Earth on Fire | Bernhard Edmaier

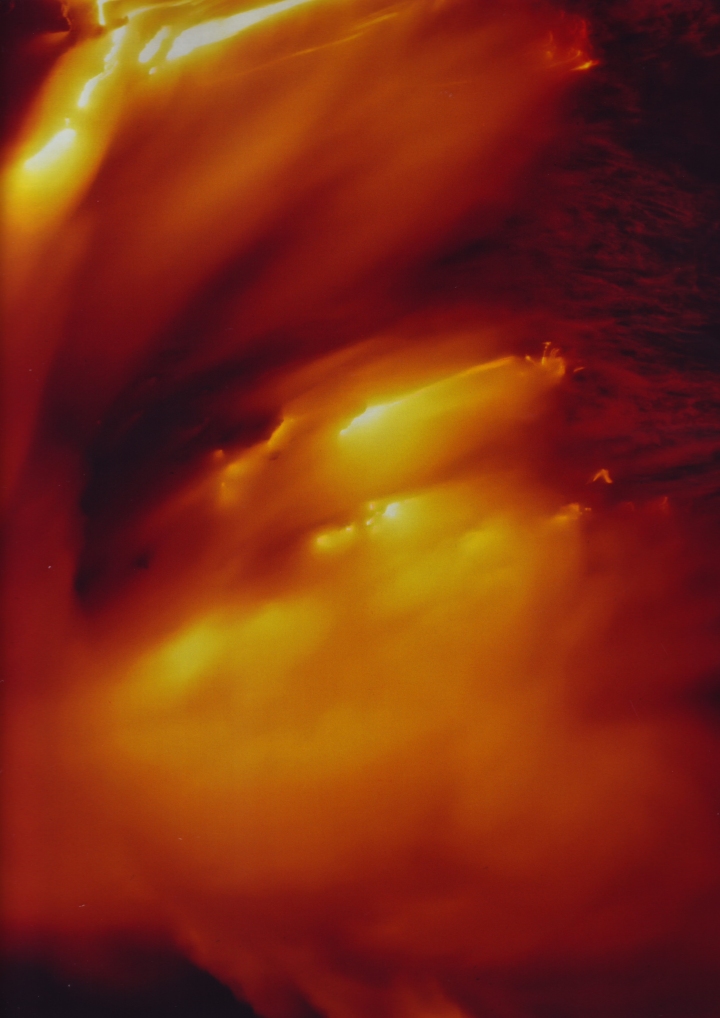

Santiaguito, Guatemala.

Kilauea (Big Island), Hawaii.

Skeiðarárjökull, Iceland.

White Island, New Zealand.

Fossa Crater (Aeolian Islands), Italy.

Erta Ale, Ethiopia.

Landeyjarsandur Estuary, Iceland.

Mount Etna, Italy.

Nyamulagira, Democratic Republic of Congo.

___

Earth on Fire

Bernhard Edmaier

Phaidon Press Inc.

2009

___

A

Himmel-Herde | Anselm Kiefer

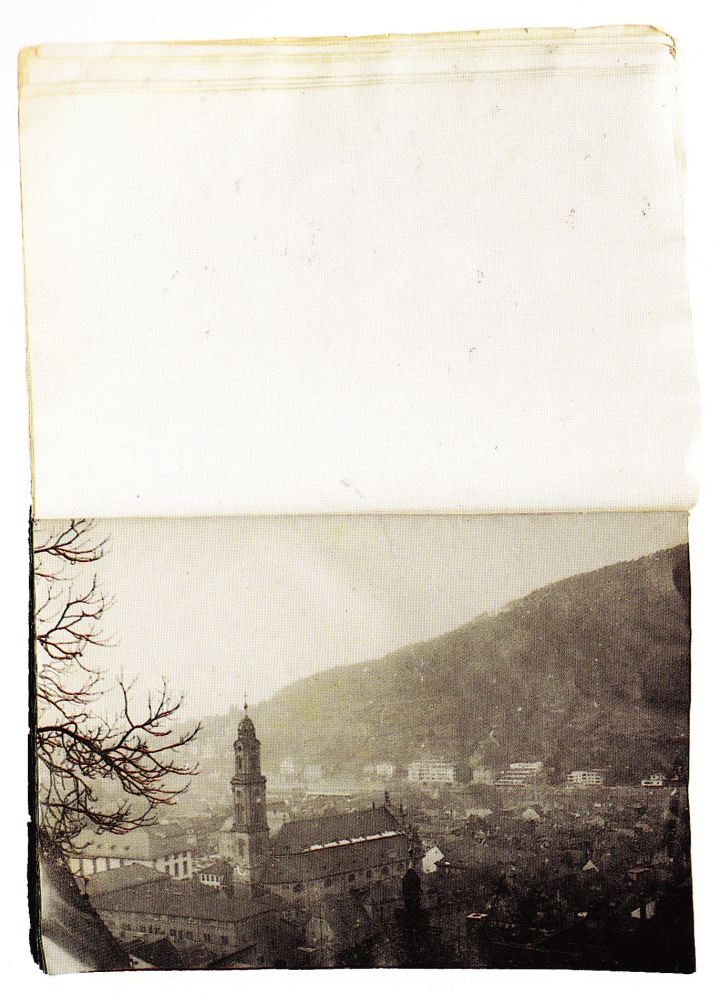

Die Überschwemmung Heidelbergs I, 1969

Die Überschwemmung Heidelbergs I, 1969

Die Überschwemmung Heidelbergs I, 1969

Die Überschwemmung Heidelbergs I, 1969

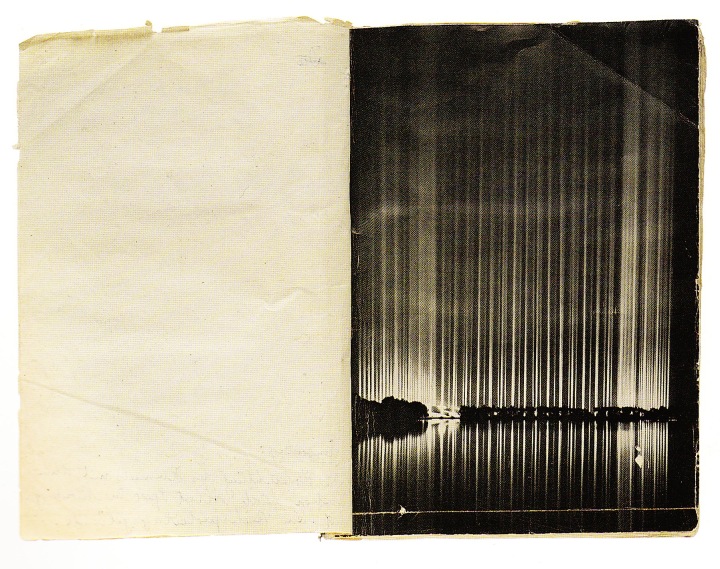

Die Himmel, 1969

Die Himmel, 1969

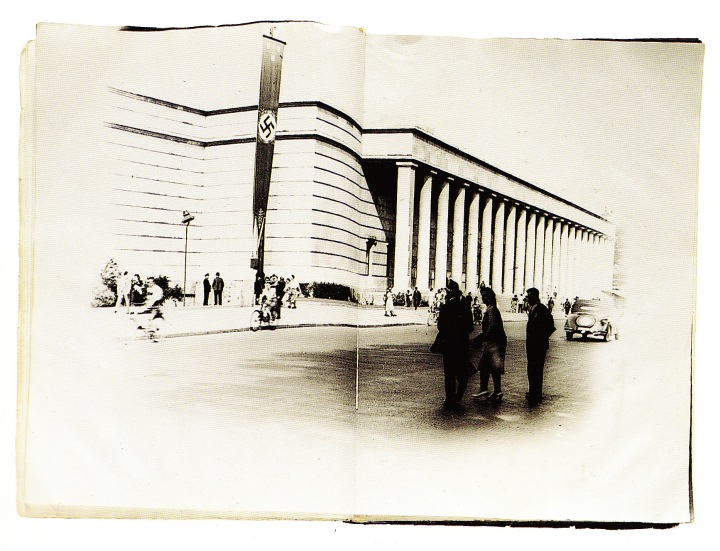

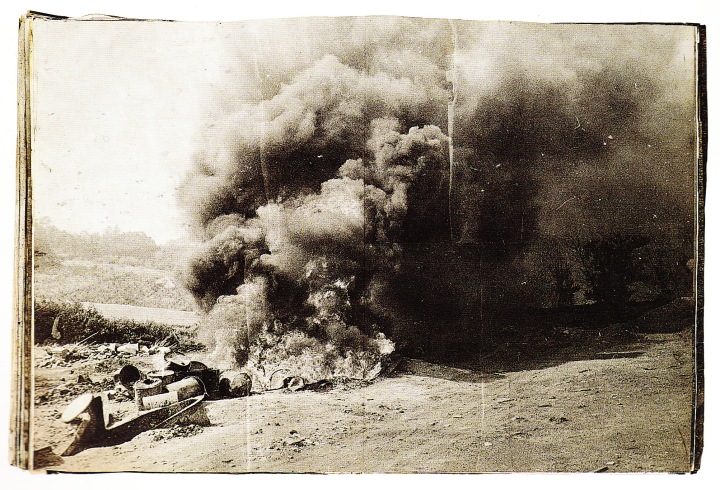

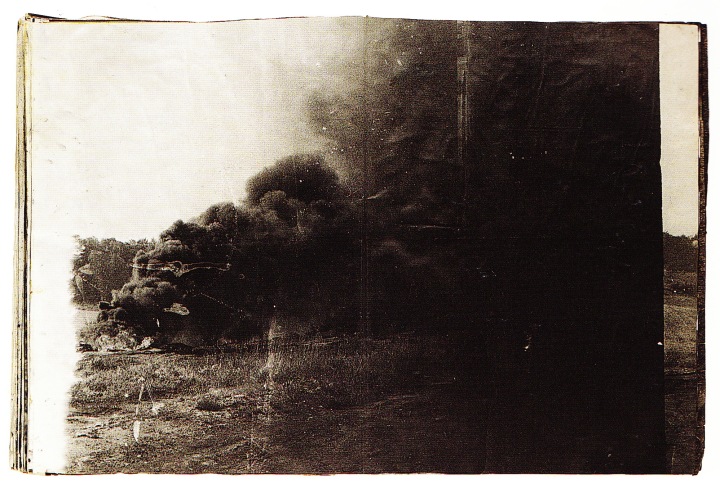

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974

Martin Heidegger, 1976

Martin Heidegger, 1976

Martin Heidegger, 1976

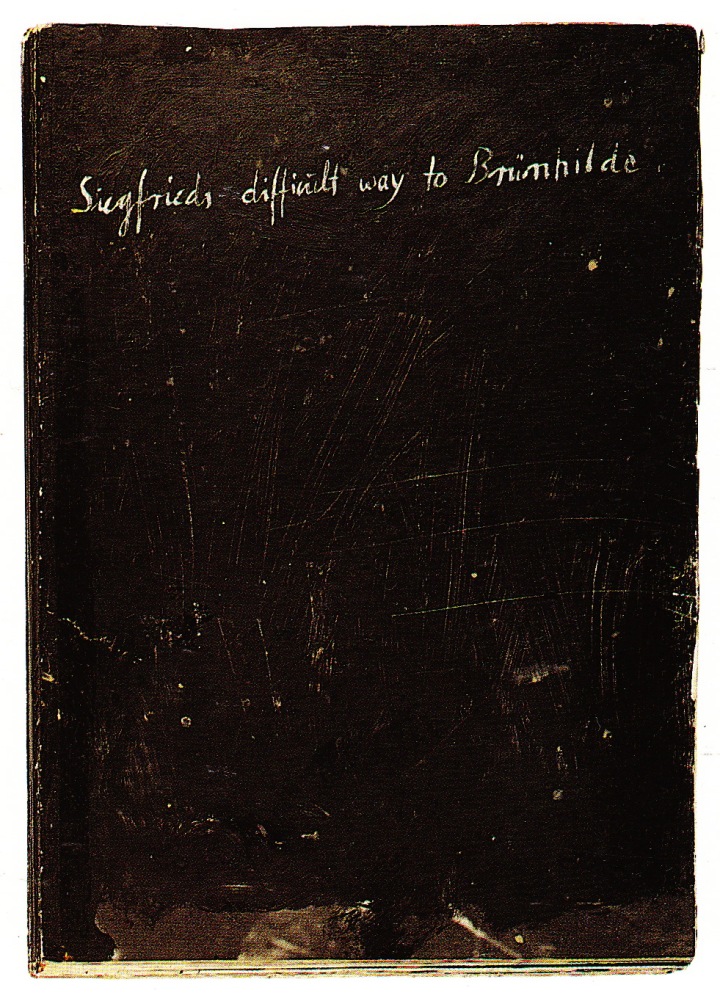

Siegfried’s Difficult Way to Brunhilde, 1977

Siegfried’s Difficult Way to Brunhilde, 1977

Siegfried’s Difficult Way to Brunhilde, 1977

Siegfried’s Difficult Way to Brunhilde, 1977

When, in order to adapt to his destiny as an artist, Anselm Kiefer attempts to throw himself open to a dimension larger than himself, he does not retreat in the face of a force that may overwhelm and daunt him. He allows himself to be possessed and swept away by it, to become the arbiter of a challenge which ultimately implies the construction of the formal energy of art. To let ourselves be overwhelmed means to agree to be impregnated and to mediate that which submerges and overtakes us: to discover ourselves in order to discover. The artist, like the poet, eludes any system, whether good or bad, religious or moral: he negates himself, dies in favour of an unknown and indefinable force, and aspires to establish the right relationship with forms and their origins. He wants to succumb to their primacy and lets himself be shattered and overwhelmed not for any banal or general reason, whether it be ideological or sociological, anonymous or impersonal, but only for one exceptional reason: the survival of the language of art.*

*The Destiny of Art: Anselm Kiefer by Germano Celant.

___

Himmel-Herde : Anselm Kiefer

Massimo Cacciari : Germano Celant : Gabriele Nason : Emanuela Belloni

Edizioni Charta

1997

___

B

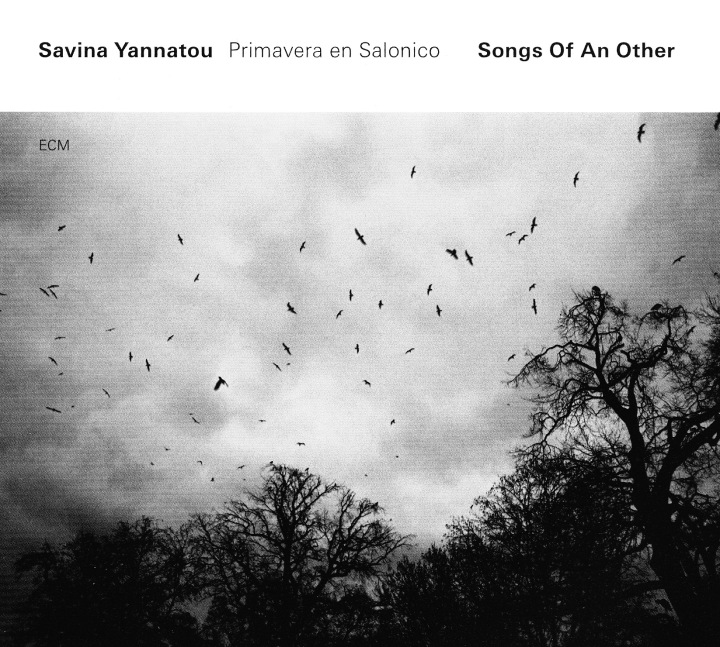

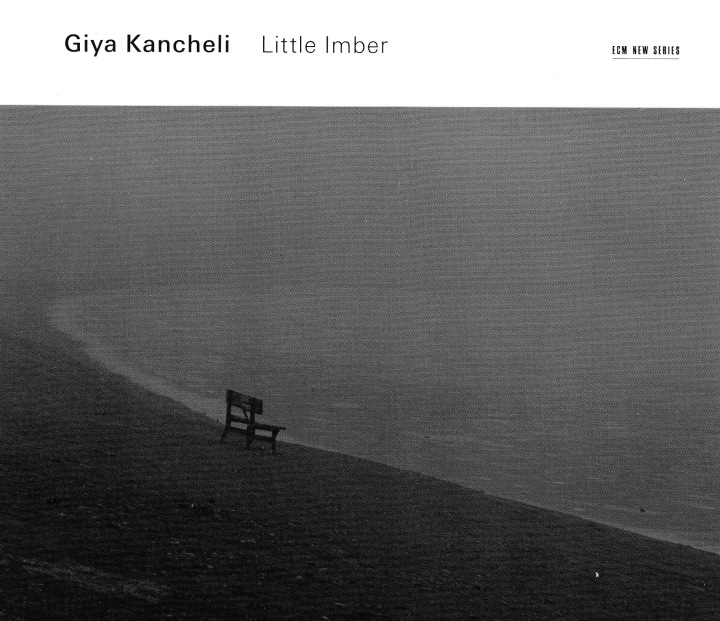

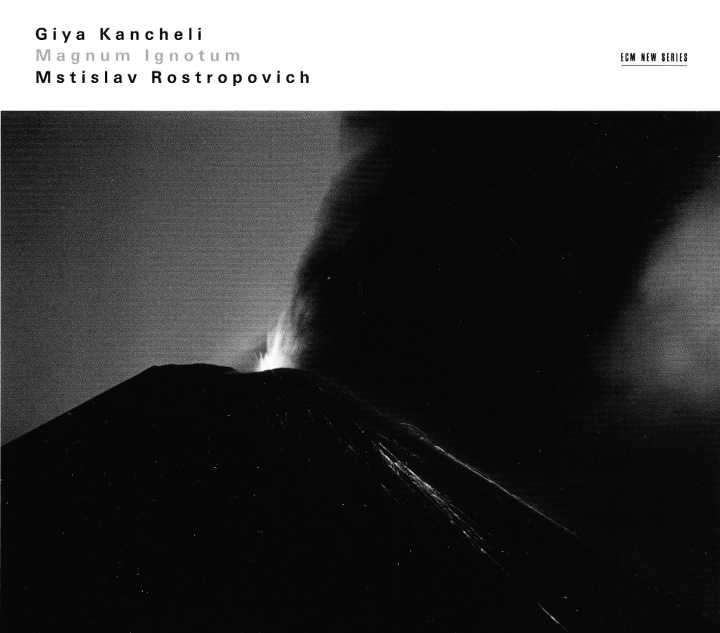

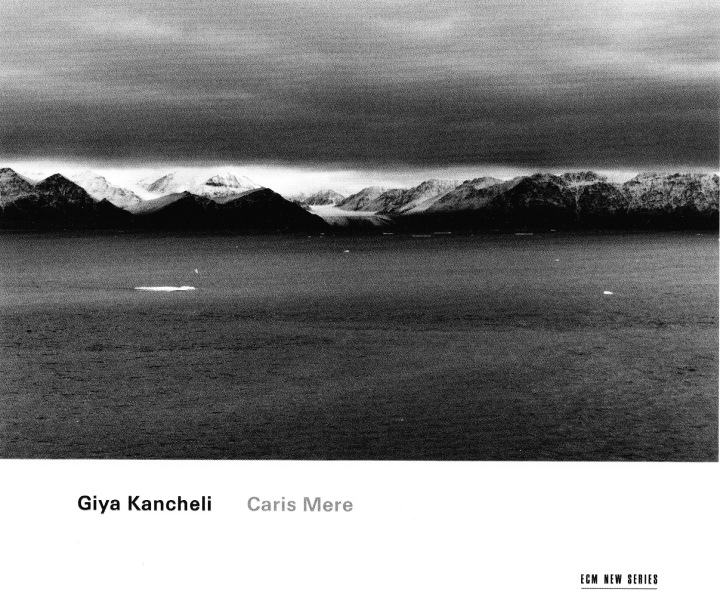

Windfall Light | The Visual Language of ECM

ECM 1979. Photograph by Christopher Egger

ECM New Series 1197. Photograph by Sarah Van Ouwekerk

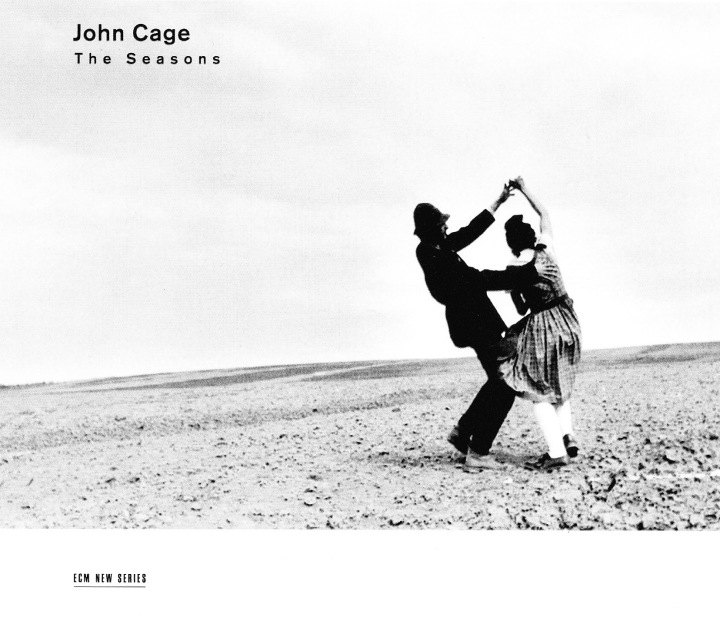

ECM 2069. Photograph by Jan Kricke

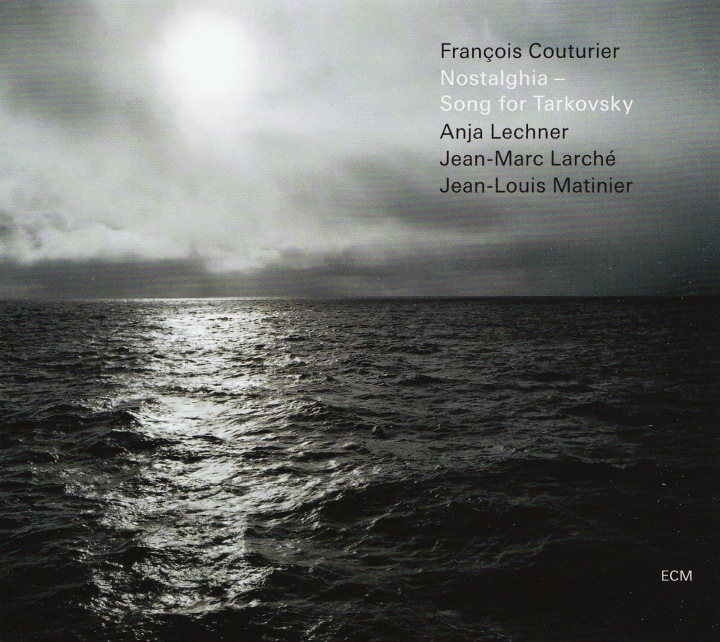

ECM 2049. Photograph by Thomas Wunsch

ECM 1964. Photograph by Thomas Wunsch

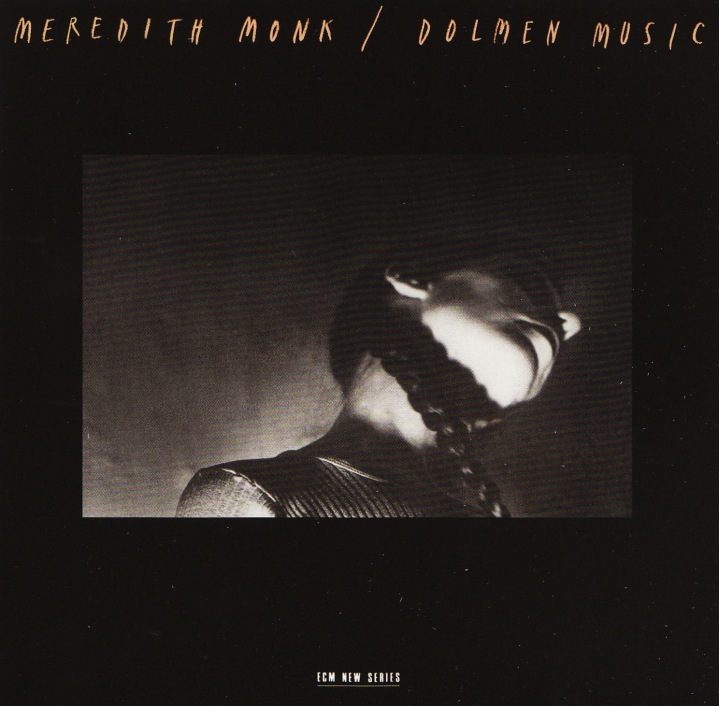

ECM New Series 1592. Art Direction by Barbara Wojirsch

ECM New Series 1696. Photograph by Jo Pessendorfer

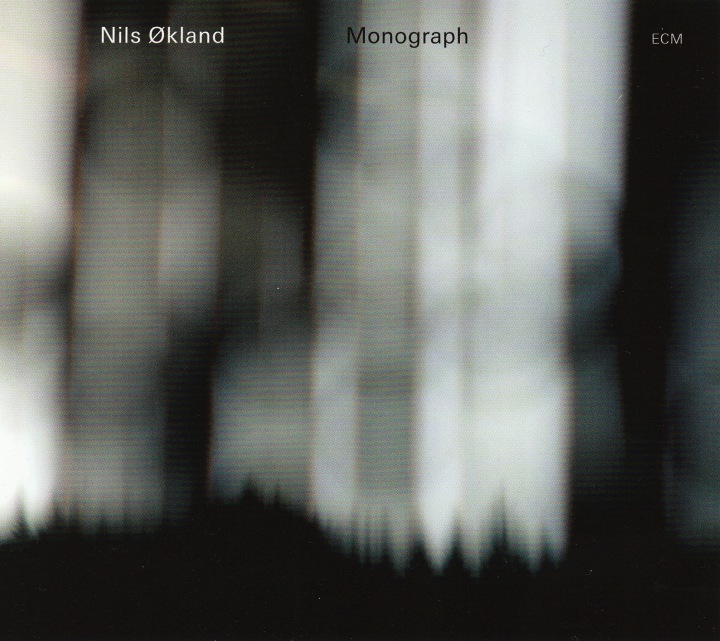

ECM 2057. Photograph by Thanos Hondros

ECM New Series 1812. Photograph by David Kvachadze

ECM New Series 1669. Photograph by Flor Garduno

ECM New Series 1568. Photograph by Christopher Egger

ECM 2073. Photograph by Sascha Kleis

ECM 1429. From: “Landscape in the Mist” by Theo Angelopoulos. Photograph by Giorgos Arvanitis

ECM 1987. Photograph by Claudine Doury

ECM New Series 1697. Photograph by Jim Bengston

ECM 2013. Photograph by Sascha Kleis

ECM 1733. Photograph by Alastair Thain

ECM 2080. Photograph by Eberhard Ross

ECM New Series 1646. Photograph by Giya Chkatavashvili

ECM New Series 2026. Photograph by John Sanchez

ECM 1664. From: “Passion” by Jean-Luc Godard

If the sea had no waves to uproot it

and give it back to the sea, if the sea had

too many waves (but not enough) to

overrun the horizon, enough (but just barely)

to disturb the earth, if the sea had no

ears to hear the sea, no eyes to be forever

the look of the sea, and if the sea had neither

salt nor foam, it would be a grey sea

of death in the sun cut off from its roots.

It would be a dying sea amid branches

cut off from the sun. It would be a mined

sea whose explosions would threaten the

world in its elephant memory. But the fruit.

What would become of the fruit? But man.

What would become of man?

-Edmond Jabès, from: The Book of Questions

___

Windfall Light : The Visual Language of ECM

Lars Müller : Thomas Steinfeld : Katharina Epprecht : Geoff Andrew : Ketil Bjørnstad

Edition of Contemporary Music : Lars Müller Publishers

2010

___

B

Do You Know What I Mean | Juergen Teller

All images; Ed in Japan, 2005/2006; originally published as Ed in Japan (Paris: Purple publications, 2006).

…It was unusual and powerful. It was clear that he was putting people in some kind of danger. There was no concern for classical beauty, but it took people somewhere else…

When Juergen starts to shoot he shoots constantly. It’s like a form of intrusion. You almost feel trapped. That’s how he manages to capture those completely uncontrolled moments because he literally traps you in his camera…

That’s how he gets those intimate moments, those unconscious movements of the body and mind. He doesn’t give you the time to organize your own mise en scène. He doesn’t give you time to think about what you are going to do. He anticipates the slightest of your movements, the slightest of your inner thoughts, and that’s how he manages to capture this incredible truth in bodies, in faces. He tries to avoid any conscious expression…

Isabelle Huppert

___

Do You Know What I Mean

Juergen Teller : Marie Darrieussecq : Isabelle Huppert

Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain / Thames & Hudson

2006

___

R

I Like America and America Likes Me | Joseph Beuys

‘For me it is the idea of the word that produces all images. It is the key sign for all forms of moulding and organizing. When I speak using a theoretical language, I try to induce the impulses of this power, the power of the whole understanding of language which for me is the spiritual understanding of evolution.’

But language is not to be understood simply in terms of speech and words. That is our current drastically reduced understanding of language, a parallel to the reduced understanding of politics and economics. Beyond language as a verbalization lies a world of sound and impulses, a language of primary sound, without semantic content, but laden with completely different levels of information.

Every form of life speaks a language, untapped and unheard.

___

Joseph Beuys : Coyote

Caroline Tisdall

Schirmer/Mosel

1976

___

R

Joseph Beuys and the Celtic World

Joseph Beuys (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Beuys completing the Brain of Europe drawing for his Hearth installation at the Royal Feldman Gallery, New York 1975 (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Beuys at Sandycove, where James Joyce lived before leaving Ireland for Europe (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Beuys investigating the plant life of Ireland, November 1974 (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Performing Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony, 1970 (photographed by Richard Demarco).

Beuys at the Giant’s Causeway, Antrim, Northern Ireland, c.1970 (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Forrest Hill Poorhouse doors, c.1980 (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Caroline Tisdall in conversation with Sean Rainbird, 2001.

Sean Rainbird: Is there a single work in the Bits and Pieces collection that has an especial importance for you?

Caroline Tisdall: There are many themes running through the collection; lots about alchemy, humour, about plants and the transformation of energy. Interconnecting Vases [Two Vases with Precious Water 1975] is probably one of the definitive images in this collection. It was made with blood and insulin, when Beuys was in hospital in 1975 following his heart attack. He was having treatment in Düsseldorf before he went to the spa in Bad Rothenfelde.

SR: So it commemorates a private event, when his health was endangered and he was physically at his most vulnerable?

CT: It is a symbol of love, friendship and reciprocity. ‘C’ and ‘D’ [Cosmas and Damian] with the cross, the triangle and, at the bottom ‘J’ and ‘C’, which could be Joseph and Caroline. The triangle is usually a trinity symbol. In all my earlier writings, I must confess I rather suppressed the Christian angle, but should acknowledge it more now. We did talk about it a lot. Fundamental to his work was the transformation of material and I think you almost have to be brought up a Catholic to use that as a creative principal.

I am a Celt and a total pagan. We often talked about spirituality. By the 1980’s he was certainly not a practicing Catholic. … But there were many elements of Catholicism he kept, like the reincarnation of souls. He also had some fundamental ideas about death and what it means as a destination. In this collection, on an ironic level, is the Hat For Next Time [1974]. After his encounter with the Dalai Lama in 1975 he was very attracted, in later life, to Buddhism. It led to the Amsterdam conference Art meets Science some years later.

It shows in his work with Nam June Paik – particularly the works with the flame. It wasn’t exclusively a Buddhist flame though; think of his saying ‘schütze die Flamme’ (guard the flame). That connects to German philosophy and produces echoes in different cultures. He was confident talking about things which were very difficult to talk about or even taboo; Braunkreuz [‘brown cross’, the distinctive brown pigment Beuys used], the German oak. He felt himself to have grown up in a Catholic, Celtic enclave [in Cleves]. The Lower Rhine is a strange spiritual place, literally quite cut off from Germany like a bend in the river.

SR: What part does language play in this?

CT: He was very deeply rooted in the German language. His whole idea of rehabilitating Germanic imagery and symbols was because he felt that any country which cannot look at its own history is built on foundations of sand and will turn more and more to modern materialism which completely denies spirituality. He felt that was really dangerous not only because of materialism, but also because of a backlash; politically, a spin back into neo-Nazism. One so wishes he had been there when Germany was reunified [in 1989] and the whole spiritual vacuum was exposed, comparing the legacy of both forms of materialism; capitalist materialism and de-spiritualised, grey, Eastern materialism.

SR: Do these sentiments come to a head in any place in Germany you visited, or in any symbolic taboos he confronted?

CT: We went to Externstein in 1975 when he was still recovering from his heart attack. It was a day trip to an absolute taboo place, as it was one of Hitler’s shrines to the Germanic spirit. All the Germanic gods were meant to be there; one of those fat fertility goddesses was dug up there. He wanted his photograph taken with his hand over his heart. What came out was a de-politicized image. It was tongue-in-cheek but like an oath-swearing gesture. He has the confidence to do that. just like the 7000 Oaks project [1982, Kassel] which was growing in his mind at the time. The oak is the symbol that you find on the Iron Cross [a military decoration]. The Nazis had really tried to subsume it into their hierarchy of symbols. As Beuys always said, it is terrible to deny the ‘oakness’ of your countryside just because of the Nazis. If you do that, you deny your own culture, your own history. In Bits and Pieces, the earliest work is an oak-leaf drawing from 1957, a collage, the earliest I have ever seen [Untitled]. I think it is an incredible drawing, so perfect. It has his old-fashioned signature, the early sort, on the bottom right.

SR: Can his use of Braunkreuz be viewed in light of your comments about national identity?

CT: The same goes for that brown colour. That terrible Nazi thing of ‘blood and earth’ [Blut und Boden]. He actually dared to take materials like that and use them, and he reinstalled them in the canon of their ‘Germanness’.

…

SR: I have always been intrigued by his use of Gothic script at certain points in his career.

CT: Gothic script has its own history. If we were German we would feel sad it fell of of use because of the Nazis. Beuys wanted to undermine the misuses and reappropriate the sources. You have to remember Heinrich Böll too, doing a huge examination of the German spirit in his writing, in books like The Lost Honour of Katharine Blum and Faces of a Clown.

SR: How well did they know one another?

CT: Beuy’s friendship with Böll was very significant. You can follow it through the decades. Böll always used to apologize for being boring! Beuys always had difficulty reading his work, of getting beyond Chapter One. They knew each other well enough for him to feel how it went on after that. The Organization for Direct Democracy through Referendum and the Free International University for Interdisciplinary Research [FIU] were both collaboration with Heinrich Böll. It was was great for Beuys to have a kindred spirit like that on his level, and vice versa…

…

SR: At what point did he intimate that he was building a collection for you. Or did it become obvious over time that this was happening?

CT: That’s a very interesting question. I’ve never thought about it. Everything with Beuys happened in such a natural way, but I imagine that by the time whole sets of things came, like the four botanical drawings Rosemary, Calendula (Marigold), Nasturtium, Pomegranate [all 1975], he was obviously building up to something. Rosemary is obviously for remembrance. And he was very fond of my mother, who was a Shakespearean actress in her younger days. And I was born in Stratford-upon-Avon. So rosemary features in the botanical things. Then calendula, which is an incredibly important homeopathic plant. When he sent it it was an amazing orange like the sun.

The collection reflects pretty accurately what was going on while it was being formed. He then actually suggested exhibiting it, and we showed it at Paul Negau’s Generative Art Gallery in 1976. By then it had its main themes: its Celtic and botanic themes, its mystical theme, alchemy and politics. The other thing there from the beginning was his interest in language: plays on words and the examinations of puns, differences between languages and curious things about English. Like the riddle in Three Hares 1975: ‘Drei Hasen und die Ohren drei und doch hat jeder seiner zwei’ (if there are three hares and three ears, how can each hare have two ears?).

…

SR: What strikes me is that it is a very practical lexicon, not a set of instructions, but a densely planted approach to someone’s art. You can read a lot of these objects very directly.

CT: Absolutely. It gives you the homeopathic, the herbal, Rudolf Steiner, biodynamics, concerns with nature as a whole, the environment, the imbalance of the spirit and the material. These run through the whole block.

SR: He seemed to have a special gift of allowing a small object to speak volumes about complex issues and projects.

CT: Take the bandage, for instance, issued to German soldiers during the war [Untitled 1977]. If you put that in a vitrine it becomes monumental; it gives you the theme of the war and a whole phase of his autobiography, and in signing such an object, he claimed it’s whole history.

…

Bits and Pieces 1957-85, [is] a rich body of objects, drawings and multiples compiled over a decade by the artist for the writer and filmmaker Caroline Tisdall. Numbering around 300 items Bits and Pieces constitutes a comprehensive lexicon of the artist’s material and ideas.

___

Joseph Beuys and the Celtic World | Scotland, Ireland and England 1970-85

Sean Rainbird

Tate Publishing

2005

___

R

Heaven and Earth | Anselm Kiefer

Studies for The Seven Heavenly Palaces, Barjac, 1973-2001

October 5, 2004 | Barjac

Michael Auping: Titling an exhibition Heaven and Earth, as we have done here, requires a little explanation. Perhaps we should just begin with the very simple question, do you believe in heaven?

Anselm Kiefer: The title Heaven and Earth is a paradox because heaven and earth don’t exist anymore. The earth is round. The cosmos has no up and down. It is moving constantly. We can no longer fix the stars to create an ideal place. This is our dilemma.

MA: And yet we keep trying to find new ways to get to ‘the ideal place’, the place we assume we came from – to find the right direction.

AK: It is natural to search for our beginnings, but not to assume it has one direction. We live in a scientific future that early philosophers and alchemists could not foresee, but they understood very fundamental relationships between heaven and earth, that we have forgotten. In the Sefer Hechaloth, the ancient book that came before the kabbala, there is no worry of directions. It describes stages, metaphors, and symbols that float everywhere. Up and down were the same direction. The Hachaloth is the spiritual journey toward perfect cognition. North, south, east, and west, up and down are not issues. For me, this also relates to time. Past, present, and future are essentially the same direction. It is about finding symbols that move in all directions.

…

MA: You are not a ‘New Age’ spiritualist. I know that for sure, but some people who see your images may wonder just what your position is in regard to religion.

AK: My spirituality is not New Age. It has been with me since I was a child. I know that in the last few decades religion has been made shiny and new. It’s like a business creating a new product. They are selling salvation. I’m not interested in being saved. I’m interested in reconstructing symbols. It’s about connecting with an older knowledge and trying to discover continuities in why we search for heaven.

MA: I can see fragments of continuity in your works between symbols that are ancient and those that take a more modern form, and for me that suggests a kind of hope within your landscapes. But there are also some very dark shadows in your images, literally in terms of color , as well as in metaphor and content. It is as if in the same image we see a liberation of knowledge but the dark weight of history.

…

MA: Christian images are apparent in your work, but in many ways not as apparent as Jewish or Gnostic references.

AK: Later, I discovered that Christian mythology was less complex and less sophisticated than Jewish mythology because the Christians limited their story to make it simple so that they could engage more people and defend their ideas. They had to fight with the Jewish traditions, with the Gnostics. It was a war of the use of knowledge. However, it wasn’t just a defense against outside ideas. It was aggressive. Like politics, they wanted to win. You know, the first church in Rome was not defensive and not aggressive. It was quiet. It was spiritual in the sense of seeking a true discussion about God. It was exploring a new idea about humanity. But then there was ‘iglesias triumphant’, the Triumph of the Church. And then the stones were stacked up and the buildings came, and the construction of the Scholastics, Augustine, and so on. They were very successful in limiting the meaning of the mythology. There were discussions about the Trinity and its meaning. anyone who had ideas that complicated their specific picture was eliminated. This made Christianity very rigid and not very interesting. Whenever knowledge becomes ridgid it stops living.

MA: In 1966, you visited the Monastery at La Tourette. Was this before you made the decision to be an artist?

AK: I began studying law. I didn’t study law to be a lawyer, but for the philosophical aspects of law, constitutional law. I was interested in how people live together with out destroying each other.

I went to La Tourette while I was studying law. It may sound strange to go from the study of law to La Tourette, but it really wasn’t. I had always been interested in law from a spiritual aspect. A constitution is not unlike the idea of a church doctrine. People need a context or a content, something to bind them together. This could be stretched to mythologies. Law, mythology, religion – they are all structures for investigating human character.

…

MA: Why did you go to La Tourette in the first place? I don’t imagine that you went only to see a Le Corbusier building. You stayed there for three weeks.

AK: The Dominicans were there. I liked their teaching. They have an interesting history. I had read that they had many discussions with Le Corbusier about the shape of the building and the materials. It was a point in my life when I wanted to think quietly about the larger questions. Churches are the stages for transmitting knowledge, interpreting knowledge and ideas of transcendence. It’s a history of conflicts and contradictions. A church is an important source of knowledge and power. Le Corbusier knew that. I stayed there for three weeks in a cell. I thought about things. In a place like that you are not simply encouraged to think about God but to think about yourself, Erkenne dich selbst. Of course, you think about your relationship to god.

Also, for me it was an inspiring building in the sense that a very simple material, a modern material, could be used to create a spiritual space. Great religions and great buildings are part of the sediment of time; like pieces of sand. Le Corbusier used the sand to construct a spiritual space. I discovered the spirituality of concrete – using earth to mould a symbol, a symbol of the imaginative and spiritual world. He tried to make heaven on earth – the ancient paradox.

…

MA: Could we go back and talk a little bit more about your education as an artist? You went to the university in Freiburg.

AK: Yes. But first I had a nineteenth-century idea that the artists is a genius – that art comes out of him naturally and he doesn’t need any education. I had always thought this, even as a child. You could say that I had too much admiration for artists. I thought they all came from heaven. Later I found out than an artwork is only partly done by the artist, that the artist is part of a larger state of things – the public, history, memory, personal history – and he must just work to find a way through it all, to remain free but connected at the same time.

…

MA: And later on you went to see Joseph Beuys, although you didn’t officially study with him.

AK: No. I was living in the forrest in Hornbach and had made some canvases. I had heard of Beuys and so I took my canvases to Düsseldorf to show him. He was impressive. I liked him very much. His dialogue was broad and he could be very impressive. He had a world view, not just the view of an artist. I think I appreciated him more because I had studied law.

MA: How so?

AK: Art cannot live on itself. It has to draw on a broader knowledge. I think both of us understood that at the tim ewe knew each other.

MA: Although I never met him, you and Beuys seem very different to me. He was more extroverted and you are more introverted, or at least less public.

AK: We were different, and as a young artist I needed to question that difference. Nevertheless, I learned a lot from him, even though he was not my teacher. I could talk to him about larger issues.

MA: In his interviews and writings, Beuys often evoked the word ‘spiritual’. How do you think he meant that?

AK: That is complicated. We were both in Germany at a certain time – a time when a dialogue about history and spirituality needed to begin. It was difficult to separate the two subjects There was a sense of starting over. To evoke the spiritual not only looking at ourselves but into the history of our nation. It was not just a matter of a critique. It had to be deeper than that. So yes, Beuys was a spiritual man. The artist is naturally spiritual because he is always searching for new beginnings.

…

MA: Here on the grounds of your home in Barjac, France, you are creating a monumental installation of stacked concrete rooms or ‘palaces’ that go up hundreds of feet into the air, asa well as a sprawling series of connected underground tunnels and spaces containing palettes, books, and lead rooms. Are you working your way through the palaces of heaven?

AK: I follow the ancient tradition of going up and going down. The palaces of heaven are still a mystery. The procedures and formulae surrounding this journey will always be debated. I am making my own investigation.

___

Heaven and Earth

Anselm Kiefer

Prestel

2005

(The catalogue is published on the occasion of the exhibition Anselm Kiefer: Heaven and Earth organized by Michael Auping for the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth)

___

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

R

Aperiatur terra | Anselm Kiefer

Palmsonntag, 2006. Mixed Media, 215 x 141 x 11 cm.

Palmsonntag, 2006. Mixed Media, 215 x 141 x 11 cm.

Palmsonntag, 2006. Mixed Media, 215 x 141 x 11 cm

Palmsonntag, 2006. Mixed Media, 215 x 141 x 11 cm.

Palmsonntag, 2006. Mixed Media, 215 x 141 x 11 cm.

Palmsonntag, 2006. Mixed Media, 215 x 141 x 11 cm.

Palmsonntag, 2006. Mixed Media, 215 x 141 x 11 cm.

A key figure in European post-war culture, Anselm Kiefer’s art derives from his great awareness of history, theology, mythology, literature and philosophy, and his exploration of a range of materials such as lead, concrete, straw, clay, flowers and seeds.

Kiefer grew up in Germany close to the French border on the Rhine and looked to France as his spiritual home. His early work was influenced by Joseph Beuys and in the context of the immediate post-war period, Kiefer set out to understand Germany’s recent history, then still a taboo subject.In later work, the artist drew on German military history, Wagnerian mythology and Nazi architecture to grapple with the possibility of pursuing creativity in the light of catastrophic human suffering. Kiefer’s technique of layering paint and debris gives visceral life to his preoccupations with decay and re-creation.

After the reunification of Germany Kiefer moved to Barjac, a small town in the South of France, developing and widening his preoccupations. His study of ancient belief-systems such as the Kabbala and travel to South America, India, China and Australia expanded his interests to a cosmic view of the world. In Barjac he was able to work on an even larger scale and confronted with the natural world, became interested in theories about the lives of plants, the microcosm and macrocosm, and the concept that for every plant there exists a correlated star. The huge installation works of Palmsonntag (Palm Sunday), refer to the Christian holy day and suggests the balance between death and resurrection, decay and recreation so characteristic of Kiefer’s work.

___

Aperiatur terra | Anselm Kiefer

Graham Howes: Anthony Bond: Norman Rosenthal

White Cube

2007

___

B

October 18, 1977 | Gerhard Richter

Arrest 1 (Festnahme 1). 1988. Oil on canvas, 92 x 126.5 cm

Confrontation 2 (Gegenüberstellung 2). 1988. Oil on canvas, 112 x 102 cm

Confrontation 3 (Gegenüberstellung 3). 1988. Oil on canvas, 112 x 102 cm

Hanged (Erhangte). 1988. Oil on canvas, 201 x 140 cm

Record Player (Plattenspieler). 1988. Oil on canvas, 62 x 83 cm

Cell (Zelle). 1988. Oil on canvas, 201 x 140 cm

Man Shot Down 2 (Erschossener 2). 1988. Oil on Canvas 100.5 x 140.5 cm

Dead (Tote). 1988, Oil on canvas, 62 x 73 cm

Funeral (Beerdigung). 1988. Oil on canvas 200 x 320 cm

In mid-winter 1989 a quiet tremor shook Germany. Judged from the outside, the extent of its impact might initially have seemed out of proportion to the actual cause. But as a long delayed aftershock and a wholly unexpected aftershock to the much greater upheavals of a decade earlier, the jolt caught people off guard, and reawakened deep-seated, intensely conflicted emotions.

The epicenter of this event was in Krefeld, a small Rhineland city near Cologne where, between February 12 and April 4, 1989, a group of fifteen austere grey paintings were exhibited at Haus Esters, a local museum designed in 1927-30 as a private residence by the modernist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The author of these works was the then fifty seven year old painter Gerhard Richter, well known for the heterogeneous and enigmatic nature of his art, which ranged from postcard-pretty landscapes to minimal grids, alternatively taut or churning monochromes to crisp colour charts, and heavily textured, even garish, abstractions to cool black-and-white photo based images. The ensemble on view at Haus Esters belonged to the latter genre, which had preoccupied Richter from the outset of his career in 1962 until 1972 but which he had seemed to abandon since then. However the subject of the new paintings was unlike anything he had addressed before. Both the subject and the fact that an artist of Richter’s indisputable stature had chosen to paint it stirred Germany and, in short order, sent reverberations around the world.

Richter’s theme was the controversial lives and deaths of four German social activists turned terrorists: Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, Holger Meins and Ulrike Meinhof. The collective title, October 18, 1977, commemorates the day the bodies of Baader and Ensslin – along with their comrades, the dying Jan-Carl Raspe and the wounded Irmgard Möller – were discovered in their cells at the high-security prison in Stammheim, near Stuttgart, where they had been incarcerated during and after their trials for murder and other politically motivated crimes. Almost exactly three years earlier (October 2, 1972) Holger Meins had died from starvation during a hunger strike called by the jailed radicals to protest prison conditions. Ulrike Meinhof had been found hanging in her Stammheim cell (May 9, 1976) shortly before she and the others were sentenced to life terms. Her death was ruled as suicide as were those of Baader, Ensslin, and Raspe the following year (October 18, 1977), although there was widespread suspicion that the four had been murdered.

___

October 18, 1977 | Gerhard Richter

Robert Storr

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

2000

___

October 18, 1977, Museum of Modern Art, New York

B

5 comments