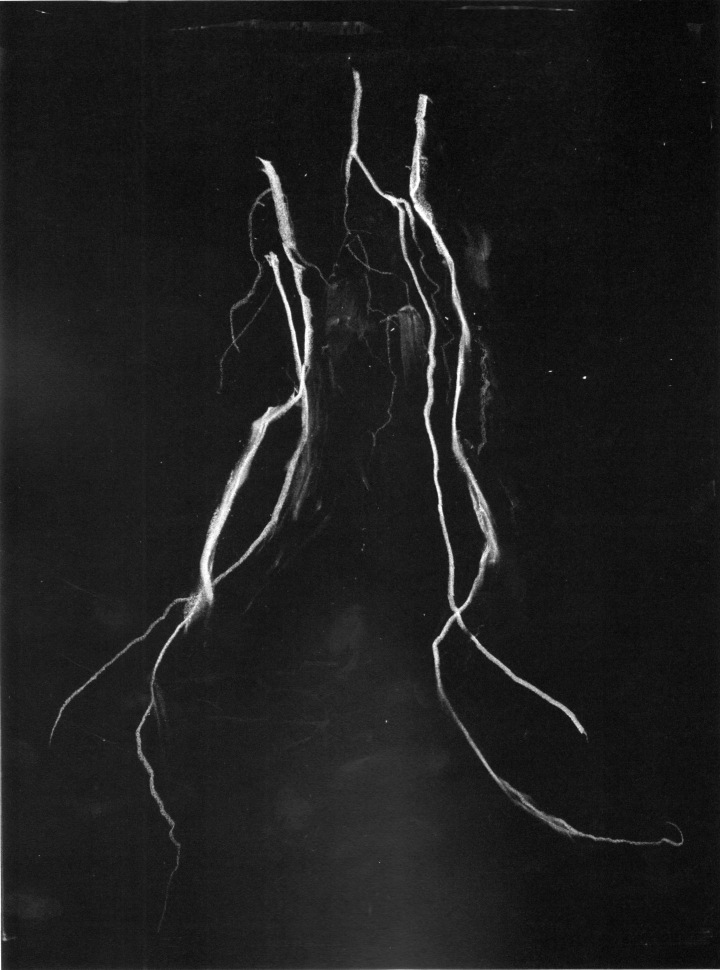

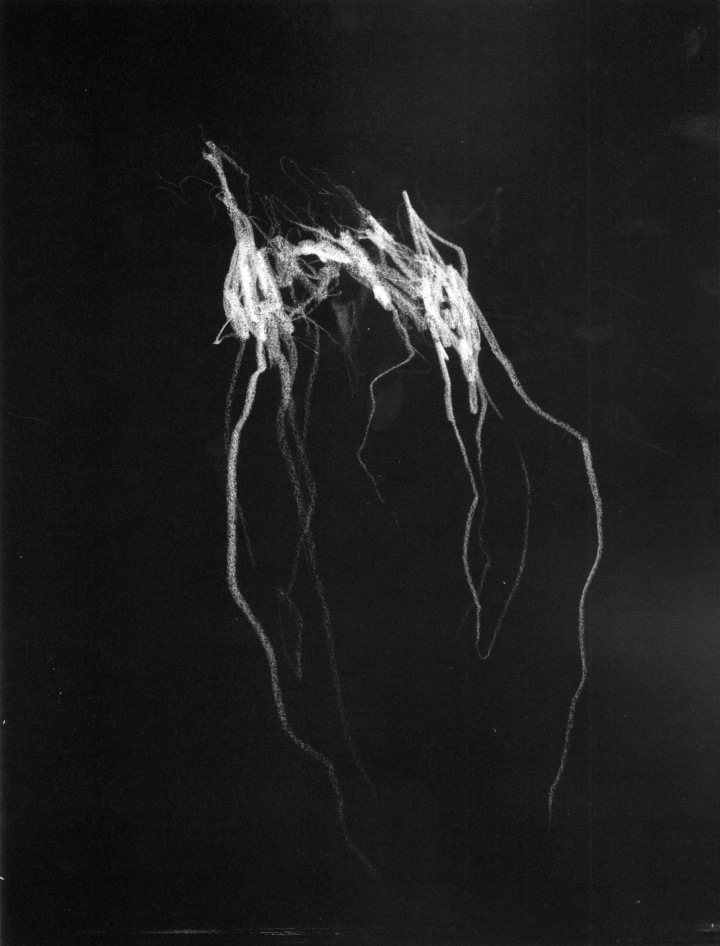

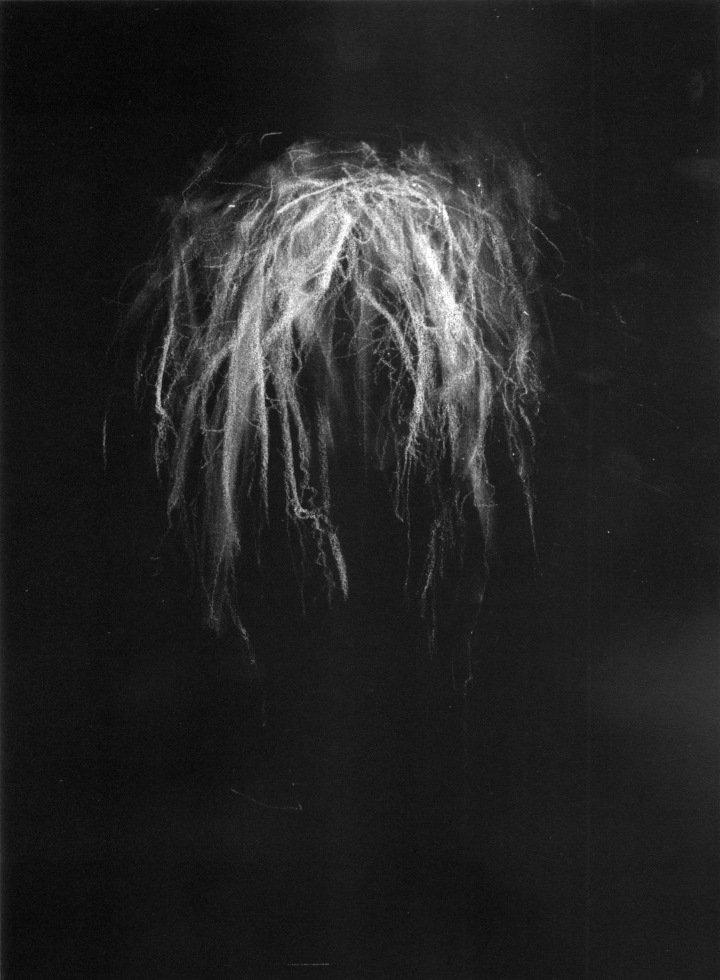

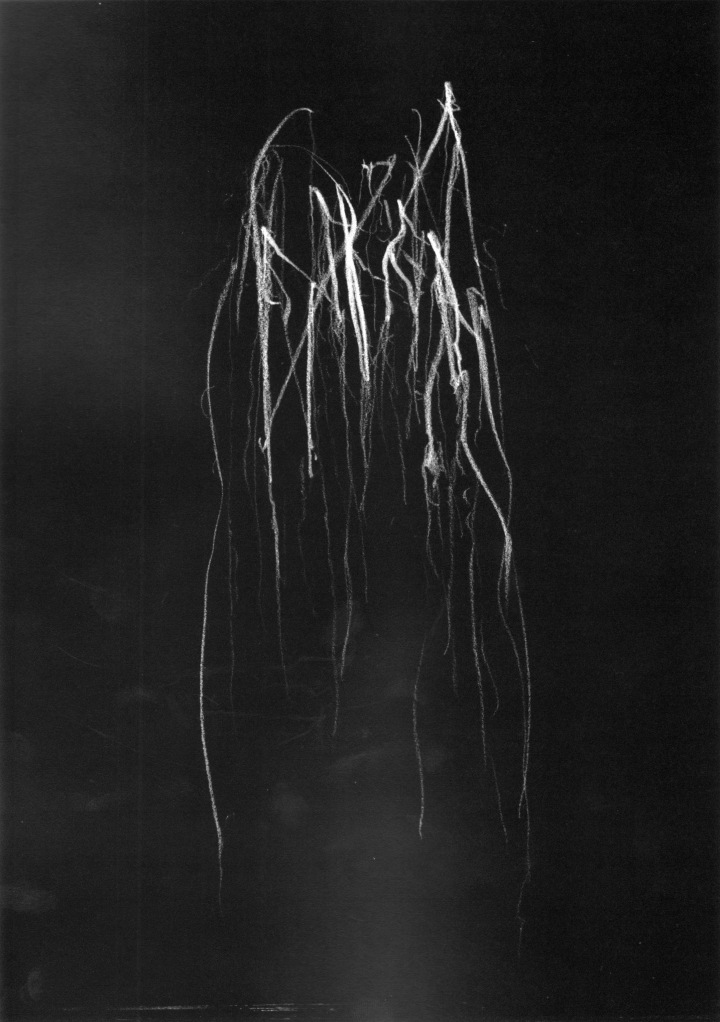

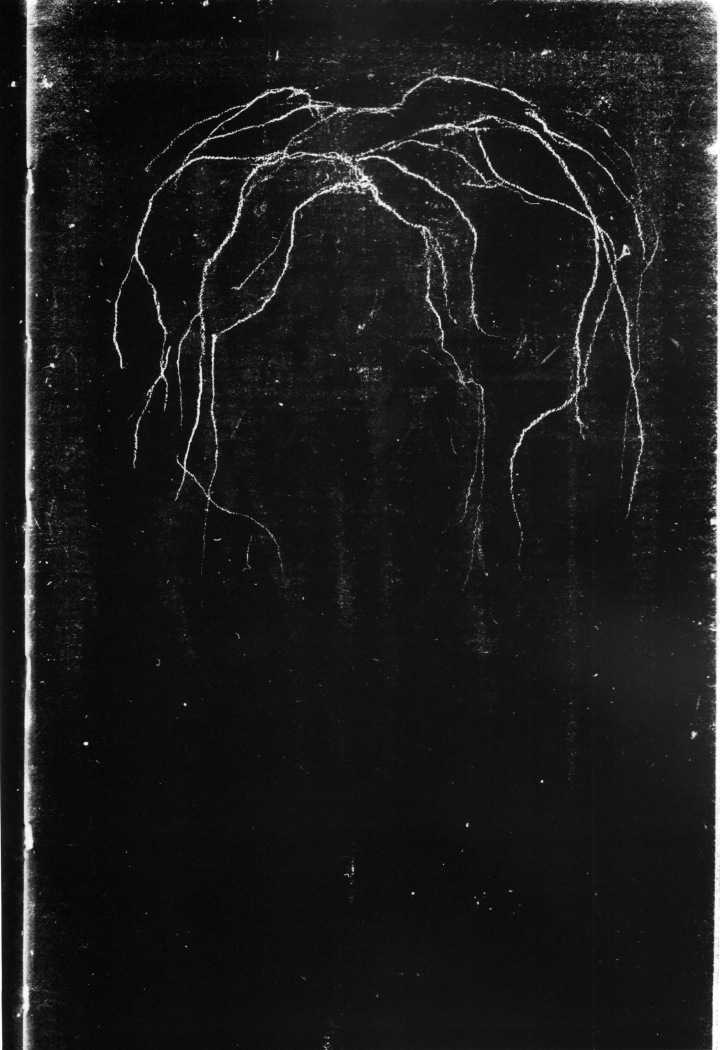

Untitled (Matter Lent)

All things summon us to death;

Nature, almost envious of the good she has given us,

Tell us often and gives us notice that she cannot

For long allow us that scrap of matter she has lent…

She has need of it for other forms,

She claims it back for other works.

Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (1627-1704), “On Death, a Sermon”

Untitled (Matter Lent)

Untitled (Matter Lent)

Untitled (Matter Lent)

Untitled (Matter Lent)

Untitled (Matter Lent)

Untitled (Matter Lent)

Untitled (Matter Lent)

Untitled (Matter Lent)

Untitled (Matter Lent)

___

…He must have ditched the shotgun because by the time he approached the house he only had the pistols. Ducking behind a tree, he put one of them to his head. His shot was tinnily distinguishable from the rifle shots of the police who had appeared at the last moment. He fell among the stumps and bracken, just a kid after all, my son’s age, bled out in the milky winter light.

Untitled (December 8, 2000)

Untitled (December 8, 2000)

Untitled (December 8, 2000)

Untitled (December 8, 2000)

___

Pensive on her dead gazing I heard the Mother of All,

Desperate on the torn bodies, on the forms covering the battlefields gazing,

(As the last gun ceased, but the scent of the powder-smoke linger’d,)

As she call’d to her earth with mournful voice while she stalk’d,

Absorb the well O my earth, she cried, I charge you lose not my sons,

lose not an atom

And you streams absorb them well, taking their dear blood,

And you local spots, and you airs that swim above lightly impalpable,

And all you essences of soil and growth, and you my rivers’ depths,

And you mountain sides, and the woods where my dear children’s blood

trickling redden’d

Untitled (Antietam)

And you trees down in your roots to bequeath to all future trees,

My dead absorb or South or North – my young men’s bodies absorb,

and their precious blood,

Which holding in trust for me faithfully back again give me many a year hence,

In unseen essence and odor of surface and grass, centuries hence,

In blowing airs from the fields back again give me my darlings,

give my immortal heroes,

Exhale me them centuries hence, breathe me their breath, let not an atom be lost,

O years and graves! O air and soil! O my dead, an aroma sweet!

Exhale them perennial sweet death, years, centuries hence.

Walt Whitman, from Leaves of Grass

Untitled (Antietam)

Untitled (Antietam)

Untitled (Antietam)

Untitled (Antietam)

Untitled (Antietam)

Untitled (Antietam)

Untitled (Antietam)

When the land subsumes the dead, they become the rich body of the earth, the dark matter of creation. As I walk the fields of this farm, beneath my feet shift the bones of incalculable bodies; death is the sculptor of the ravishing landscape, the terrible mother, the damp creator of life, by whom we are one day devoured.

___

What Remains

Sally Mann

Bulfinch Press

2003

___

R

The Matter of Time | Richard Serra

Forming of the plates for The Matter of Time at Pickhan Umformtechnik, Siegen, Germany

Serra (center) and others installing One Ton Prop (House of Cards) at the Museum of Art, RISD, Providence, 1969

Robert Smithson and Richard Serra, 1970

Frames from Hand Catching Lead, 1968

Tilted Arc, 1981. Weatherproof steel, cylindrical section tilted into the ground, 12′ x 120′ (3.66 x 36.58 m), plate thickness 2½” (6.5 cm). General Services Administration, Washington D.C. Installed at Federal Plaza, New York, 1981-89; destroyed by the United States Government, 1989.

Installation of To Encircle Base Plate Hexagram, Right Angles Inverted at 183rd Street and Webster Avenue, Bronx, New York, 1970.

Shift, 1970-72. Concrete, six sections; section one: 5′ x 240′ (1.52 x 73.15 m); section two: 5′ x 150′ (1.52 x 45.72 m); section three: 5′ x 120′ (1.52 x 36.57 m); section four: 5′ x 105′ (1.52 x 32 m); section five 5′ x 110′ (1.52 x 33.52 m); section six 5′ x 90′ (1.52 x 27.43 m); section thickness: 8″ (20 cm). Installed in King City, Ontario, Canada.

Serpentine, 1993. Weatherproof steel, two units, each comprised of two conical sections, each section: 13’2″ x 52′ (4 x 15.85 m); length overall: 104′ (31.7 m): plate thickness 2″ (5 cm). Collection of Frances and John Bowes, Sonoma, California.

Torqued Ellipse II, 1996. Weatherproof steel, 12′ 29′ x 20’5″ (3.66 x 8.83 x 6.22 m); plate thickness: 2″ (5 cm). Dia Art Foundation. Gift of Leonard and Louise Riggio.

Afangar (Stations, Stops on the Road, to Stop and Look: Forward and Back, to Take It All In), 1990. Basalt, eighteen stones; nine: 9’10” x 1’9″ x 1’9″ (3 x .55 x .55 m): nine: 13’1½” x 1’9″ x 1’9″ (4 x .55 x .55 m). City of Reykjavik, Iceland. Installed Videy Island, Reykjavik Harbor.

Richard Serra, photographed by Robert Frank, 2002

The List:

To roll, to crease, to fold, to store, to bend, to shorten, to twist,

to dapple, to crumple, to shave, to tear, to chip, to split, to cut,

to sever, to drop, to remove, to simplify, to differ, to disarrange,

to open, to mix, to splash, to knot, to spell, to droop, to flow,

to curve, to lift, to inlay, to impress, to fire, to flood, to smear,

to rotate, to swirl, to support, to hook, to suspend, to spread,

to hang, to collect –

of tension, of gravity, of entropy, of nature, of grouping,

of layering, of felting –

to grasp, to tighten, to bundle, to heap, to gather, to scatter,

to arrange, to repair, to discard, to pair, to distribute, to surfeit,

to complement, to enclose, to surround, to encircle, to hide,

to cover, to wrap, to dig, to tie, to bind, to weave, to join,

to match to laminate, to bond, to hinge, to mark, to expand,

to dilute, to light, to modulate, to distill –

of waves, of electromagnetism, of inertia, of ionization,

of polarization, of refraction, of simultaneity, of tides, of reflection,

of equilibrium, of symmetry, of friction –

to stretch, to bounce, to ease, to spray, to systematize,

to refer, to force –

of mapping, of location, of context, of time, of carbonization –

to continue.

The “Verb list” established a logic whereby the process that constituted a sculpture remains transparent. Anyone can reconstruct the process of the making by viewing the residue.

The sculptures resulting from the “Verb list” introduced two aspects of time: the condensed time of their making and the durational time of their viewing.

Both tasks and materials were ordinary. I was tearing lead in place, lifting rubber in place, rolling and propping lead sheets, and melting lead and splashing it against the juncture between wall and floor. The activities were experimental and playful. It wasn’t the question of how to accomplish this or that, nor was it the question of making it up as I went along: it was rather a free-floating combination of both.

I cannot overemphasize the need for play, for in play you don’t extract yourself from your activity. In order to invent I felt it necessary to make art a practice of affirmative play or conceptual experimentation. The ambiguity of play and its transitional character provides suspension of belief whereby a shift in direction is possible when faced with a complexity that you don’t understand. Free from skepticism, play relinquishes control. Play allows one to accept discontinuities and continuities; it also allows one to happen upon solutions or invent them. However, even in play the task must be carried out with conviction. It’s how we do what we do that confers meaning on what we have done.

– Richard Serra (excerpt from Questions, Contradictions, Solutions, 2004)

___

The Matter of Time

Richard Serra : Hal Foster : Carmen Giménez : Kate D. Nesin

Steidl

2005

(This publication accompanies the installation of The Matter of Time at the Guggenheim Bilbao. Curated and organized by Carmen Giménez. Sponsored by Arcelor)

___

R

Jannis Kounellis

Senza Titolo. 1975. Studio d’Arte Contemporanea, Rome

Senza Titolo, 1993. Palazzo Fabroni, Pistoia

Senza Titolo, 1983. Ateneumin Taidemuseo, Helsinki

Senza Titolo, 1969. Modern Art Agency, Naples

Senza Titolo, 1980. Galleria Mario Pieroni, Rome

Senza Titolo, 1994. Jean Bernier Gallery, Athens

Senza Titolo, 1999. Inglesia de San Augustin, Mexico City

Senza Titolo, 1976. Galleria Salvatore Ala, Milan

Senza Titolo, 2003. Torrione Passari, Molfetta

Senza Titolo, 1980. Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Ghent

Senza Titolo, 2000. Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, Valmontone

Senza Titolo, 1996. Piazza del Plebiscito, Naples

Senza Titolo, 2006. Halle Verrière, Meisenthal

Senza Titolo, 2005. MADRE – Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina, Naples

“It’s not for this form or another, but for creating the possibility of life, no? An attempt to open something outside these walls of convention. With our work we try to open an unconventional road to language, because language is stereotyped and in using language it constantly stereotypes itself. Our task is this: to find the means of opening more ways to communicate. This is what I believe.” – Jannis Kounellis.

Born in Piraeus in 1936 but living in Rome since the mid-fifties, Jannis Kounellis is considered a seminal contributor to the radically and internationally influential Arte Povera group. Literally meaning ‘Poor Art’, this began as an anti-elitist movement promoting a new openness towards artistic production, characterised by the use of antithetical materials such as sacks, beans, metal, coal, coffee, wool and gas. These unusual materials help the artist to manifest visceral “pictures” conveying a sense of the forgotten forces of an archaic world. Often epic in scale, Kounellis’s work possesses a grandeur that reflects his frequent choice of themes and ideas from the past and particularly from Ancient Greece.

Kounellis began his career as a painter, inspired in part by the work of American abstract artists of the 1950s. However, during the 1960s he abandoned traditional painting in favour of a host of everyday materials with which he created sculptures and installations, using wool, coal, iron, stones, earth, wood and even, controversially, live animals. As a result ordinary objects and natural matter hold a poetic directness and immediacy for Kounellis who is seeking to establish more concrete communication between the viewer and the artwork.

___

Jannis Kounellis

Angela Schneider: Anke Daemgen: Marc Scheps: Melanie Wilkin: Elisabeth Campolongo

Hatje Cantz

2008

___

B

9 comments