How It Is | Miroslaw Balka

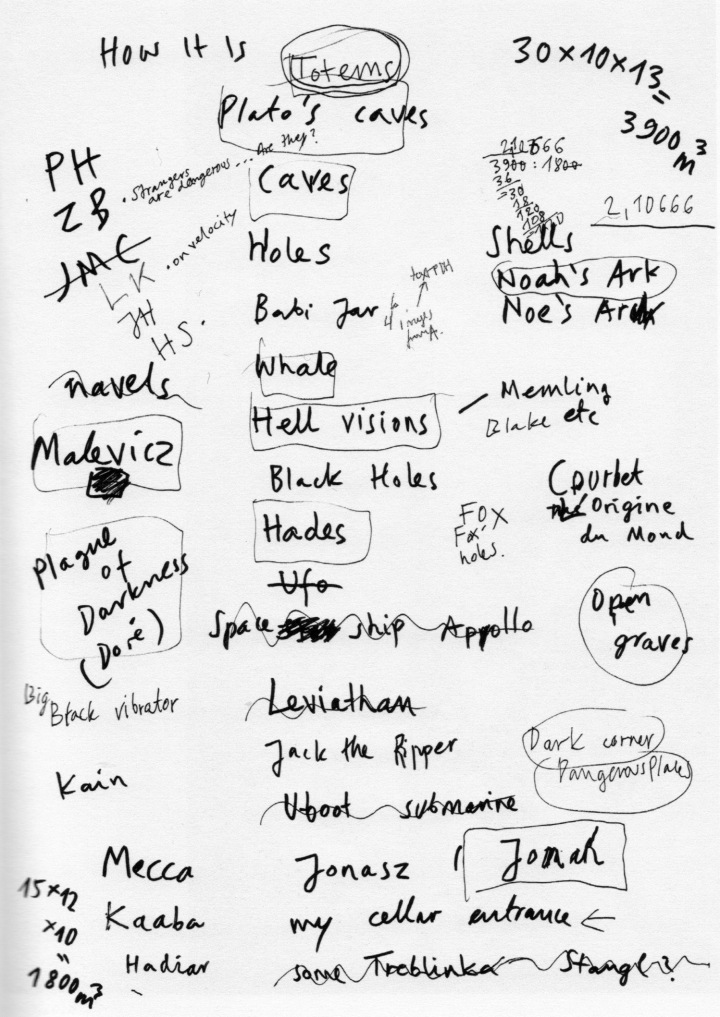

List of references for How It Is, April 2009

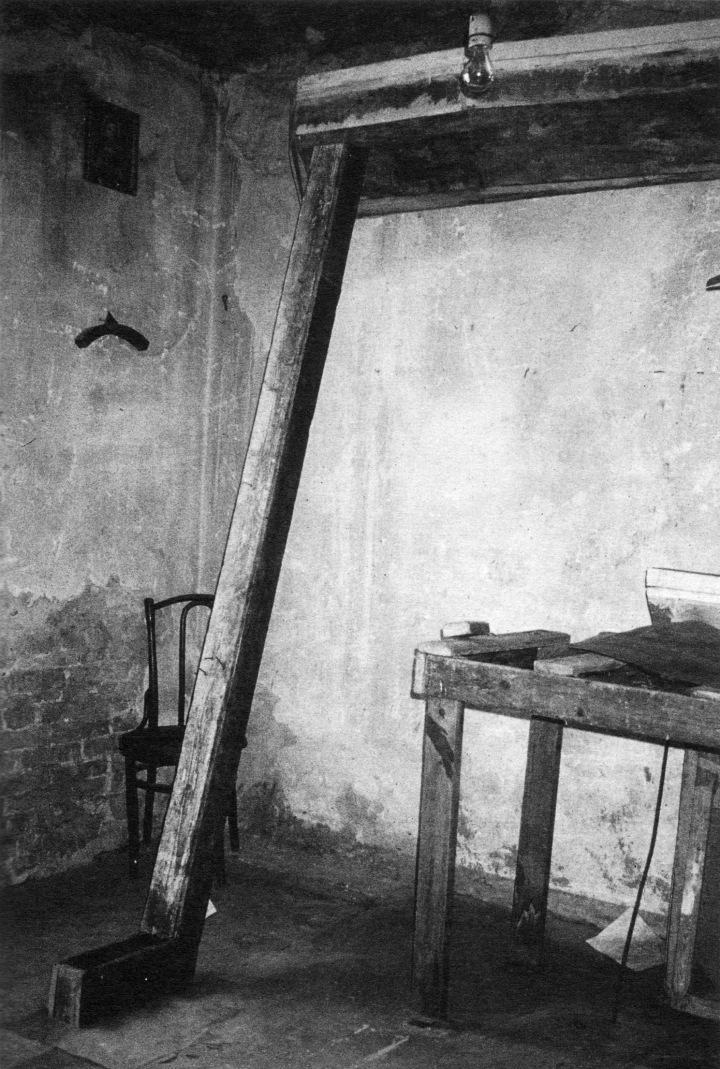

The artist’s studio with elements of Oasis (CDF), 1989

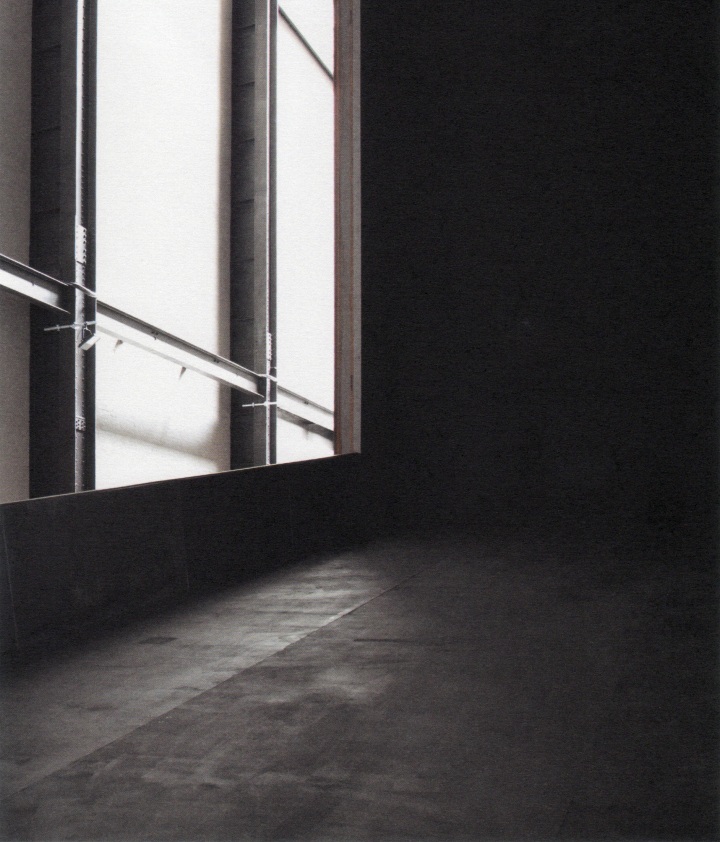

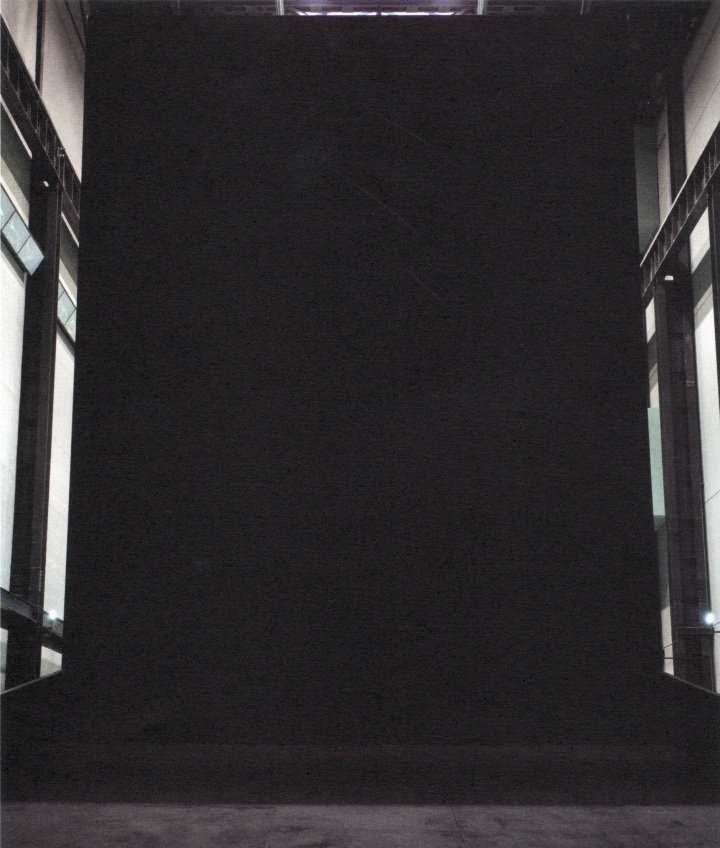

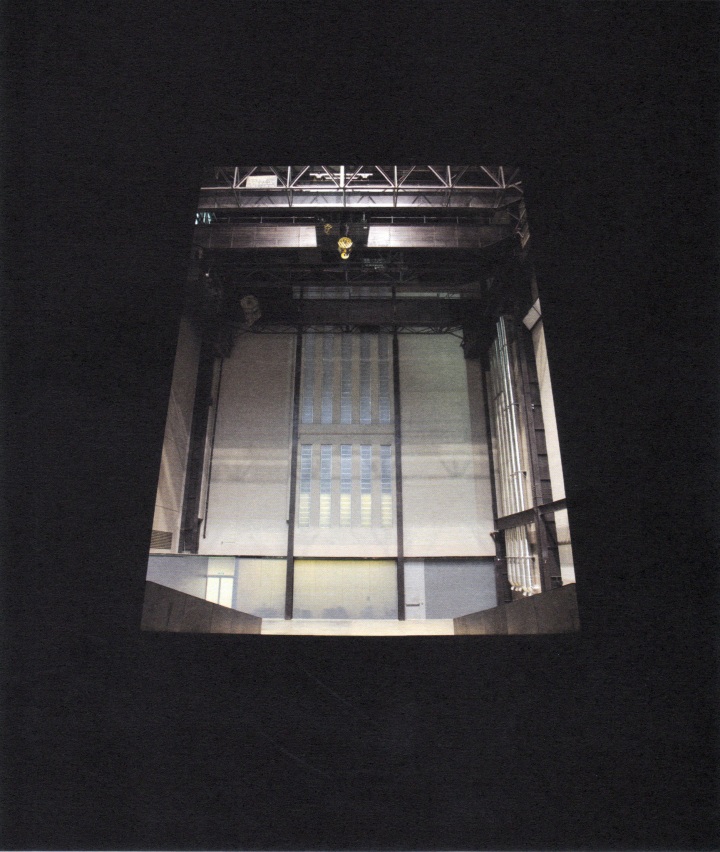

How It Is, 2009 (photography by Sam Irons)

Ancient myths and the pictures of the modern era that are based on these present the domain of Hades – the shadowy realm of the dead or literally darkness, that which we cannot perceive – a place filled with a multitude of terrors. However, it is not portrayed as just another place, as the negative of this world. Particular importance also attaches to the path to Hades, the path into the underworld marked out by the travelers arrival at the river Styx, separating our world from the next, the crossing of the styx in Charon’s barque, and the moment of appearing before the god Hades. The theological, philosophical and psychological meanings of this and other descriptions of this path into death are self-evident. Of necessity they resort to recognizable metaphors to explain something that has never been seen or understood. Real burial grounds, for instance those of the Ancient Egyptians or Neolithic man in Britain, also pay particular attention to the passage from this world to the next, where effort is required to make the journey from light into complete darkness. It is only relatively recently that Balka first contemplated this zone in his work, although there are earlier shades of it here and there that dissipate into the muted twilight that pervades most of his videos. More often darkness is indirectly evoked by somewhat weak lights. Later on, when he coats the walls of the exhibition space with a two-and-a-half-meter high, continuous layer of ash, or makes a long, narrow walkway with twists and turns from simple timber, although he may literally and metaphorically be working his way toward darkness, these pieces are presented in full light of the exhibition space. No so in the case of How It Is. As the viewer approaches, it looks like a huge container, a mighty sculpture with a powerful presence. However, walking round it brings one to something else entirely, and to a sudden halt. A fragment of memory: turning the pages of the philosopher Robert Fludd’s magnum opus of 1617 the readers may find, to their surprise, a large black square taking up much of page twenty-six. ‘Et sic in infinitum’ is inscribed into all four margins of the dark square: ‘And this into infinity’, a something that one cannot imagine. The non-picture comes at the beginning of a chapter about shadows and privatio, a word that translates as both ‘privation’ and ‘liberation’. Cut. The back wall of the colossal container has been lowered, forming a ramp into the darkness. What wonder or beats await us inside? Will we have the curiosity and calm determination of János in Béla Tarr’s movie Werckmeister Harmonies to pursue the unknown, in astonishment, or will we gaze at it from the outside, uninvolved and suspicious? The steel room is large enough for its depths to be shrouded in mystery as we enter, but it is also wide enough to move about freely inside it – alone or with others. It is not pitch black inside, just increasingly dark; turning around we can still see the outside. The mise-en-scene of the unknown is overwhelming, but not because the Turbine Hall where it is placed would dwarf any smaller structure. The fact is that might raised up steel body – as tall as a house – corresponds in size to our inner sense of the unknown, of the limits of life. The effort and huge amount of material that went into making it were necessary to convey the notion, the fear, the black block that weighs us down on the last path. The sculpture had to become almost absurdly large in order to give a true sense of the threat that looms at us in the shape of the last wall in the realms of our imagination. However, when one in fact enters the black box, there is no climax to this sense of the overwhelmingly uncanny, instead there is a kind of gradual dis-illusion as one becomes accustomed to the darkness, an insight into ‘how it is’. Privatio: deprived of the certainty of life yet also liberated from the fear? The black container is a paradox. It has the dimensions of fear and is large enough to accommodate a social event, but it also has the intimacy of an individual thought and the normality of a single life.

Julian Heynen (Translated by Fiona Elliott)

___

How It Is

Miroslaw Balka : Zygmut Bauman : Julian Heyene : Paulo Herkenhoff : László Krasznahorkai : Helen Sainsbury

Tate Publishing

2009

___

Tate Channel: The Unilever Series: Miroslaw Balka

R

Building Images | Lucien Hervé

Charlotte Perriand Chair, Unité d’Habitation, Marseille, Le Corbusier, architect; 6 x 6 negative.

Wall in Belleville, Paris, 1947; vintage print.

Knossos, Crete, 1956; vintage print.

Unité d’Habitation, Marseille, Le Corbusier, architect, 1949; 6 x 6 negative.

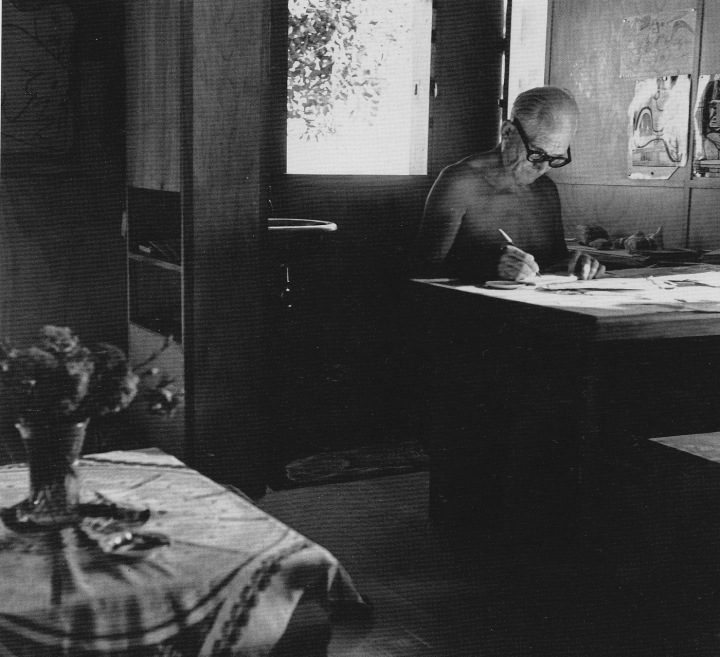

Le Corbusier in His Cabin, Cap-Martin, 1951.

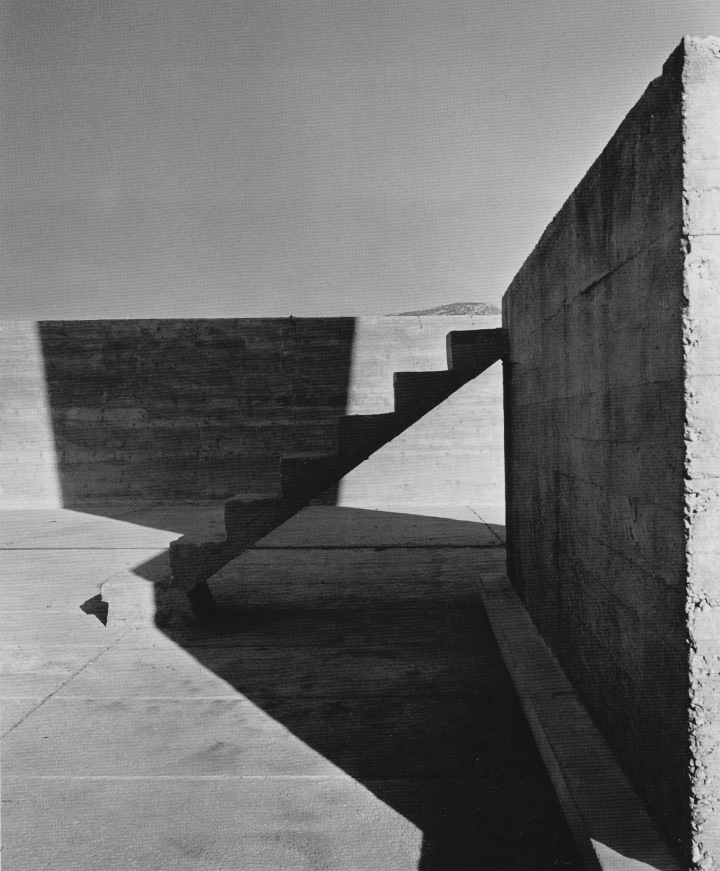

Chandigarh, the High Court, India, Le Corbusier, architect, 1955; cropped 6 x 9 negative.

Unité d’Habitation, Le Corbusier, architect, 1952; cropped 6 x 6 negative.

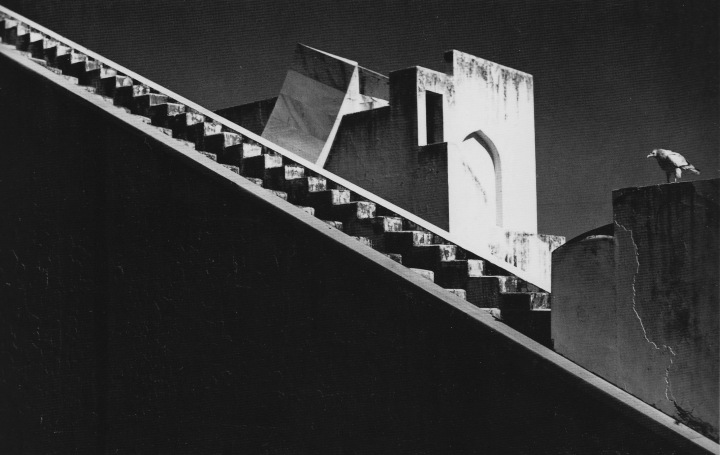

Jaipur, Observatory, India, 1955; cropped 6 x 6 negative.

Ronchamp Chapel, Le Corbusier, architect, 1953; cropped 6 x 9 negative.

Chandigarh, The High Court, India, Le Corbusier, architect, 1955.

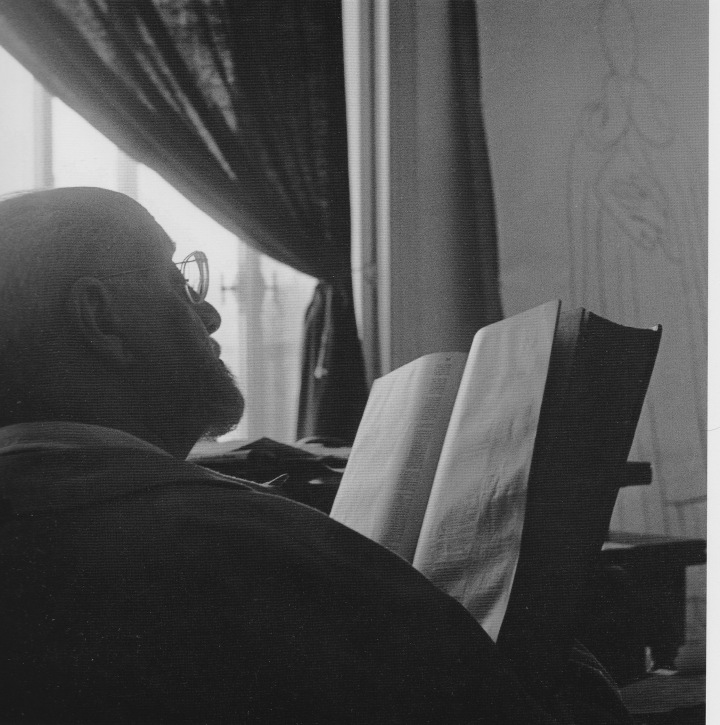

Henri Matisse, Painter and Sculptor, Hôtel Régina, Nice, 1949; 6 x 6 negative.

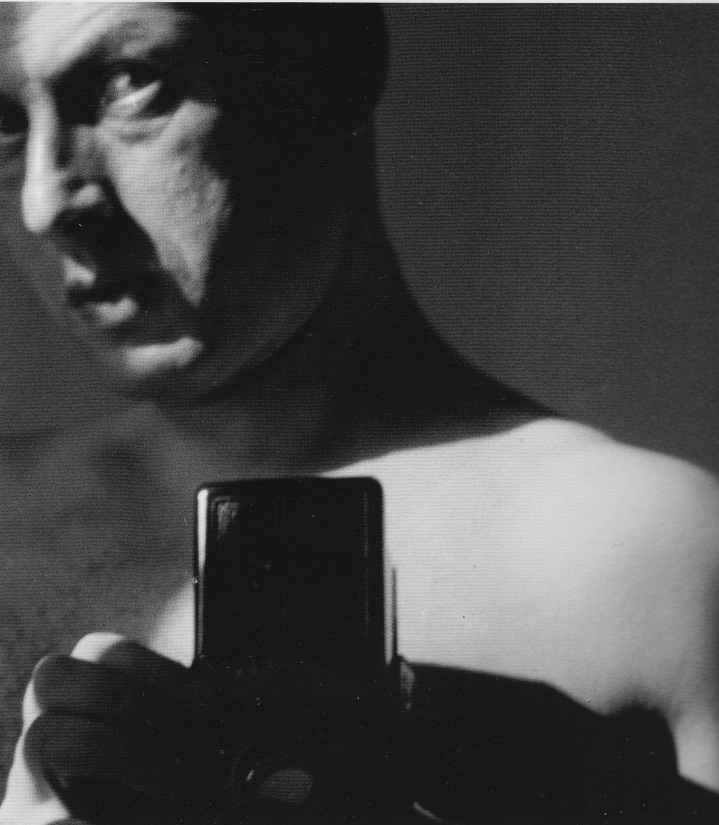

Lucien Hervé, Self Portrait, 1938.

Lucien Hervé was one of the great architectural photographers of the twentieth century and widely recognized for his collaborations with Le Corbusier from 1949 until the renowned architects death in 1965. Hervé approached his subjects, specifically the buildings he was commissioned to document, with a particular focus on conveying a sense of space, texture and structure. Through a strong contrast of light and shadow, Hervé defined the dialogue between substance and form as well as placing emphasis on building details. In this way, the photographer was able to communicate the depth of a room, the surface of a wall, or the strength of a buildings framework. However, Hervé the master of architectural photography has eclipsed Hervé the photographer, whose career began as early as 1938 and whose subject matter varied widely.

___

Building Images : Lucien Hervé

Oliver Beer

Getty Publications

2004

___

B

8 Untitled Works | Josie Miner

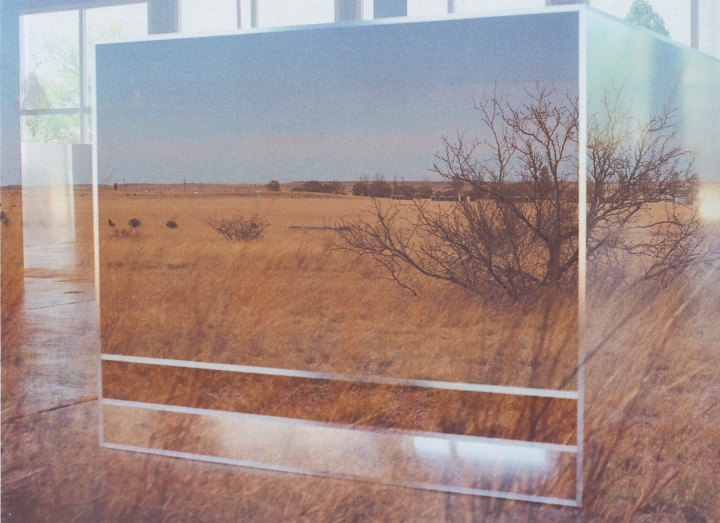

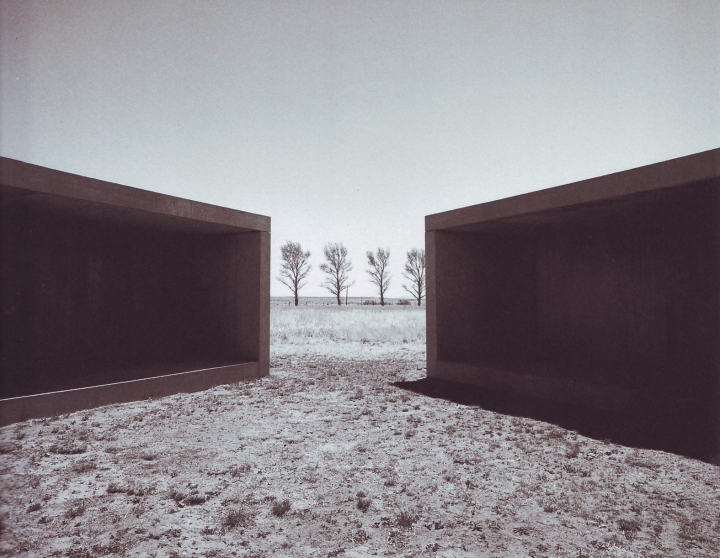

All fifteen concrete works by Donald Judd cast and assembled on-site in Marfa, Texas between 1980 through 1984. Each measures 2.5 x 2.5 x 5 meters.

Shade is short and miles away, tucked between the Chinati mountains and the Mexican border.

In the low, lonely horizontal blue desert plain of the Chihuahuan.

As day dims, light is long.

Bowing towards the horizon, the retiring sun sets the sky ablaze and the desert aglow.

A weightless, soft sensual glow : purple mountain silhouettes, capacious sky, undulating glass, amber cactus and concrete.

Light and dark, land and sky and blue and melt.

The cool, quiet haze of dark generously gives way to starry desert night dreams.

___

A Magazine #9

Proenza Shouler : Tom Watt : Ian Davies : Nathalie Ours

A Publisher

2009

___

A

Gordon Matta-Clark

Splitting, 1974. Black and white photo collage, 101.5 x 76.2 cm.

Splitting, 1974. Black and white photo collage, 100 x 72 cm.

Splitting, 1974. Black and white photo collage, 100 x 100 cm.

Splitting, 1974. Black and white photo collage, 50 x 60 cm.

Day’s End, 1975. Colour photograph, 96 x 103 cm.

Day’s End, 1975. Cibachrome, 121 x 103.5 cm.

Conical Intersect, 1975. From a series of five colour photographs, 101.6 x 106.7 cm.

Conical Intersect, 1975. From a series of five colour photographs, 101.6 x 106.7 cm.

Conical Intersect, 1975. From a series of five colour photographs, 101.6 x 106.7 cm.

Conical Intersect, 1975. From a series of five colour photographs, 101.6 x 106.7 cm.

Conical Intersect, 1975. From a series of five colour photographs, 101.6 x 106.7 cm.

Conical Intersect, 1975. Cibachrome, 101.1 x 76 cm.

Office Baroque, 1977. Cibachrome, 101.6 x 76.2 cm.

Office Baroque, 1977. Cibachrome, 108 x 58 cm

Office Baroque, 1977. Cibachrome, 101.5 x 75.6 cm.

“I don’t know what the word “space” means…I keep using it. But I’m not quite sure what it means.” – Gordon Matta-Clark.

From 1971 until his death in 1978, the American artist Gordon Matta-Clark produced a body of work popularly known the “building cuts”; sculptural transformations of abandoned buildings paradoxically constructed through the cutting and virtual dismantling of a given architectural site. Situated in places ranging from slums in Manhattan to the waterfront of Antwerp, these works, long since destroyed, appear to comply with the most canonical assumptions of site-specific art in the seventies. On the one hand they demonstrate the commonly accepted notion that the place where the artwork is encountered necessarily conditions its reception, foregrounding as they do the the localized dynamics between institutions, property values and works of art. On the other hand Matta-Clark’s cuttings address the temporality of the built environment, marking the destruction of the buildings that effectively constituted such places.

To read the personal testimonials on Matta-Clark’s work is to sense the experimental limitations of these models, for what marks these accounts is a certain failure of description that attends to the dizzying, at times overwhelming, experience of the building cuts; their unsettling shifts in scale, their Piranesiesque irruptions into architectural mass, their vertiginous drops and labyrinthine passages, their gaping holes, each affording the most disorientating vistas.

___

Gordon Matta-Clark

Thomas Crow : Corrine Diserens : Judith Russi Kirshner : Christian Kravagna

Phaidon

2003

___

Gordon Matta-Clark | Conical Intersect (1975)

B

Complete Works | Vincent Van Duysen

Photo essay by Alberto Piovano (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

Photo essay by Alberto Piovano (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

M Residence, Mallorca, Spain, 1996-1997 (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

VL Residence, Bruges, Belgium, 1999-2000 (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

DC Residence, Waasmunster, Belguim, 1998-2001 (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

Capco Offices, Antwerp, Belgium / New York, USA, 1999-2001 (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

Copyright Bookshop, Antwerp, Belgium, 2000-2001 (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

VVD Residence, Dendermonde, Belgium, 1998-2003 (Photograph by Alberto Piovano)

Desk and Chair for Bulo, 2004 (Photography by Alberto Piovano)

Neutra Outdoor Collection for Tribù, 2008 (Photography by Alberto Piovano)

On Vincent

Vincent’s work is human;

it possesses many qualities

that we value in people.

It is calm yet determined.

It is reliable yet surprising.

It is sensual, but discreetly so.

It is sober yet spirited.

In other words, it is like a good friend,

like Vincent himself.

Ann Demeulemeester and Patrick Robyn

_

‘Verwechseln Sie bitte nicht das Einfache mit dem Simplen’

(Don’t confuse minimal with simple)

Mies van der Rohe

___

Complete Works

Vincent Van Duysen : Ilse Crawford : Marc Dubois

Thames & Hudson

2010

___

R

Maison Martin Margiela

Store in Los Angeles, Beverly Hills _ Opened on September 5th, 2007 _ Images of architectural details such as doors, stucco and moldings from Maison Martin Margiela’s former premises in Paris are are printed on transparent films

A/W 1990-91 _ Women’s show _ backstage

S/S 1990 _ Tabi boots with hand-tagged graffiti

A/W 2000-01 _ Cooperation magazine, oversized collection feature and snap shots of looks

1999 – Door sign, Boulevard Saint-Denis (headquarters of the Maison from 1990 to 1994)

A/W 2008-09 _ Women’s show, backstage

Headquarters, Paris _ Special installation in the rue Saint-Maur showroom

October 2008 _ Special and limited edition Tabi-boot shaped candle, Sent as a gift to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Maison Martin Margiela

Headquarters, Paris _ Dress forms in Martin Margiela’s studio, Boulevard Saint-Denis (headquarters of the Maison from 1990 to 1994)

S/S 2005 _ Arena Homme+ _ Line 0 _ Peter Doherty wearing a shirt printed with lipstick kisses

S/S 2007 _ Line 0 _ Invitation to the presentation of the ‘Artisanal’ collection, in the form of white embroidery on starched white cotton. It has maintained this form for every season since S/S 2006

A staff member on the stairs at the Paris headquarters, rue Saint-Maur

S/S 1998 _ View on colour _ Interview

Headquarters, Paris _ Workshop in the Maison Martin Margiela rue Saint-Maur offices

Store in Osaka _ opened on August 28th, 2003 _ Invitation and shoe display

Headquarters, Paris _ Men’s commerical showroom _ The custom made trunk and white tailors dummy’s identify the Line 14 concept: A classic and timeless wardrobe for men

The past is what binds us,

The future leads us.

___

Maison Martin Margiela

Rizzoli

2009

___

The Cult of Invisibility by Lucian James

R

The Art of Rachel Whiteread

Ghost, 1990.

Untitled (Black Bed), 1991.

Untitled (Wardrobe), 1994.

Untitled (Cast Iron Floor), 2001.

Valley, 1990.

Water Tower, 1998 – 1999.

Untitled (Amber Bed), 1991.

When referring to the specific atmosphere of a space, one often speaks metaphorically, filling it with fear, sorrow or tension. In this context, the essential presupposition is the initial emptiness of the space, which allows the viewer to fill it with something. Hardly anyone has interpreted this process as literally as the British artist Rachel Whiteread. Characterized by a certain monumentality, her sculptures push towards a chain reaction of emotional, symbolic, metaphorical, personal, and ethical/political reflections.

The viewer searches for signs to explain the vague feeling inside, tries to discover personal traces of the inhabitants in the spaces, or projects his or her own visions on or into it. Recollections, memories past and present, private and public, themes of intimacy, domestic life, childhood, loss, and death come to the fore, but the uniformity of the plaster, rubber and concrete yields nothing; blocking any sense of narrative or identity.

These spaces reveal no symbols from which one might read a personal spatial meaning or even a history. Within the solidifying of spatial volumes, the possibility of being becomes lost. The fact that the material and shape of the objects have a certain resemblance to tombstones or even mausoleums – which has been claimed repeatedly about Ghost – nourishes a feeling of permanence and finality; a feeling that can only be described as hollow.

___

The Art of Rachel Whiteread

Chris Townsend : Rachel Whiteread

Thames & Hudson

2004

___

A

Heaven and Earth | Anselm Kiefer

Studies for The Seven Heavenly Palaces, Barjac, 1973-2001

October 5, 2004 | Barjac

Michael Auping: Titling an exhibition Heaven and Earth, as we have done here, requires a little explanation. Perhaps we should just begin with the very simple question, do you believe in heaven?

Anselm Kiefer: The title Heaven and Earth is a paradox because heaven and earth don’t exist anymore. The earth is round. The cosmos has no up and down. It is moving constantly. We can no longer fix the stars to create an ideal place. This is our dilemma.

MA: And yet we keep trying to find new ways to get to ‘the ideal place’, the place we assume we came from – to find the right direction.

AK: It is natural to search for our beginnings, but not to assume it has one direction. We live in a scientific future that early philosophers and alchemists could not foresee, but they understood very fundamental relationships between heaven and earth, that we have forgotten. In the Sefer Hechaloth, the ancient book that came before the kabbala, there is no worry of directions. It describes stages, metaphors, and symbols that float everywhere. Up and down were the same direction. The Hachaloth is the spiritual journey toward perfect cognition. North, south, east, and west, up and down are not issues. For me, this also relates to time. Past, present, and future are essentially the same direction. It is about finding symbols that move in all directions.

…

MA: You are not a ‘New Age’ spiritualist. I know that for sure, but some people who see your images may wonder just what your position is in regard to religion.

AK: My spirituality is not New Age. It has been with me since I was a child. I know that in the last few decades religion has been made shiny and new. It’s like a business creating a new product. They are selling salvation. I’m not interested in being saved. I’m interested in reconstructing symbols. It’s about connecting with an older knowledge and trying to discover continuities in why we search for heaven.

MA: I can see fragments of continuity in your works between symbols that are ancient and those that take a more modern form, and for me that suggests a kind of hope within your landscapes. But there are also some very dark shadows in your images, literally in terms of color , as well as in metaphor and content. It is as if in the same image we see a liberation of knowledge but the dark weight of history.

…

MA: Christian images are apparent in your work, but in many ways not as apparent as Jewish or Gnostic references.

AK: Later, I discovered that Christian mythology was less complex and less sophisticated than Jewish mythology because the Christians limited their story to make it simple so that they could engage more people and defend their ideas. They had to fight with the Jewish traditions, with the Gnostics. It was a war of the use of knowledge. However, it wasn’t just a defense against outside ideas. It was aggressive. Like politics, they wanted to win. You know, the first church in Rome was not defensive and not aggressive. It was quiet. It was spiritual in the sense of seeking a true discussion about God. It was exploring a new idea about humanity. But then there was ‘iglesias triumphant’, the Triumph of the Church. And then the stones were stacked up and the buildings came, and the construction of the Scholastics, Augustine, and so on. They were very successful in limiting the meaning of the mythology. There were discussions about the Trinity and its meaning. anyone who had ideas that complicated their specific picture was eliminated. This made Christianity very rigid and not very interesting. Whenever knowledge becomes ridgid it stops living.

MA: In 1966, you visited the Monastery at La Tourette. Was this before you made the decision to be an artist?

AK: I began studying law. I didn’t study law to be a lawyer, but for the philosophical aspects of law, constitutional law. I was interested in how people live together with out destroying each other.

I went to La Tourette while I was studying law. It may sound strange to go from the study of law to La Tourette, but it really wasn’t. I had always been interested in law from a spiritual aspect. A constitution is not unlike the idea of a church doctrine. People need a context or a content, something to bind them together. This could be stretched to mythologies. Law, mythology, religion – they are all structures for investigating human character.

…

MA: Why did you go to La Tourette in the first place? I don’t imagine that you went only to see a Le Corbusier building. You stayed there for three weeks.

AK: The Dominicans were there. I liked their teaching. They have an interesting history. I had read that they had many discussions with Le Corbusier about the shape of the building and the materials. It was a point in my life when I wanted to think quietly about the larger questions. Churches are the stages for transmitting knowledge, interpreting knowledge and ideas of transcendence. It’s a history of conflicts and contradictions. A church is an important source of knowledge and power. Le Corbusier knew that. I stayed there for three weeks in a cell. I thought about things. In a place like that you are not simply encouraged to think about God but to think about yourself, Erkenne dich selbst. Of course, you think about your relationship to god.

Also, for me it was an inspiring building in the sense that a very simple material, a modern material, could be used to create a spiritual space. Great religions and great buildings are part of the sediment of time; like pieces of sand. Le Corbusier used the sand to construct a spiritual space. I discovered the spirituality of concrete – using earth to mould a symbol, a symbol of the imaginative and spiritual world. He tried to make heaven on earth – the ancient paradox.

…

MA: Could we go back and talk a little bit more about your education as an artist? You went to the university in Freiburg.

AK: Yes. But first I had a nineteenth-century idea that the artists is a genius – that art comes out of him naturally and he doesn’t need any education. I had always thought this, even as a child. You could say that I had too much admiration for artists. I thought they all came from heaven. Later I found out than an artwork is only partly done by the artist, that the artist is part of a larger state of things – the public, history, memory, personal history – and he must just work to find a way through it all, to remain free but connected at the same time.

…

MA: And later on you went to see Joseph Beuys, although you didn’t officially study with him.

AK: No. I was living in the forrest in Hornbach and had made some canvases. I had heard of Beuys and so I took my canvases to Düsseldorf to show him. He was impressive. I liked him very much. His dialogue was broad and he could be very impressive. He had a world view, not just the view of an artist. I think I appreciated him more because I had studied law.

MA: How so?

AK: Art cannot live on itself. It has to draw on a broader knowledge. I think both of us understood that at the tim ewe knew each other.

MA: Although I never met him, you and Beuys seem very different to me. He was more extroverted and you are more introverted, or at least less public.

AK: We were different, and as a young artist I needed to question that difference. Nevertheless, I learned a lot from him, even though he was not my teacher. I could talk to him about larger issues.

MA: In his interviews and writings, Beuys often evoked the word ‘spiritual’. How do you think he meant that?

AK: That is complicated. We were both in Germany at a certain time – a time when a dialogue about history and spirituality needed to begin. It was difficult to separate the two subjects There was a sense of starting over. To evoke the spiritual not only looking at ourselves but into the history of our nation. It was not just a matter of a critique. It had to be deeper than that. So yes, Beuys was a spiritual man. The artist is naturally spiritual because he is always searching for new beginnings.

…

MA: Here on the grounds of your home in Barjac, France, you are creating a monumental installation of stacked concrete rooms or ‘palaces’ that go up hundreds of feet into the air, asa well as a sprawling series of connected underground tunnels and spaces containing palettes, books, and lead rooms. Are you working your way through the palaces of heaven?

AK: I follow the ancient tradition of going up and going down. The palaces of heaven are still a mystery. The procedures and formulae surrounding this journey will always be debated. I am making my own investigation.

___

Heaven and Earth

Anselm Kiefer

Prestel

2005

(The catalogue is published on the occasion of the exhibition Anselm Kiefer: Heaven and Earth organized by Michael Auping for the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth)

___

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

R

Bunker Archeology | Paul Virilio

Observation post on a channel island (detail)

Observation post on a channel island (detail)

‘Barbara’ firing control tower on the Landes

‘Barbara’ firing control tower on the Landes

Observation post on a channel island

Observation post on a channel island

Observation post on a channel island

Observation post on a channel island

Observation post on the English Channel

Observation post on the English Channel

The Watten bunker – V2 launching site: the first of huge works designed to harbor stratospheric arms

The Watten bunker – V2 launching site: the first of huge works designed to harbor stratospheric arms

The ‘Todt front’: The overhung solid mass complements the vertical gradings of the embrasure

The ‘Todt front’: The overhung solid mass complements the vertical gradings of the embrasure

Observation post with flattened angles

Observation post with flattened angles

Observation tower camouflaged as church belfry

Observation tower camouflaged as church belfry

Tilting

Tilting

Sinking

Sinking

Close to death, one no longer sees it,

and you gaze steadily ahead,

perhaps with an animal’s gaze.

– R. Rilke

The discovery of the of the sea is a precious experience that bears thought. Seeing the oceanic horizon is indeed anything but a secondary experience; it is in fact an event in consciousness of underestimated consequences.

I have forgotten none of the sequences of this finding in the course of a summer when recovering peace and access to the beach were one and the same event. With the barriers removed, you were henceforth free to explore the liquid continent; the occupants had returned to their native hinterland, leaving behind, along with the work site, their tools and arms. The waterfront villas were empty, everything within the casemates’ firing range had been blown up, the beaches were mined, and the artificers were busy here and there rendering access to the sea.

The clearest feeling was still one of absence; the immense beach of La Baule was deserted, there were less than a dozen of us on the loop of blond sand, not a vehicle was to be seen on the streets; this had been a frontier that an army had just abandoned, and the meaning of this oceanic immensity was intertwined with this aspect of the deserted battlefield.

But let us get back to the sequences of my vision. The rail car I was on, and in which I had been imagining the sea, was moving slowly through the Brière plains. The weather was superb and the sky over the low ground was starting, minute by minute, to shine. This well-known brilliance of the atmosphere approaching the great reflector was totally new; the transparency I was so sensitive to was greater as the ocean got closer, up to that precise moment when a line as even as a brushstroke crossed the horizon : an almost glaucous gray-green line, but one that was extending out to the limits of the horizon. It’s color was disappointing, compared to the sky’s luminescence, but the expanse of the oceanic horizon was truly surprising: could such a vast space be void of the slightest clutter? Here was the real surprise: in length, breadth, and depth the oceanic landscape had been wiped clean. Even the sky was as divided up by clouds, but the sea seemed empty in contrast. From such a distance there was no way of determining anything like foam movement. My loss of bearings was proof that I had entered a new element; the sea had become a desert, and the August heat made that all the more evident – this was a white-hot space in which sun and ocean had become a magnifying glass scorching away every relief and contrast. Trees, pines, etched-out dark spots; the square in front of the station was at once white and void – that particular emptiness you feel in recently abandoned places. It was high noon, and the luminous verticality and liquid horizontality composed a surprising climate. Advancing in the midst of houses with gaping windows, I was anxious to set foot on my first beach. As I approached Ocean Boulevard, the water level began to rise between the pines and the villas; the ocean was getting larger, taking up more and more space in my angle of vision. Finally, while crossing the avenue parallel to the shore, the earth line seemed to have plunged into the undertow, leaving everything smooth, no waves and little noise. Yet another element was here before me: the hydrosphere.

When calling to mind the reasons that made the bunkers so appealing to me almost twenty years ago, I see it clearly now as a case of intuition and also as a convergence between the reality of the structure and the fact of its implantation alongside the ocean: a convergence between my awareness of spatial phenomena – the strong pull of the shores – and their being the locus of the works of the “Atlantic Wall” (Atlantikwall) facing the open sea, facing out into the void.

Organized by the Center for Industrial Creation and presented at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris from December 1975 through February 1976.

The pictures were taken by Paul Virilio from 1958 to 1965.

___

Bunker Archeology

Paul Virilio

Princeton Architectural Press

1994

___

R

Art Museum Bregenz | Peter Zumthor, 1990-1997

Sketch, plan

West façade with works by James Turrell on exhibit

Exterior wall

Entrance hall

Gallery space and staircase on south side

Downward view of the staircase

Gallery on upper floor

To me, there is something revealing about the work of Joseph Beuys and some of the artists of the Arte Povera group. What impresses me is the precise and sensuous ways they use materials. It seems anchored in an ancient, elemental knowledge about man’s use of materials, and at the same time to expose the very essence of these materials which is beyond all culturally conveyed meaning.

I try to use materials like this in my work. I believe that they can assume a poetic quality in the context of an architectural object, although only if the architect is able to generate a meaningful situation for them, since materials in themselves are not poetic. The sense that I try to instill into materials is beyond all rules of composition, and their tangibility, smell and acoustic qualities are merely elements of the language that we are obliged to use. Sense emerges when I succeed in bringing out the specific meanings of certain materials in my buildings, meanings which can only be perceived in just this way in just this building.

If we work towards this goal, we must constantly ask ourselves what the use of a particular material could mean in a specific architectural context. Good answers to these questions can throw new light onto both the way in which the material is generally used and its own inherent sensuous qualties.

If we succeed in this, materials in architecture can be made to shine and vibrate.

___

a+u Extra Edition| Peter Zumthor

Nobuyuki Yoshida : Peter Zumthor

a+u Publishing co.

1998

___

R

2 comments