A Question of Faith | Colin McCahon

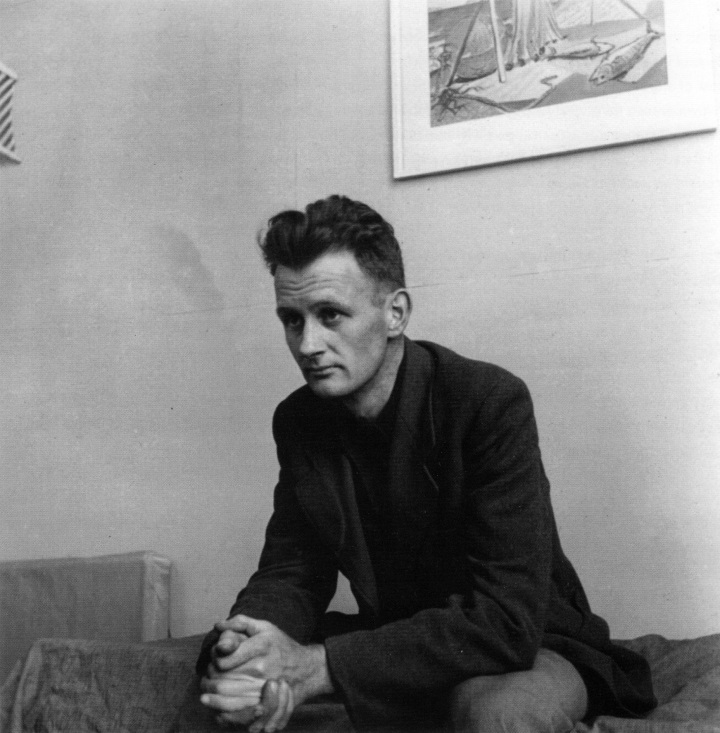

Colin McCahon, c. 1950. Courtesy of the Doris Lusk Estate.

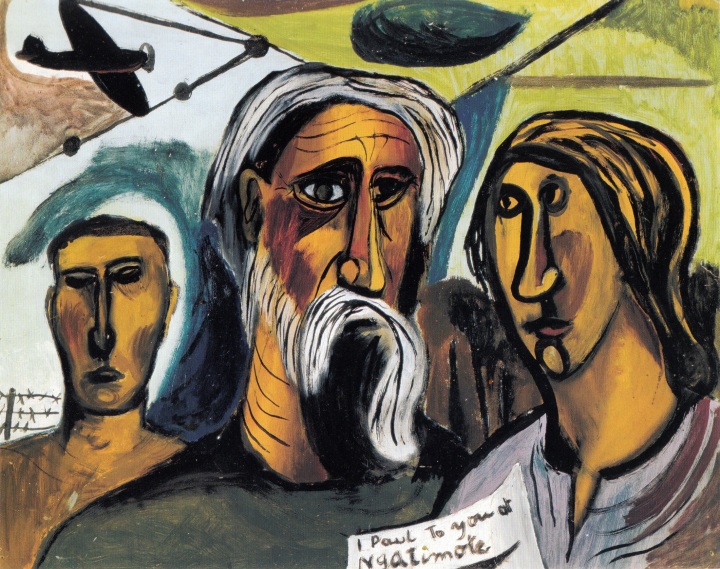

I Paul to you at Ngatimote, 1946.

Oil on cardboard, 50.5 x 63.5 cm.

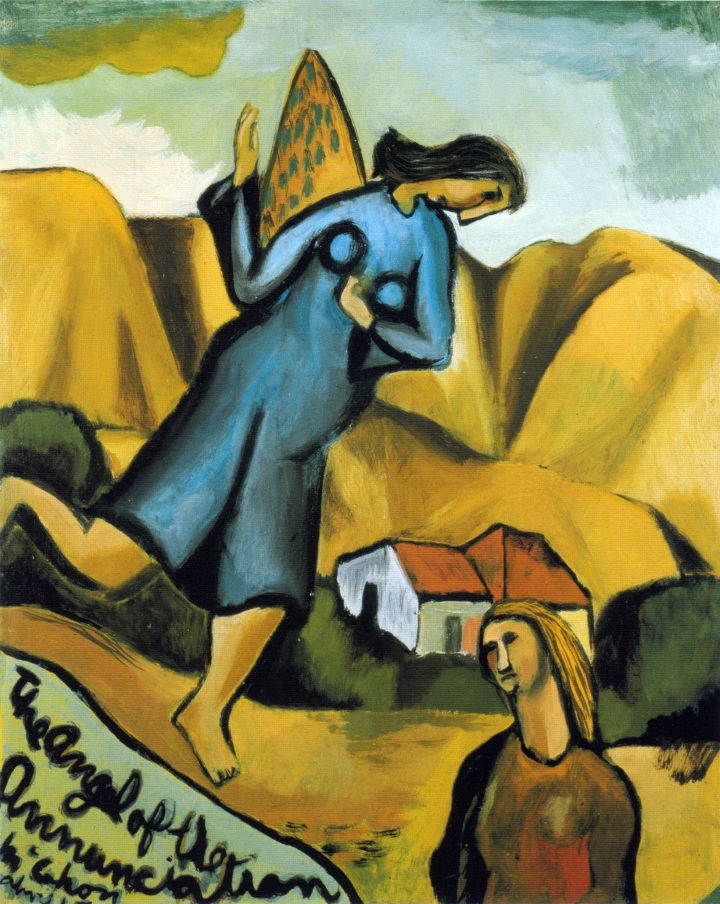

The Angel of the Annunciation, 1947.

Oil on cardboard, 63.5 x 51.2 cm.

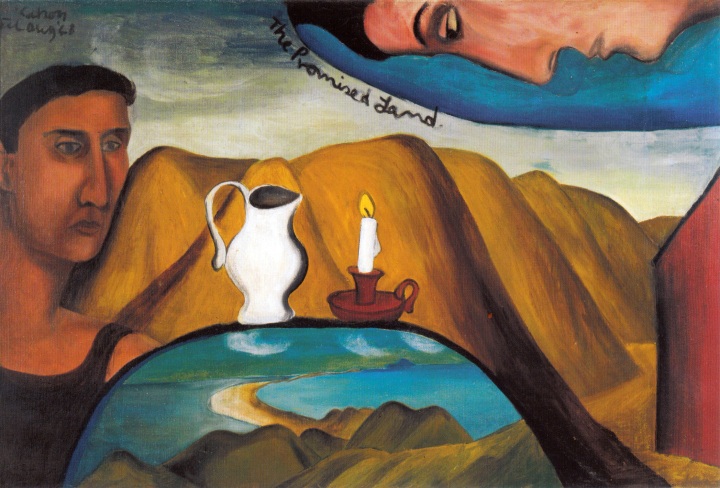

The Promised Land, 1948.

Oil on canvas, 92 x 137 cm.

The King of the Jews, 1947.

Oil on cardboard mounted on hardboard, 63.6 x 52 cm.

North Otago Landscape, 1951.

Oil on canvas on board, 51.5 x 66.2 cm.

Six days in Nelson and Canterbury, 1950.

Oil on canvas laid on board, 88.5 x 116.5 cm.

Cross, 1959.

Enamel on hardboard, 121.9 x 76.2 cm.

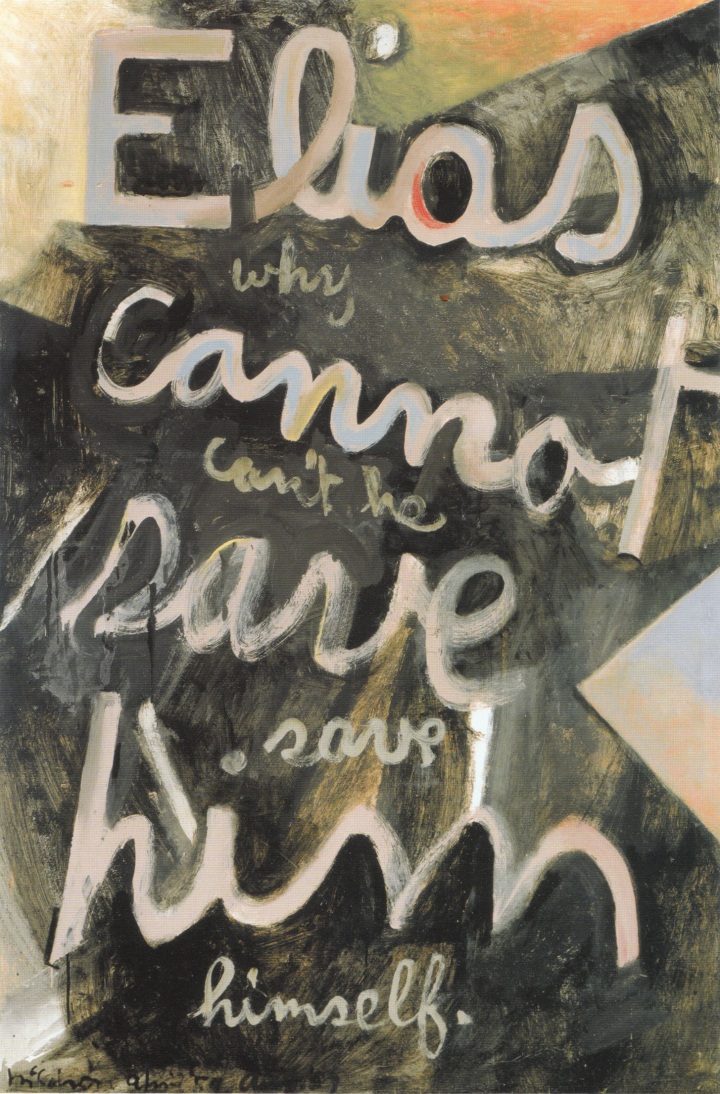

Elias: why can’t He save Himself (Elias series), 1959.

Enamel and sawdust on hardboard, 147.5 x 100 cm.

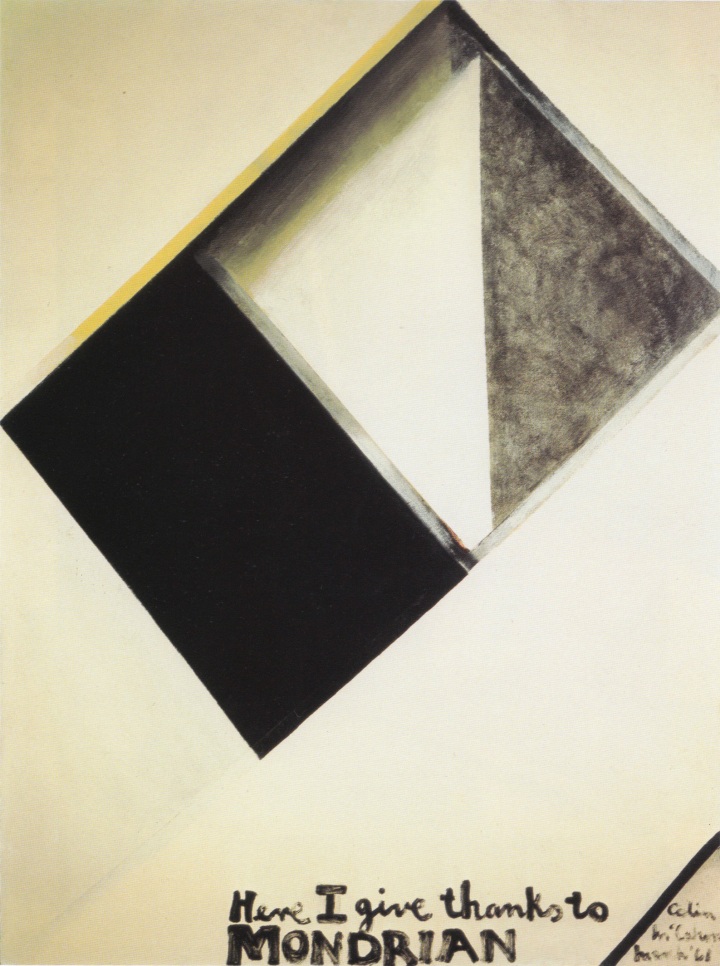

Here I give thanks to Mondrian, 1961.

Enamel on hardboard, 121.8 x 91.4 cm.

![095 Waterfall [one panel from a polytych], 1964](https://historyofourworld.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/095-waterfall-one-panel-from-a-polytych-1964.jpg?w=720&h=1701)

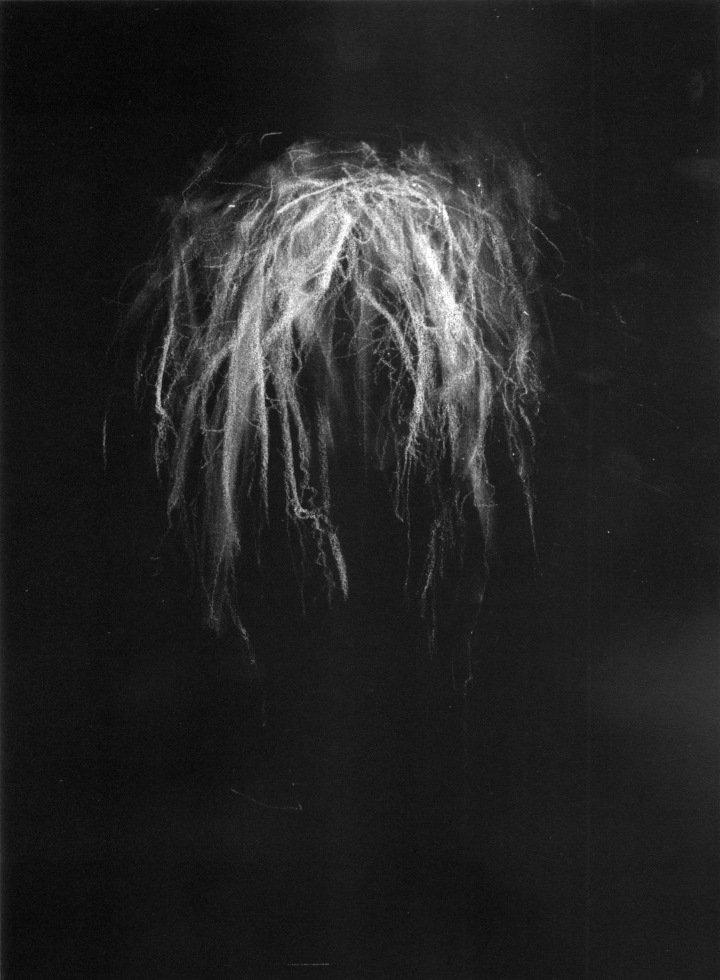

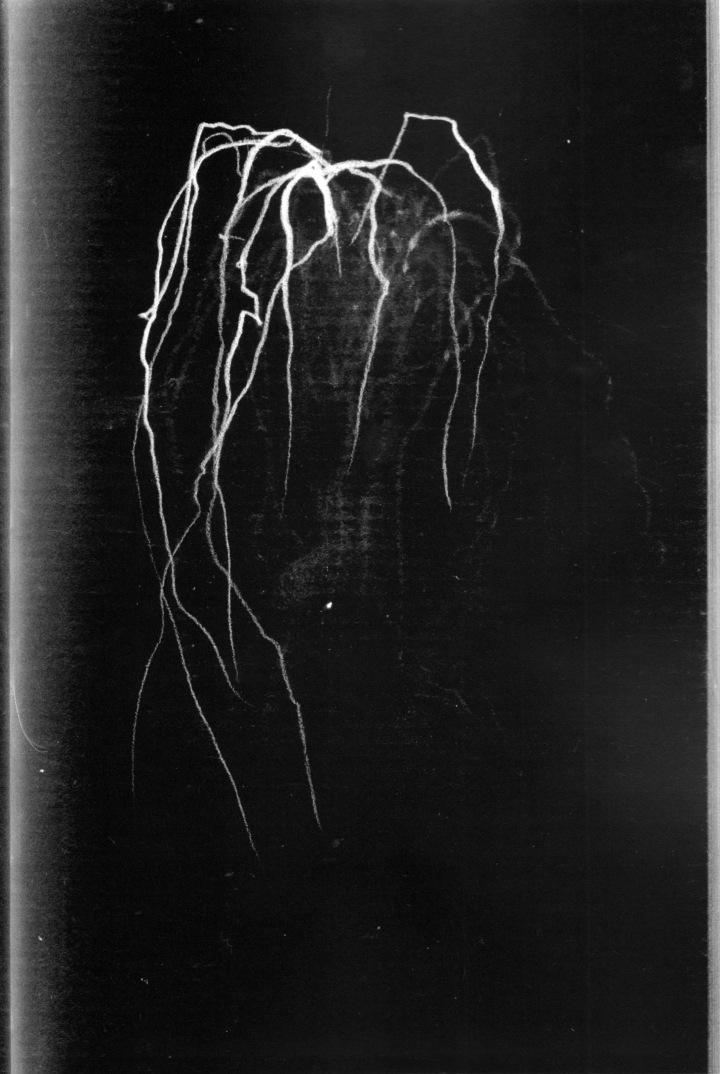

Waterfall [one panel from a polytych], 1964.

Enamel on plywood panel, 212.7 x 90.5 cm.

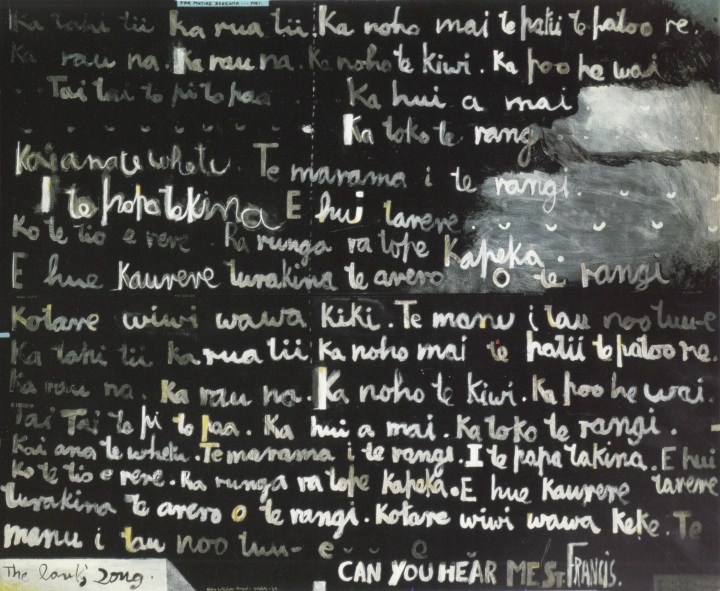

The Lark’s Song (a poem by Matire Kereama), 1969.

Acrylic on two wooden doors, overall 162.6 x 198 cm.

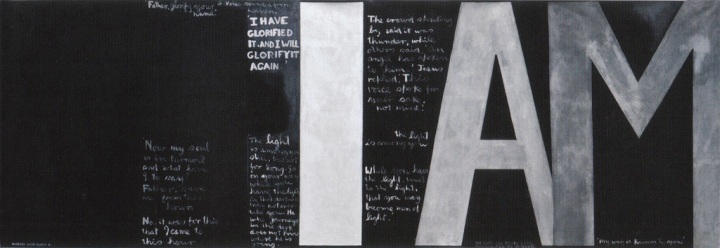

Victory over Death 2, 1970.

Acrylic on unstretched canvas, 207.5 x 597.7 cm.

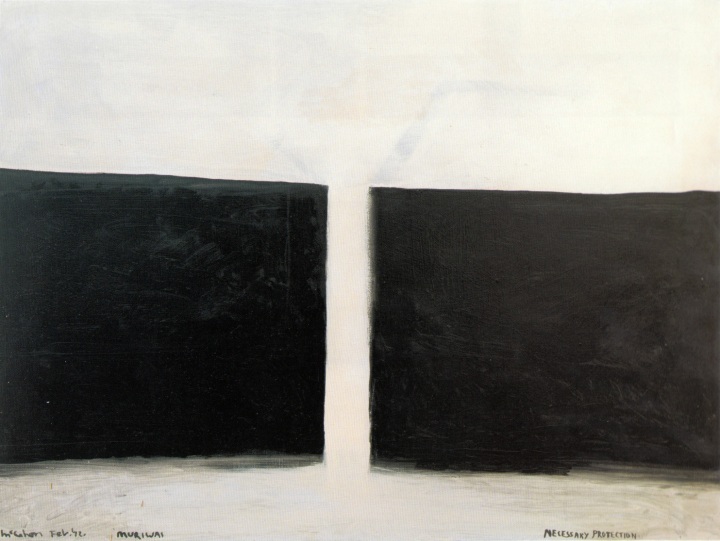

Muriwai. Necessary Protection, 1972.

Acrylic on hardboard, 60.8 x 81.2 cm.

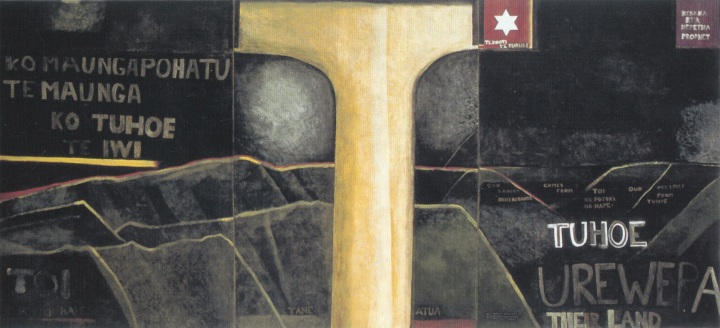

Urewera Mural, 1975.

Acrylic on three unstretched canvases, overall 255 x 544.5 cm.

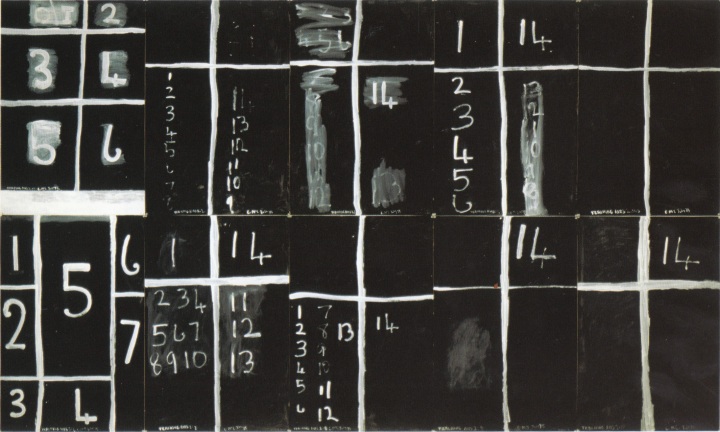

Teaching Aids 2 (July), 1975.

Acrylic on Steinbach paper, 10 sheets, each 109.2 x 72.8 cm, overall size 218.4 x 364 cm.

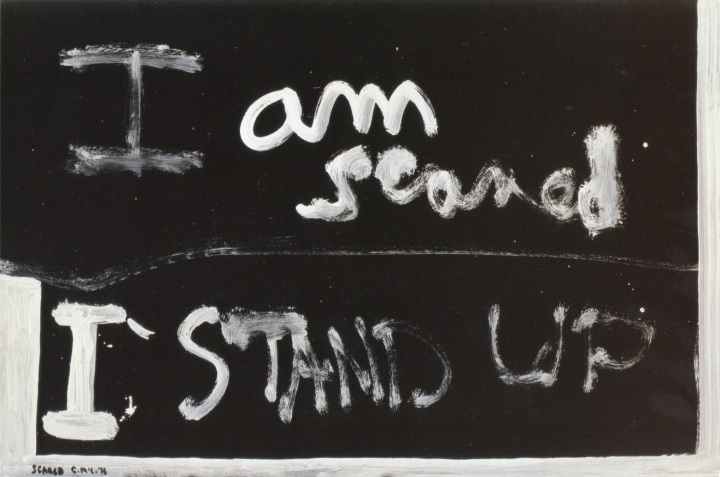

Scared, 1976.

Acrylic on Steinbach paper, 71.5 x 107 cm.

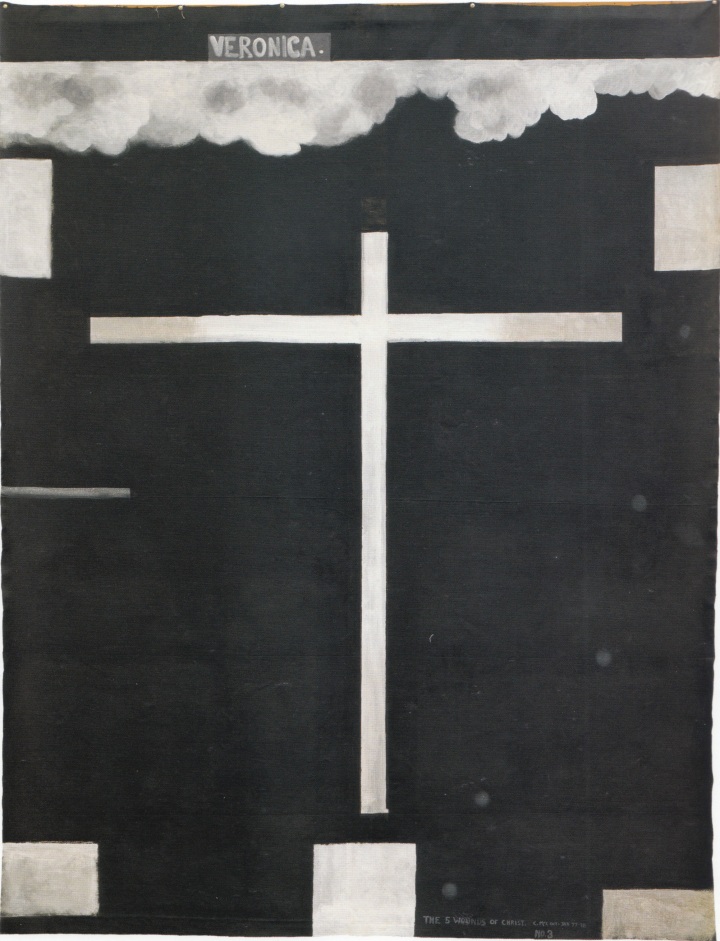

The 5 Wounds of Christ no. 3: Veronica, 1977-78.

Acrylic on unstretched canvas, 242 x 187.5cm.

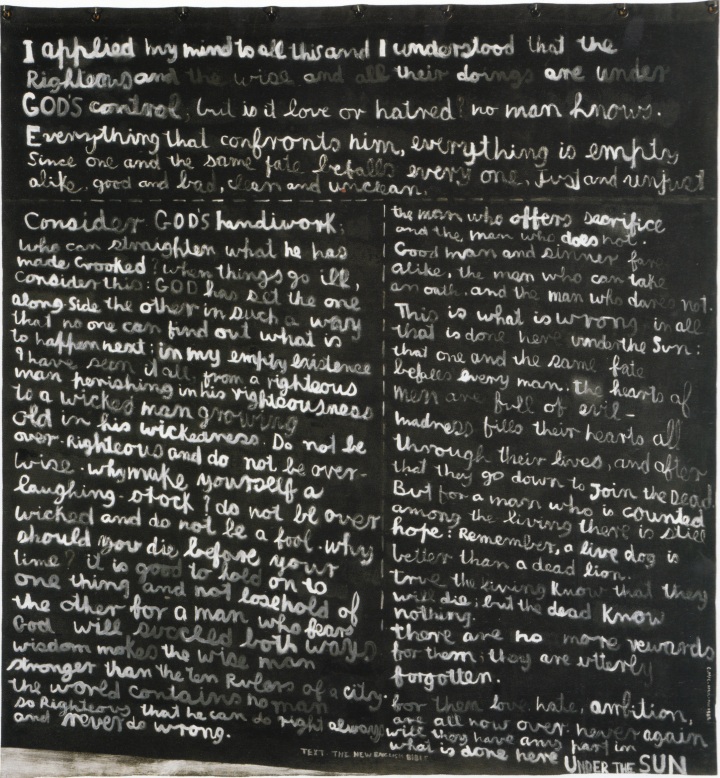

I applied my mind, 1980-82.

Acrylic on unstretched canvas, 195 x 180.5 cm.

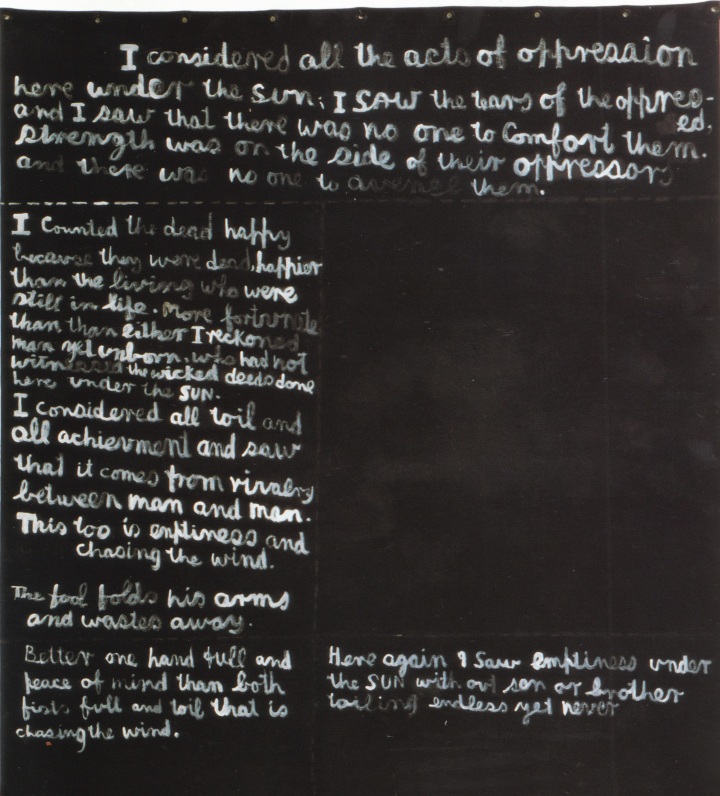

I considered all the acts of oppresssion, 1980-82.

Acrylic on unstretched canvas, 196.4 x 180 cm.

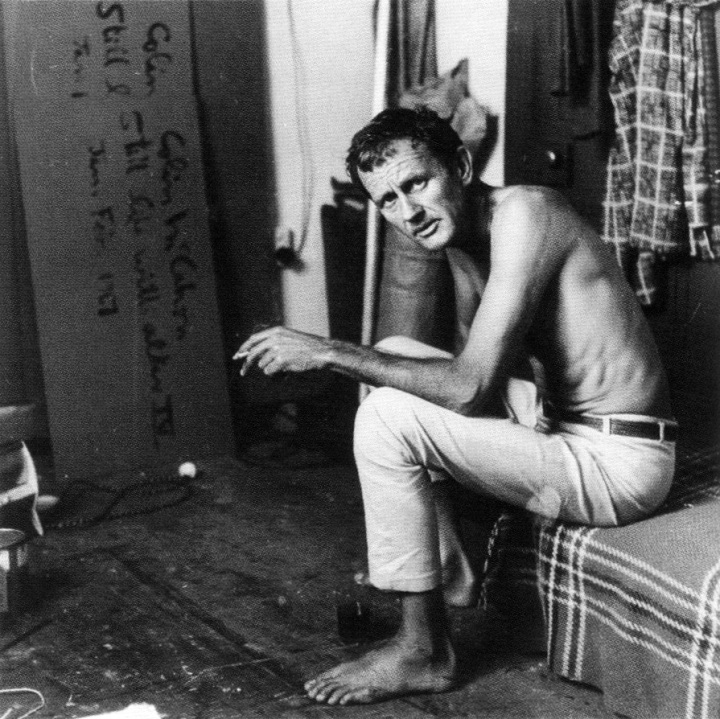

Colin McCahon in the studio at Partridge St. Grey Lynn, Auckland, late 1960s. Courtesy of McCahon Family Archive.

There is a word from the time of the cathedrals: agape, an expression of intense spiritual affinity with the mystery that is ‘to be sharing with another life’. Agape is love, and it can mean ‘the love of another for the sake of God’. More broadly and essentially it is a humble impassioned embrace of something outside the self, in the name of that which we refer to as God, but which also includes the self and is God.

Barry Lopez, Arctic Dreams (London: Picador, 1986)

Driving east from Murupara you can watch the landscape suddenly slip from the grip of the great colonial project. Pastoral plain and pine plantation yield to the primordial, as abruptly as tarseal becomes loose gravel. Up against the wild forcefield of Te Urewera, Britain of the South just gives up.

It is different here, and Colin McCahon knew it. The West’s cataclysm of chance has been through Te Whāiti, Ngāputahi, Ruatāthuna, and Maungapōhatu, as it has every Pacific village. But dispossession here, as with the empires potentials for obliteration, has had but a shadow of it’s success elsewhere in Aotearoa. Te Urewera’s Māori land lies without the gangs of Pākehā farms that now inevitably surround it in other New Zealands, and remains unfazed by their urgent economics. It is as though Tūhoe’s history, their mountain fortress’s inaccessibility, has given them a strength that still sustains. While what now saturates the rest of the country may circle Te Urewera on all sides, it can’t enter. It is as though the land’s life-force is still Māori.

Yet somehow the possibility is betrayed by the way the Māori clearings seem to shrink from what encircles them. The driver too feels diminished by the wild life outside, compared with the passage through a domesticated landscape. Road maps confirm what the view hints. This is the South Pacific, not England. A dark, elemental, forever forest, not to be entered unless you know precisely what you’re doing. Primordial, Gondwanan, shrieking with birds, but unhaunted by the human history that brings time – or landscape – into being. Pacific gods – Papatūānuku, Tāne – have a longer stake in it than Christianity’s one, but the distinction is trivial. This has long been its own place. Brutal news for those who like to call the landscape theirs.

…

Colin McCahon’s eyes needed more than picturesque forest scenery. His peering out of the car window – a constant I gather – was a vital part of his process of looking into ‘New Zealand’, our situation here, and figuring out how to show it to us. His pictures, as he called them, can take the wind out of us, exposing the damage to what another discomforting voice, the cartoonist Michael Leunig, calls our soul’s ‘great, delicate, interconnected ecology’. McCahon was scared by the huge gap in our practical knowledge of ourselves in these ancient islands – dislodging what was here by nature without learning much about it – created by the settler psyche and pieties. ‘Something logical, orderly and beautiful’: these now-celebrated words express his earliest conscious sensing of qualities ‘belonging to the land but not yet to its people. Not yet understood or communicated, not even really invented.’ he meant Pākehā people, in the main, and he decided he would be the inventor. In the process, he created himself an envoy of the power and magic of art such as New Zealand had not experienced before.

Really good art burns itself into your memory and shapes your sense of place. Colin McCahon knew that his encounter with this stretch of country and its diminishing of human projects produced something seminal.

…

Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad’s famed exposé of colonial misdemeanor in Africa, has been label an inveterate piece of racist imperialism. But the darkness Conrad sensed in ‘the primeval forest’, as impenetrable as the darkness in Congo eyes, was not a phenomenon confined to the African arm of the empire. D.H. Lawrence sensed in Australia what Monte Holcroft called ‘the primeval shadow’ here, McCahon painted it, and, inevitably in a culture that is in decolonisation mode and has such a hard eye for tall poppies, some have used that to have a go at him. His inventions have been branded ‘Pathetic Projections: Willfulness in the Wilderness’ by those who detect in them a presumption to be the first speaker in and otherwise ‘silent’ land – a thousand years of Māori settlement notwithstanding.

Yet Colin McCahon’s ‘deeply coded community of signs’ have been compared to Aboriginal songlines. Just as few imagine ecology as being a site for finding answers to the question of whether peace can be a foreground rather than background, landscapes are full of things that most people simply don’t see. Some may look at the landscape and notice the light and the dark, the vulnerabilities and regenerative life forces in the shifting, chancy interplay between culture and nature. The appearance in the mind, even, of a symbol or two. But they’re more likely to move onto another view before the prospect can affect them. Moving left to right, those who would enter his landscapes, must walk along them as Pitjantjtjara and Aranda do their songlines, being cued in to who and where they are, where they came from, and how they relate to what’s going on.

Colin McCahon once said that his landscapes weren’t landscapes. But in interpreting a place through symbol and imagination, they heighten our own perceptions in ways that are rarely permitted by the ordinary process of ‘seeing’. Eyes feeding on the wildness pressing in on him, he came along this road because these dark, primal Aotearoan hills has something to tell, and he’d been asked tell it. Seeking truth in a peculiarly hard place.

…

‘Of the reasons for preserving a fragment of the landscape,’ one of the most insightful readers of landscape has said, ‘the aesthetic is surely the poorest.’ Waikaremoana is particularly beautiful New Zealand scenery, in the midst of what Elsdon Best, writing for tourists, called a ‘picturesque region’. But McCahon was suspicious about beauty of that kind. In a national park, of all places, he seeks to take us out of the world of visibly charged beauty – showing New Zealanders how their preoccupation with scenery, their possessing it ‘preserved’ in reserves, and their dogma that it’s a necessary ingredient of a painted landscape, trapped them in a particular sense of beauty.

‘How to keep… Back Beauty, keep it, beauty, beauty, beauty… from vanishing away?’ asks a poem McCahon was fond of quoting. ‘Give beauty back, beauty, beauty, beauty, back to God, beauty’s self and beauty’s giver.’ We do not own what appears to be most ours, most easily grasped, says Gerald Manley Hopkins, the poet. We have no claim on it – ‘preserving’ it for example – because what is at risk does not belong to us anyway.

What McCahon called his ‘interest in landscape as a symbol of place and also of the human condition’ was central to Hopkins poetry. Hopkins considered the filtering inward of nature to self that he recorded in his contemplations of nature to be so crucial to real understanding that he coined a word for it, a word now used by poets, painters and ecologists alike.

‘Inscape’ is the unfolding of the particularities of nature and the lineage of our encounters with it that put sensory perceptions of a landscape trigger. It’s the antithesis of what strangers’ eyes perceive, ‘unknown and buried away… and yet how near at hand it was if they had eyes to see it’, Hopkins wrote. Inscape distinguishes ‘the Māori landscape’ from the Pākehā one. It allows for both despair and delight at the sight of manuka-covered hillside in the bloom of regeneration. It makes those in New Zealand who are of European descent aware that their colonial project brought an inner landscape, so to speak, across the world, and one which differed at every point from what they found here. It was a kind of self-protective psychological compensation, the Australian Judith Wright has ventured, that made us burn, shoot, chop down and destroy whatever we could, replacing it, ‘if at all with something nearer to the heart’s desire’.

Hopkin’s poetry has been labeled linguistic nationalism for its profound shift from the standard Latin ‘correctness’ of mid-nineteenth century Catholic England to vernacular dialects of Anglo-Saxon folklore and custom. McCahon drew long and sustainingly from Hopkins for much of his painting life, and equivalent nationalism emanates from his landscapes’ candid hostility to the saturating prevalence and power of ‘the picturesque’ in New Zealand landscape painting rules. Inscape, said Hopkins, is ‘the very soul of art’. And just as, without that, he could not describe, in words, the processes and relationships he saw around him, McCahon, similarly, had to devise his own enabling vocabulary of signs.

– you bury your heart, and as it goes deeper into the land

you can only follow. It’s a painful love,

loving a land.

It takes

a

long time.

‘I belong with the wild side of New Zealand’ – The flowing land in Colin McCahon.

Originally written as a commissioned essay for a book to accompany a major exhibition of Colin McCahon.

The exhibition did not eventuate.

Theatre Country: Essays on Landscape and Whenua

Geoff Park

Victoria University Press

2006

___

Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith

Marja Bloem and Martin Browne

Contributions by Rudi Fuchs : William McCahon : Murray Bail : Francis Pound : Steven Miller

Craig Potton Publishing

2002

___

R

Note: This will be the last post on History of Our World.

To those who viewed, commented or supported the website, thank you.

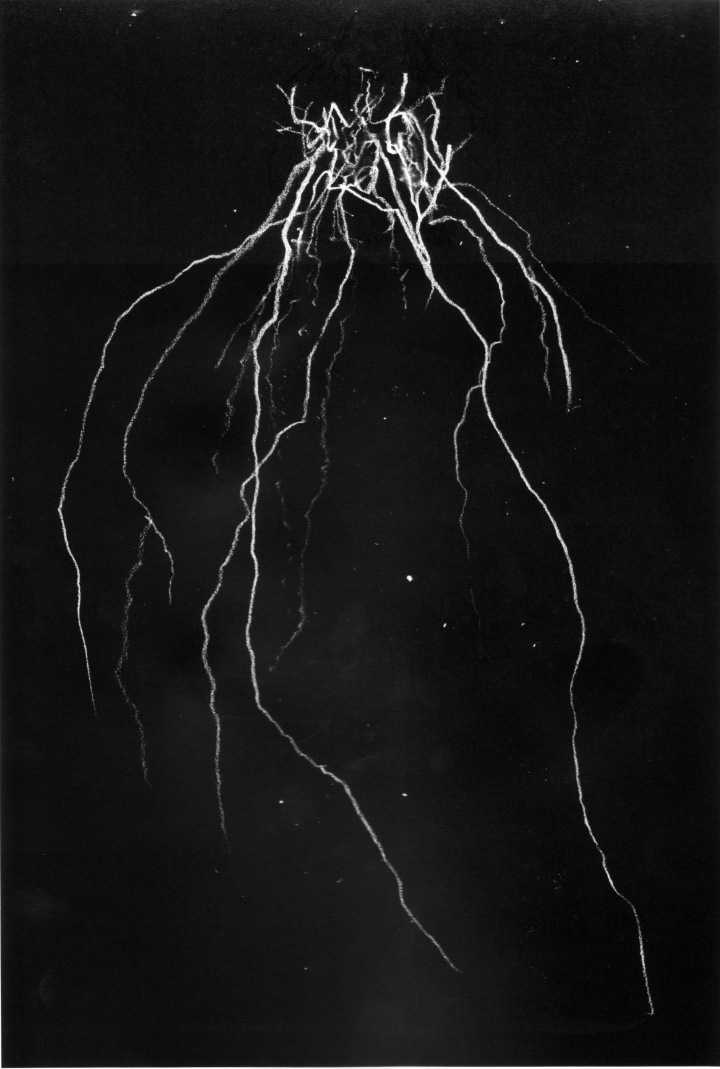

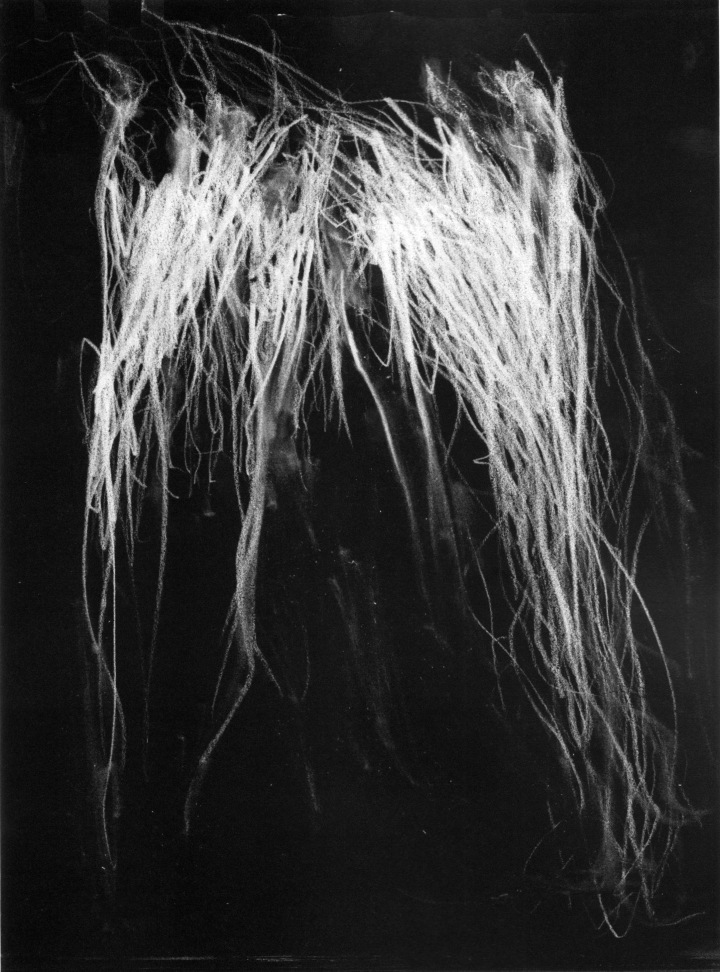

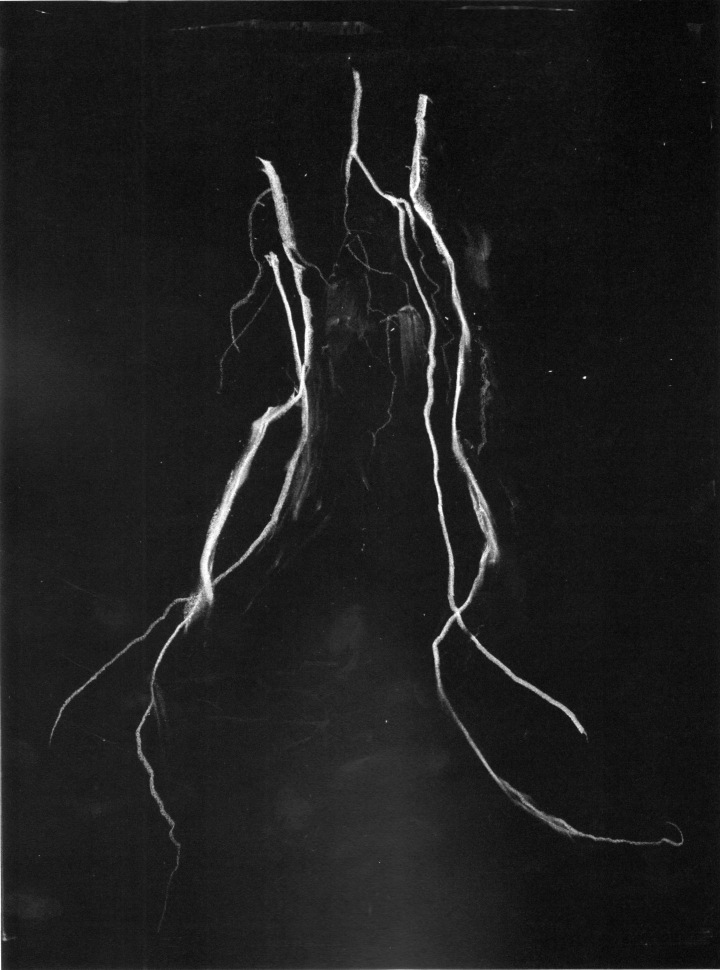

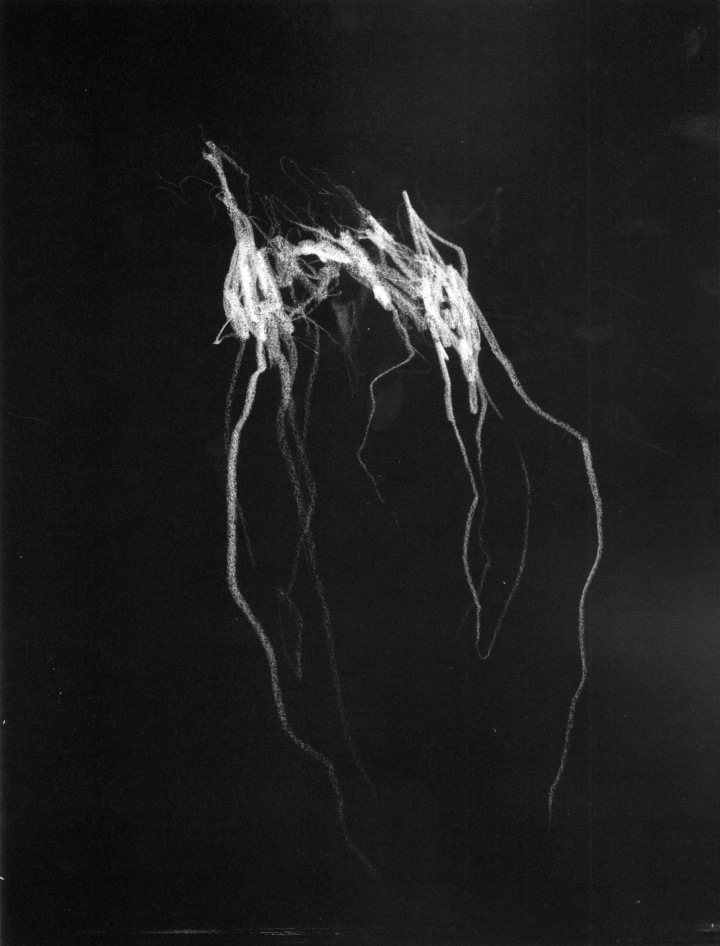

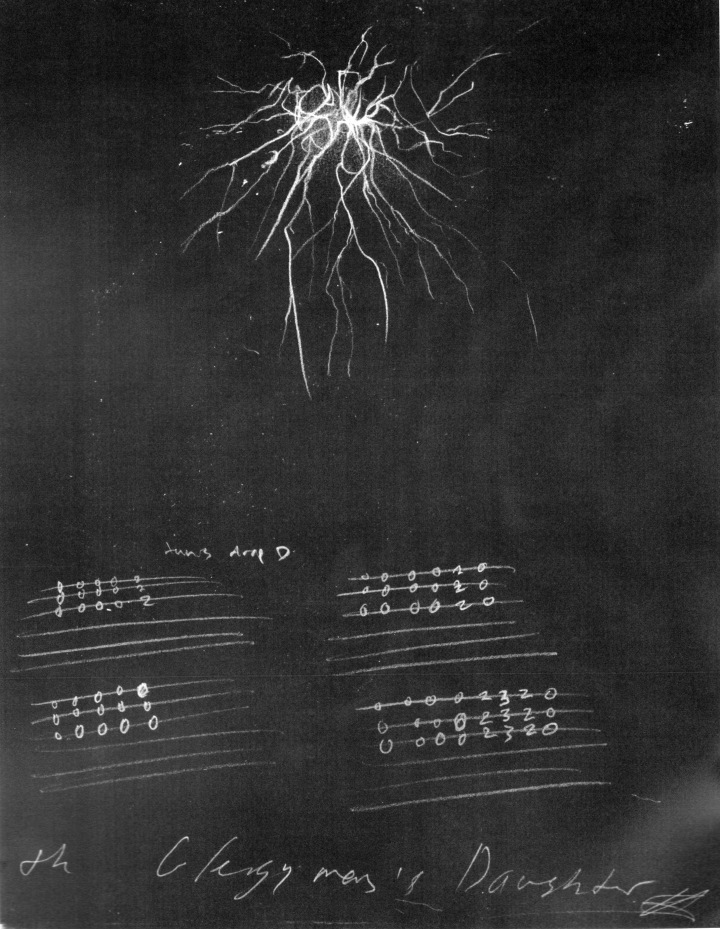

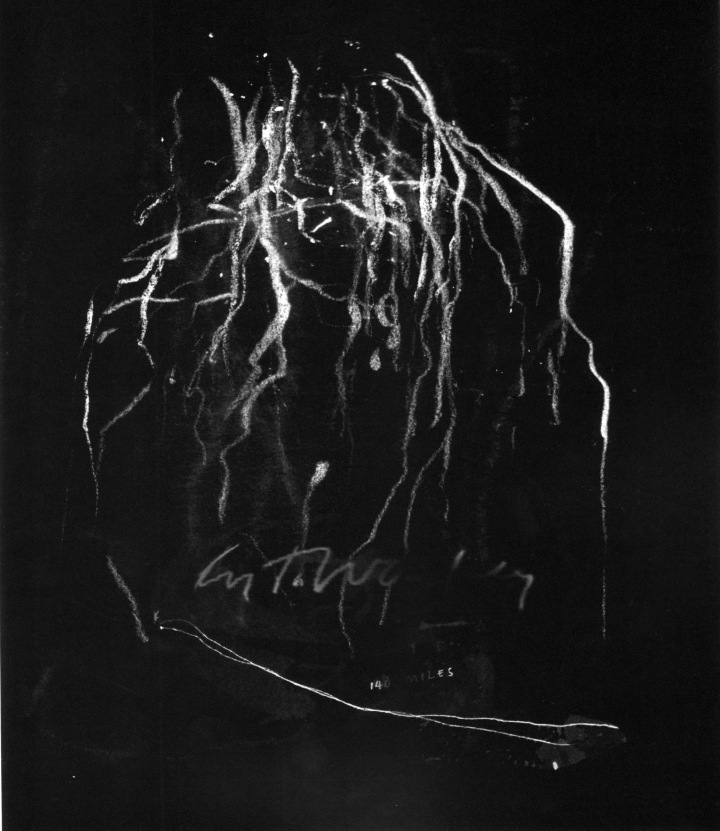

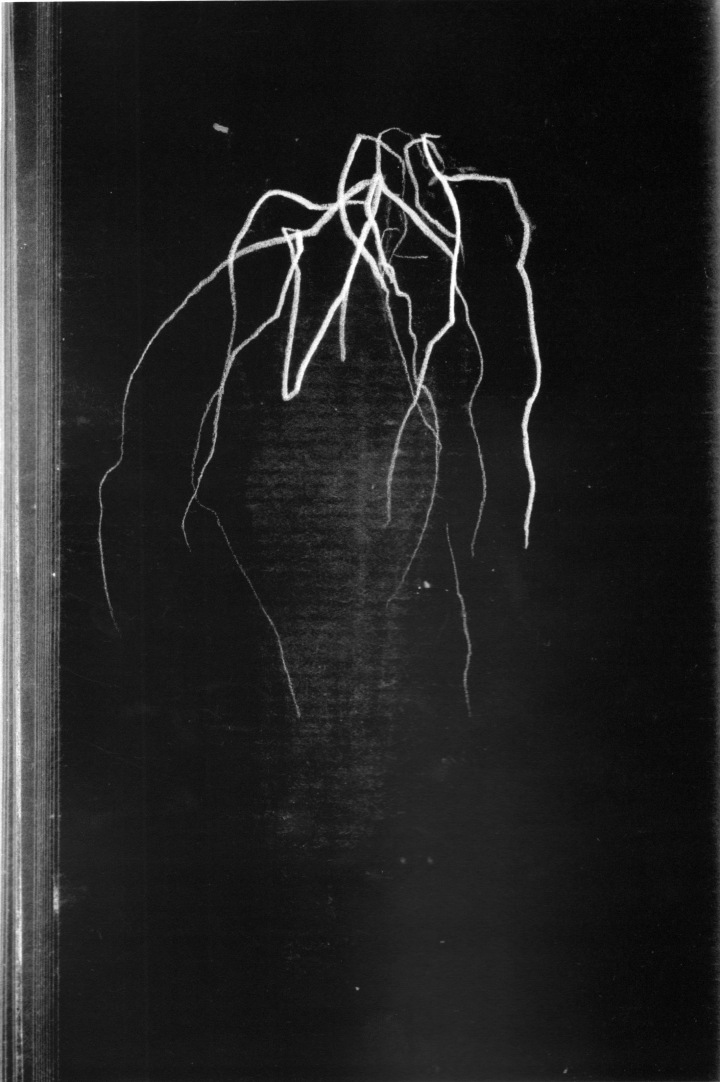

BLACKMETALCYTWÖMBLY / Volumes I, II & III | Andrew McLeod

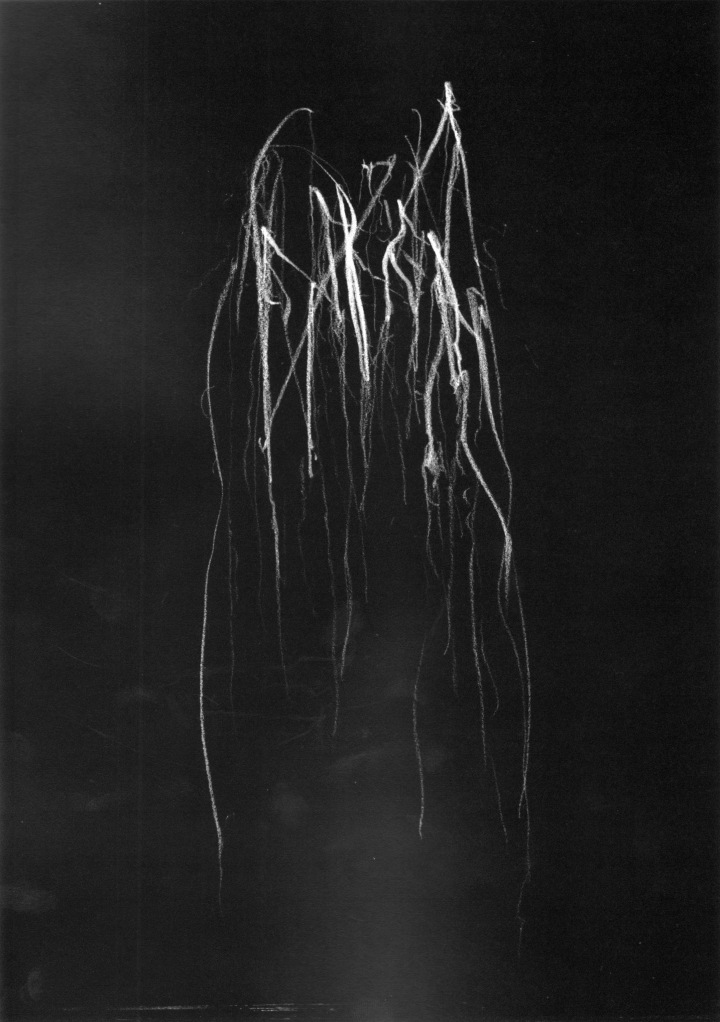

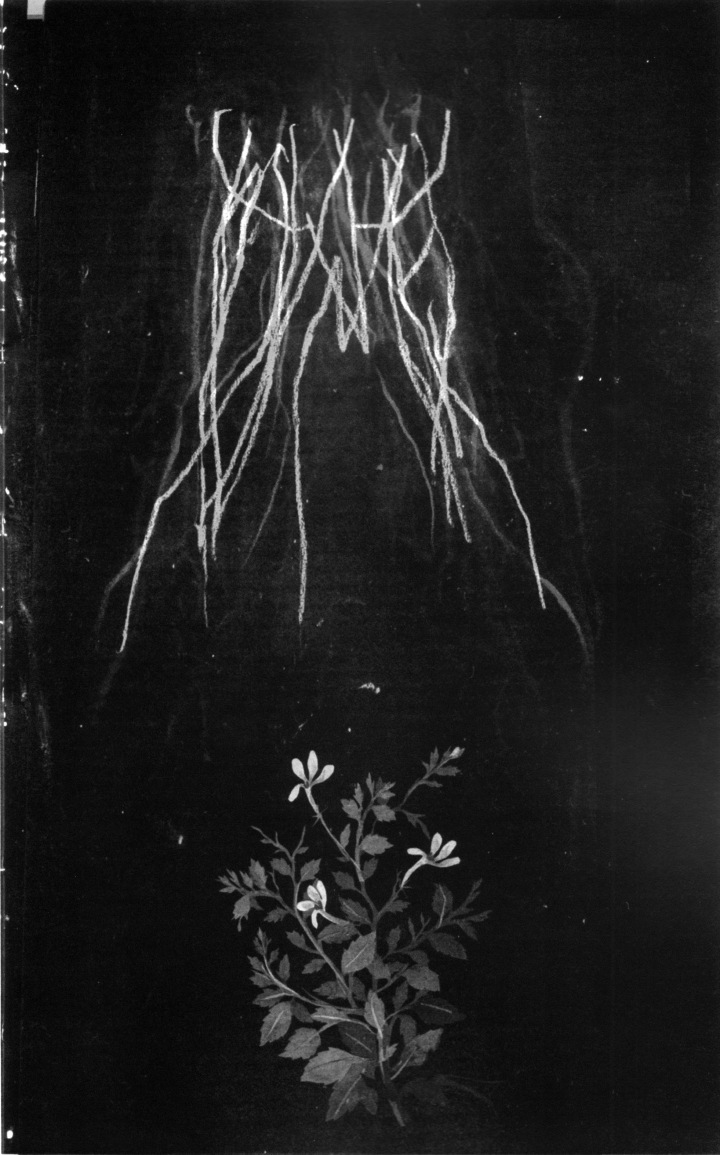

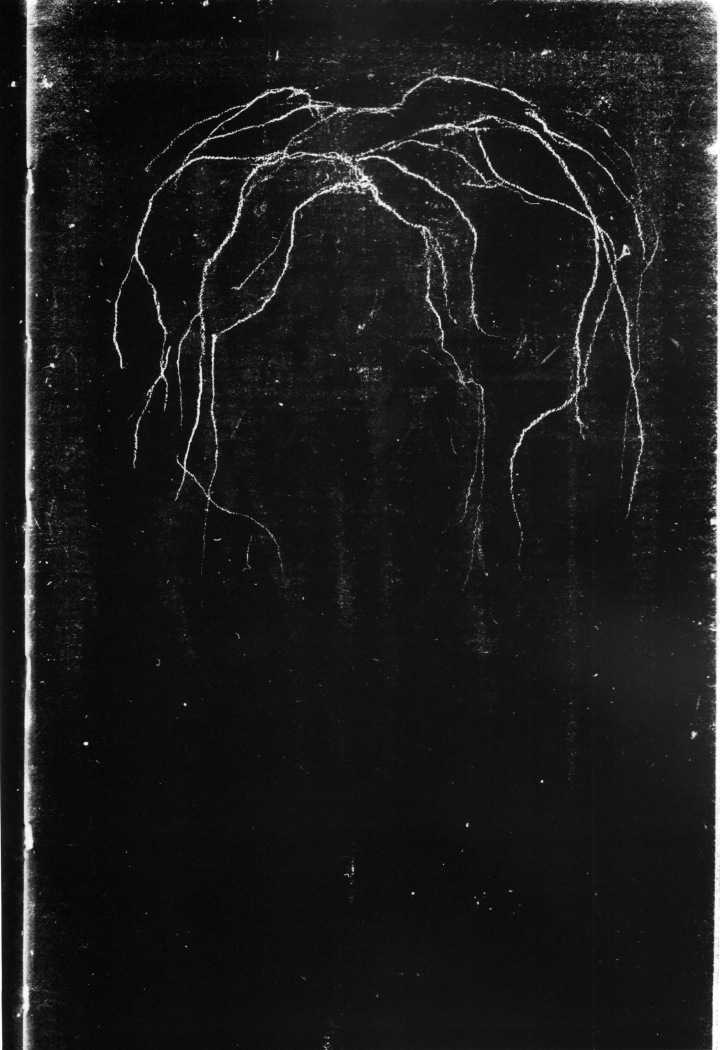

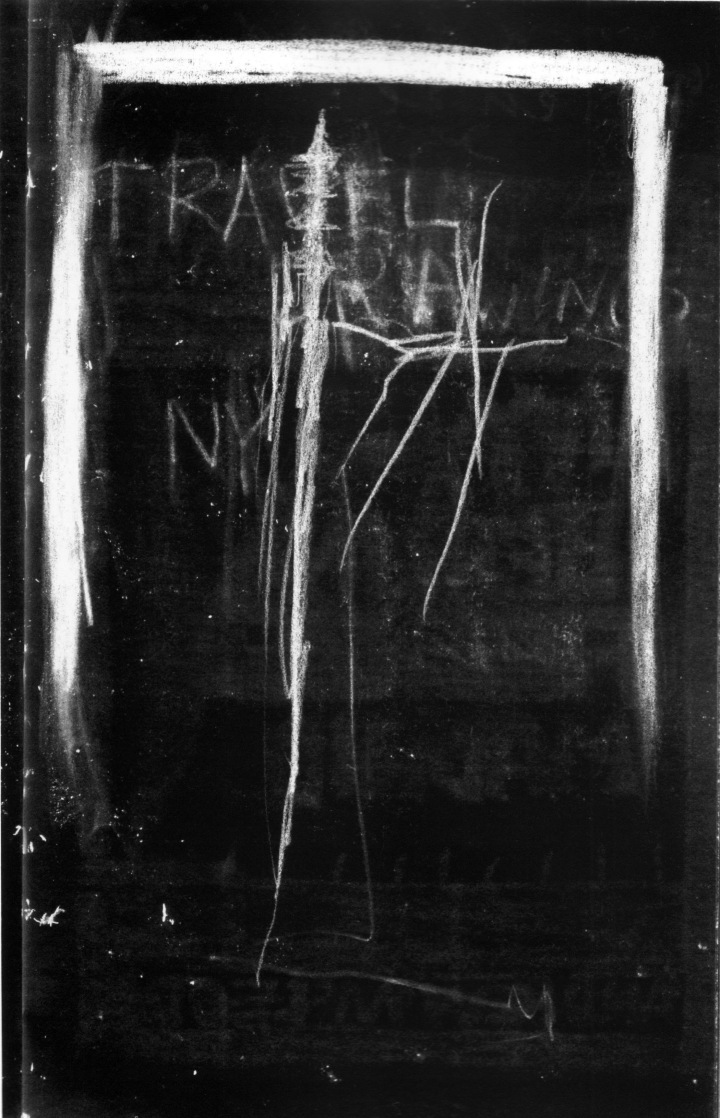

BLACKMETALCYTWÖMBLY / Vol. I, 2010 (unpaginated)

BLACKMETALCYTWÖMBLY / Volume II, 2010 (unpaginated)

BLACKMETALCYTWÖMBLY / Volume III, 2010 (unpaginated)

___

BLACKMETALCYTWÖMBLY / Volumes I, II & III

Andrew McLeod

2010

___

R

12 | 2010

___

12

Icons by Nirmala

21st January, 2010

Wunderkammer Studio

62 Ponsonby Rd, Auckland

___

R

Handboek | Ans Westra

James K. Baxter, 1972

Main Street – Wairoa, 1964

Dance – Auckland Maori Community Centre, 1962

Mongrel Mob Convention – Porirua, 1982

Turangawaewae Marae – Ngaruawahia, 1963

Hone Tuwhare at James K. Baxter’s graveside, 1972

Born in Leiden, the Netherlands, Ans Westra came to New Zealand in 1957. In a few short years she was to commence on her life-long photographic journey documenting the lives of New Zealanders during a period of cultural, social and generational change.

The comfortable conformity of the late 40’s and 50’s in New Zealand was about to be disrupted by the increasing post-war arrival of European migrants and, more importantly, the urban shift of Māori, which gained momentum in the 1950’s. As a society New Zealand and it’s citizens were far from prepared to accommodate the difficulties accompanying such a challenge to their homogenous cultural, social and institutional frameworks.

Ans Westra’s arrival in New Zealand coincided with that shift and the resultant changes and tensions which have characterised and continue to characterise New Zealand’s social and cultural evolution.

___

Handboek | Ans Westra Photographs

Luit Bieriga : Christina Barton : Gavin Hipkins : Lawrence McDonald : Kyla McFarlane : Cushla Parekowhai : Damian Skinner : John B. Turner

Blair Wakefield Exhibitions (BWX)

2004

___

R

Out The Black Window | Ralph Hotere, 1997

‘Rain’, 1979. Oil and enamel on unstretched canvas, 2440 x 985 mm. Collection of A. and J. Smith, Auckland.

RAIN

I can hear you

making small holes

in the silence

rain

If I were deaf

the pores of my skin

would open to you

and shut

And I

should know you

by the lick of you

if I were blind

the something

special smell of you

when the sun cakes

the ground

the steady

drum-roll sound

you make

when the wind drops

But if I

should not hear

smell or feel or see

you

you would still

define me

disperse me

wash over me

rain

– Hone Tuwhare

At the forefront of New Zealand painting for over three decades Hone Papita Raukura (Ralph) Hotere was born in the remote Northland settlement of Mitimiti in 1931. After studying in England and Europe in the early 1960s, he returned to New Zealand and has been based in and around Dunedin since 1969, producing some of his finest work in collaboration with such poets as: Cilla McQueen, Bill Manhire, Hone Tuwhare and Ian Wedde. A member of the Aupouri tribe, Hotere has also incorporated traditional Maori poems into his artworks. These works have served as a bridge for New Zealand’s literary and visual art worlds and the association between the two has been resonant and vital in the development of this country’s cultural history.

___

Out The Black Window | Ralph Hotere

Gregory O’Brien : Ian Wedde

Godwit Publishing : City Gallery, Wellington

1997

___

B

Aberhart | Laurence Aberhart

Plate 8 – Detail #4 (obliterated portrait), Waikumete Cemetery, West Auckland, 8 February 1993

Plate 72 – Watchtower near Toi Shan, Guangdong Province, China, 27 November 2000

Plate 83 – Mount St. Michel, Normandy, France, 12 October 1994

Plate 104 – Dargaville (Mt. Wesley Cemetery), Northland, 17 April 2003

Plate 110 – Mater Dolorosa, 18 December 1986

Plate 183 – The Prisoners’ Dream 3 (Taranaki from Oco Road, under moonlight), 27-28 September 1999

Plate 185 – The Prisoners’ Dream 5 (View #2. Ripapa Island, Lyttelton Harbour), 14 March 2000

Plate 212 – A distant view of Taranaki from the mouth of the Wanganui River, at dusk, 3 February 1986

Laurence Aberhart has been at the forefront of New Zealand photography since the late 1970’s, and is recognized as a major international figure. Like the paintings of Colin McCahon – an artist whom Aberhart is frequently paired – his photographs are a sustained meditation on time, place and cultural history.

___

Aberhart

Laurence Aberhart : Gregory O’Brien : Justin Paton

Victoria University Press

2007

___

R

Max Gimblett

Cloak – a New Zealand Childhood, 2001.

Delacroix & Caduceus, 1994.

Crown, 1991.

Either/Or, 1983.

Mountains and Text, 2001.

The Wheel, 1998.

With philosophies and practices that encompass influences as varied as Abstract Expressionism, Modernism, Eastern and Western spiritual beliefs, Jungian psychology and ancient cultures, Max Gimblett’s work holds a special place in recent New Zealand art history.

Born in New Zealand, Gimblett has been primarily based in New York since 1972, and continues to exhibit regularly in both places. This ‘straddling’ of countries, and the travel that goes along with it, is of great significance to Gimblett’s ideology and work. His range of shaped canvases covey the various aesthetic and cultural associations connected to the oval, rectangle, tondo, keystone, and quatrefoil, exploring the multiplicity of meaning attached to these revered objects. The quatrefoil shape, for instance, dates back to pre-Christian times and is found in both Western and Eastern religions symbolising such objects as a rose, window, cross and lotus.

Materials such as gold and silver draw upon their religious associations with honor, wisdom, enlightenment and spiritual energies, bringing a seductive quality to many of Gimblett’s works. Carefully prepared and cured, combinations of gold, silver, copper, bronze, epoxy, resin, plaster, paint and pigments also present a sense of extreme delicacy. However these serene surfaces are more often than not disturbed by bold gestural brush marks in acrylic polymers and paints, made using Gimblett’s extensive collection of brushes, mops and rollers. These drips, splatters and swipes of paint strongly ground his works in the tradition of American Abstract Expressionism; yet at the same time maintain a link to Eastern calligraphic practices.

___

Max Gimblett

Essays by Wystan Curnow & John Yau

Craig Potton Publishing

In Association with Gow Langsford Gallery

2002

___

A

Jingle Jangle Morning | Bill Hammond, 2007

Passover, 1989. Acrylic and varnish on aluminum, 1200 x 613mm. Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery – Toi o Tamaki.

Shallow Graves, Enderby Island, 1990. Acrylic on aluminum, 550 x 620mm. Private Collection.

Buller’s Table Cloth, 1994. Acrylic on canvas, 1682 x 1675mm. Collection of Auckland Art Gallery – Toi o Tamaki.

Camoflage, 1997. Enamel on hinged panels, dimensions variable. Collection of Peter and Ann Webb.

Zoomorphic Detail, 1998. Acrylic on canvas. Private collection.

Unknown European Artist, 2004. Acrylic on canvas, 2000 x 1200mm. The Stevenson Collection.

Ancient Pitch, 2007. Acrylic on canvas, 1200 x 1800mm. Private Collection, Wellington.

Bill Hammond occupies a unique place in New Zealand art history; he has established a visual language and a painterly technique that are wholly his own. The enormous breadth of material found in his work reveals an artist who is constantly working, always thinking about the next painting and the next direction. His paintings change in mood throughout his career, from the frenetic works of the 1980’s, to the cynical expose of human exploitation of native flora and fauna, the rock surrealism of the 1990’s, and to his later works which increasingly explore mythical realms and reveal a disciplined richness and poetic depth.

A distinctive pictorial language has unfolded over thirty years of practice, tapping into elements of the decorative arts, popular culture, New Zealand history, symbolism, surrealism, Renaissance art and, notably, Ukiyo-e (Japanese woodblock printing) and paintings by the fifteenth-century artists Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder. It is his interpretation of their significance for his own means, that makes his art so spellbinding.

Hammond’s acute eye for the macabre and the beautiful conflate in his celebrated Buller series of painting. It is these, his signature bird creatures, watching, waiting and poised amid emerald forests, that have led to Hammond often being thought of as the artist of luxurious and intense bird paintings that decorate expensive interiors. Birds feature in creation myths, stories and parables across all cultures, and it is through their depiction that Hammond is able to deliver an analysis of humanity, or in the case of the Buller series, humanity lost. Over more than two decades a nation of – and other shape-shifting creatures – has populated Hammond’s canvas realm. From the maligned birds of the Buller series, to the ominous flock that occupies his zoomorphic paintings of the late 1990’s, the birds rise above us through a world of limbo where, regal and godlike, they remain uncomfortably watchful.

From early beginnings as an art student in Christchurch, Hammond has consistently displayed an oblique wit. His observations of the world around him, and the ever-present influence of music and popular culture, are a constant beat in his practice. Pop, rock, classical, jazz and punk music not only provide endless emotional scenarios but also a way of approaching the act of painting. The ritual of performance in theatre, dance or music, playing the drums or mixing on a sound desk, materialize into staccato paintings. As a practicing musician himself, Hammond’s compositions are, as he once said like an instrumental ‘laid out flat’, replete with choruses and rhythms.

It is well known that Hammond ‘doesn’t do interviews’, that he is a private person who refuses to talk about his work. This presents quite a challenge for any curator or historian charged with the task of unravelling the many threads of his practice, yet it also confronts anyone who approaches his paintings. And this is exactly what he wants: for people just to look, to bring to the paintings their own reflections and to be open to receiving an extraordinary visual experience that has the ability to transport them to other worlds.

– Jennifer Hay

___

Bill Hammond | Jingle Jangle Morning

Jennifer Hay : Lawrence Aberhart : Chris Knox : Ron Brownson

Christchurch Art Gallery – Te Puna o Waiwhetu

2007

___

Christchurch Art Gallery – Te Puna o Waiwhetu

R

White Silence: Grahame Sydney’s Antarctica, 2008

Flags denote ‘roadways’ and safe paths across the ice. Red and green flags are a sign of safe passage, black flags mean danger.

A natural monochrome: the dark volcanic stone of Observation Hill meets the sea ice on a cloud-blanketed day.

Pegasus Airfield, on the permanent Barrier ice. The Constellation aircraft crashed on landing years ago, and is slowly being swallowed by the wind-blown snows.

Condition One blizzard at McMurdo, November 2003.

Everyone is a visitor in the Antarctic: no one belongs. One or two secretive lichens aside, there is no life away from the ocean; too far straying from the life support of the sea and all animal life perishes. Nature makes it abundantly plain that this is no place for humankind, and that our presence on the sterile frozen continent is a temporary pass, as unwelcome and inappropriate as on the moon.

Grahame Sydney was born in Dunedin in 1948 and gained his secondary education at King’s High School. Though art classes were not on offer (Sydney learnt his painter’s craft through private classes) there was a Camera Club, and he was introduced to photography under the inspired tuition of the late Reg Graham. While photography remained a satisfying pastime well into Sydney’s adulthood, it took a back seat to the development of his painting. Sydney embarked on a full-time artist’s career in 1974. Working in egg tempera, watercolour and oils, his paintings have been widely exhibited and are held in private and public collections around the world. He also is both etcher and lithographic printmaker.

In November 2003 Sydney flew to Ross Island and, frustrated by attempts to paint in conditions where the brush hardened and exposed fingers threatened frost-bite within seconds, he turned again to the camera. So captivated by this lens-view of a frozen world, he returned in 2006 and took another series of photographs. Exploring a continent that appears at first glance to be devoid of colour, warmth or comfort, each image in fact reveals an extraordinary terrain that is solemn, sparse and poised with a magnificent stillness.

___

White Silence: Grahame Sydney’s Antarctica

Introduction by Grahame Sydney

Penguin Group

2008

___

A

Chris Watson, 2009.

Chris Watson, 2009.

Chris Watson’s work as a wildlife and environmental sound recordist is unparalleled. He has worked with the BBC recording and editing sound for many of David Attenborough’s great wildlife series such as The Life of Birds (1998), The Life of Mammals (2001), Life in the Undergrowth (2005) and Talking with Animals (2001) and has won numerous awards for these and other TV and radio documentaries.

As well as his work as a documentary sound recordist, Chris Watson is an artist in his own right and has produced three solo albums and many collaborative sound works. He constructs collages of sounds, which evolve from a series of recordings made at the specific locations over varying periods of time. Watson’s exploration of sound environments has taken him all over the world and has led to many bizarre and unconventional recording situations. He has recorded glacial shifts in Iceland, massive storms in the Baltic Sea, the voices and rhythms of the Humboldt current around the Galapagos Islands. Chris Watson’s performances take listeners to places hidden and inaccessible. It is cinema for the ears.

Chris Watson’s visit was made possible by alt.music and kindly supported by Adam Art Gallery, New Zealand School of Music and Frederick Street Sound and Light Exploration Society.

___

A

9 comments