How It Is | Miroslaw Balka

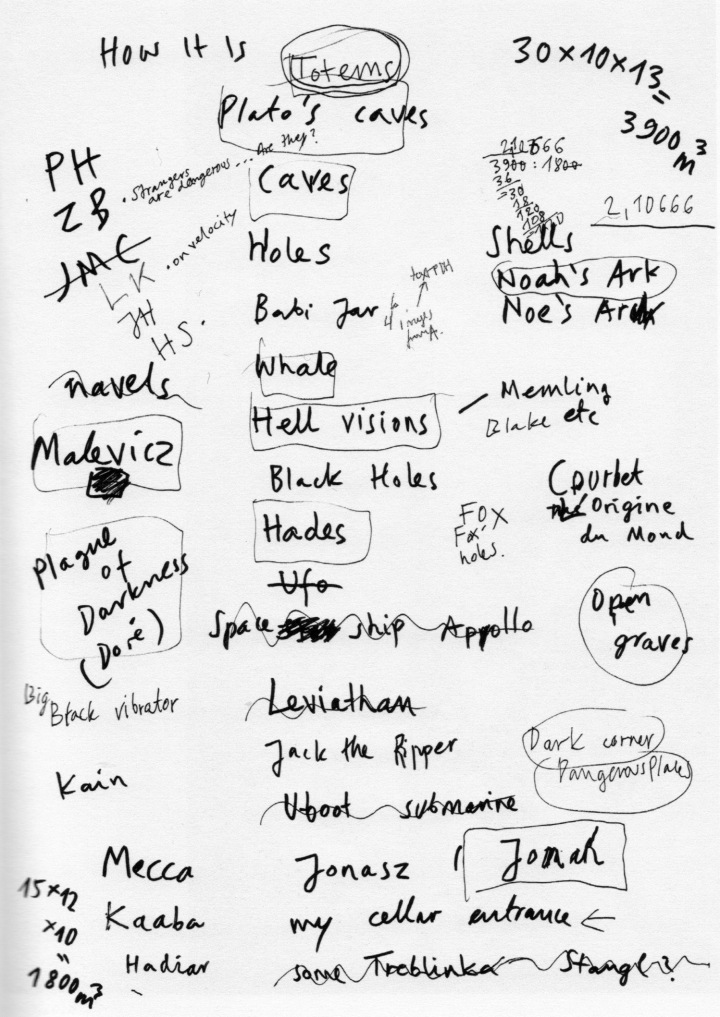

List of references for How It Is, April 2009

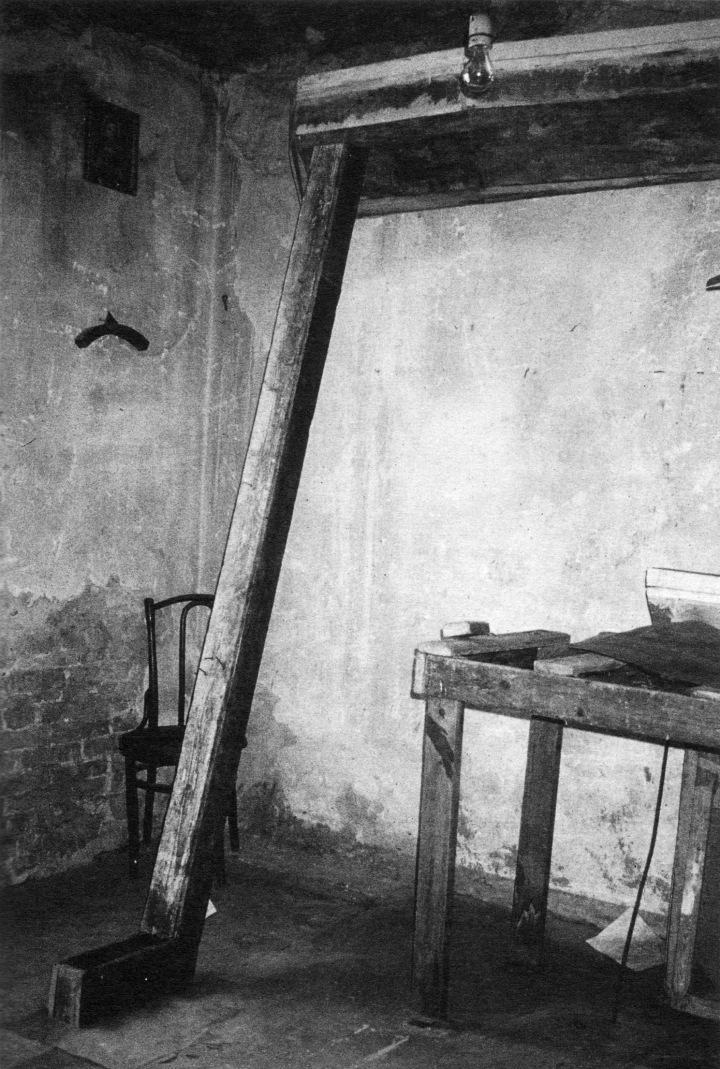

The artist’s studio with elements of Oasis (CDF), 1989

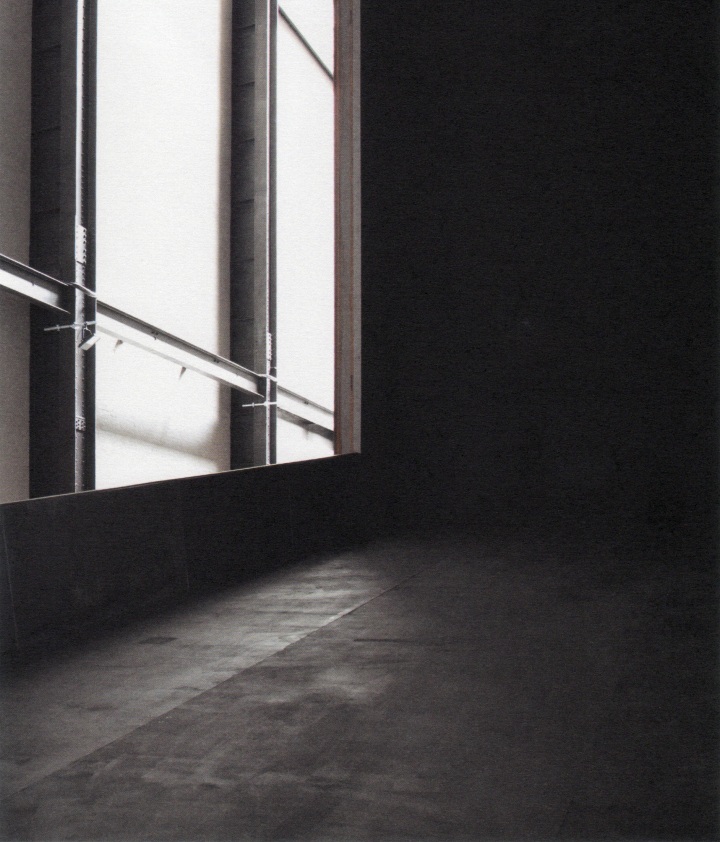

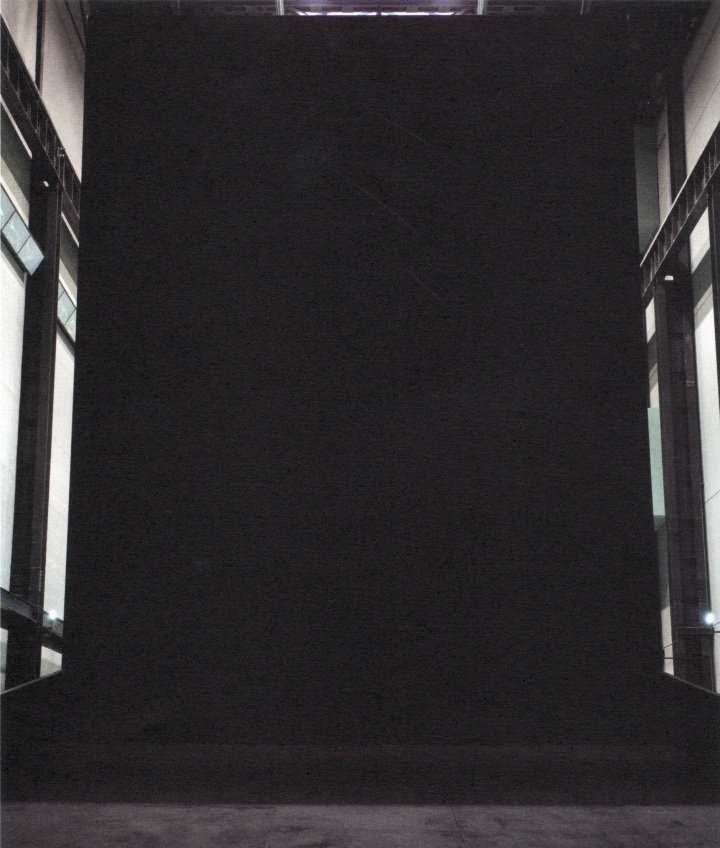

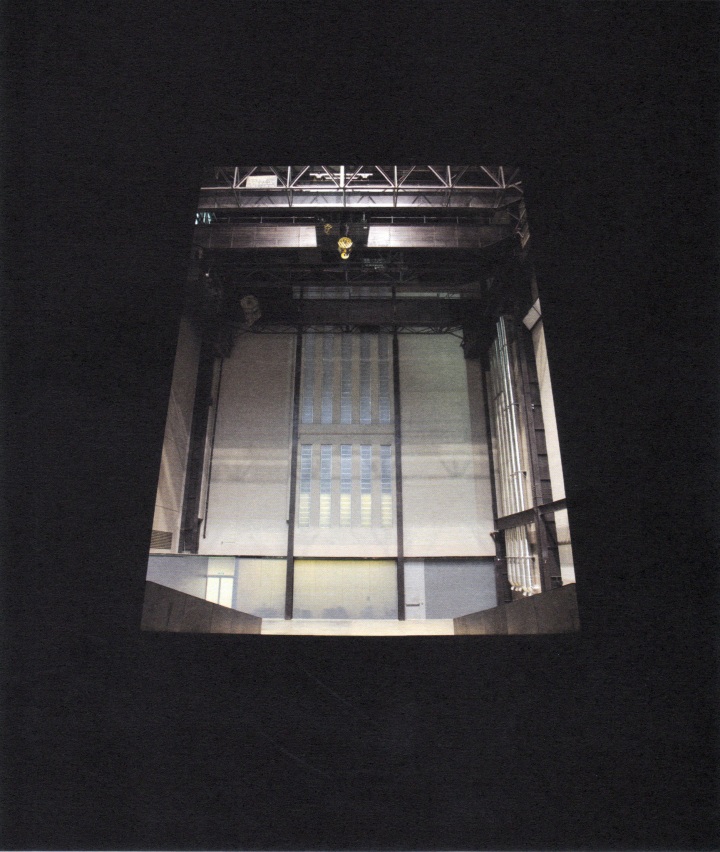

How It Is, 2009 (photography by Sam Irons)

Ancient myths and the pictures of the modern era that are based on these present the domain of Hades – the shadowy realm of the dead or literally darkness, that which we cannot perceive – a place filled with a multitude of terrors. However, it is not portrayed as just another place, as the negative of this world. Particular importance also attaches to the path to Hades, the path into the underworld marked out by the travelers arrival at the river Styx, separating our world from the next, the crossing of the styx in Charon’s barque, and the moment of appearing before the god Hades. The theological, philosophical and psychological meanings of this and other descriptions of this path into death are self-evident. Of necessity they resort to recognizable metaphors to explain something that has never been seen or understood. Real burial grounds, for instance those of the Ancient Egyptians or Neolithic man in Britain, also pay particular attention to the passage from this world to the next, where effort is required to make the journey from light into complete darkness. It is only relatively recently that Balka first contemplated this zone in his work, although there are earlier shades of it here and there that dissipate into the muted twilight that pervades most of his videos. More often darkness is indirectly evoked by somewhat weak lights. Later on, when he coats the walls of the exhibition space with a two-and-a-half-meter high, continuous layer of ash, or makes a long, narrow walkway with twists and turns from simple timber, although he may literally and metaphorically be working his way toward darkness, these pieces are presented in full light of the exhibition space. No so in the case of How It Is. As the viewer approaches, it looks like a huge container, a mighty sculpture with a powerful presence. However, walking round it brings one to something else entirely, and to a sudden halt. A fragment of memory: turning the pages of the philosopher Robert Fludd’s magnum opus of 1617 the readers may find, to their surprise, a large black square taking up much of page twenty-six. ‘Et sic in infinitum’ is inscribed into all four margins of the dark square: ‘And this into infinity’, a something that one cannot imagine. The non-picture comes at the beginning of a chapter about shadows and privatio, a word that translates as both ‘privation’ and ‘liberation’. Cut. The back wall of the colossal container has been lowered, forming a ramp into the darkness. What wonder or beats await us inside? Will we have the curiosity and calm determination of János in Béla Tarr’s movie Werckmeister Harmonies to pursue the unknown, in astonishment, or will we gaze at it from the outside, uninvolved and suspicious? The steel room is large enough for its depths to be shrouded in mystery as we enter, but it is also wide enough to move about freely inside it – alone or with others. It is not pitch black inside, just increasingly dark; turning around we can still see the outside. The mise-en-scene of the unknown is overwhelming, but not because the Turbine Hall where it is placed would dwarf any smaller structure. The fact is that might raised up steel body – as tall as a house – corresponds in size to our inner sense of the unknown, of the limits of life. The effort and huge amount of material that went into making it were necessary to convey the notion, the fear, the black block that weighs us down on the last path. The sculpture had to become almost absurdly large in order to give a true sense of the threat that looms at us in the shape of the last wall in the realms of our imagination. However, when one in fact enters the black box, there is no climax to this sense of the overwhelmingly uncanny, instead there is a kind of gradual dis-illusion as one becomes accustomed to the darkness, an insight into ‘how it is’. Privatio: deprived of the certainty of life yet also liberated from the fear? The black container is a paradox. It has the dimensions of fear and is large enough to accommodate a social event, but it also has the intimacy of an individual thought and the normality of a single life.

Julian Heynen (Translated by Fiona Elliott)

___

How It Is

Miroslaw Balka : Zygmut Bauman : Julian Heyene : Paulo Herkenhoff : László Krasznahorkai : Helen Sainsbury

Tate Publishing

2009

___

Tate Channel: The Unilever Series: Miroslaw Balka

R

Joseph Beuys and the Celtic World

Joseph Beuys (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Beuys completing the Brain of Europe drawing for his Hearth installation at the Royal Feldman Gallery, New York 1975 (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Beuys at Sandycove, where James Joyce lived before leaving Ireland for Europe (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Beuys investigating the plant life of Ireland, November 1974 (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Performing Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony, 1970 (photographed by Richard Demarco).

Beuys at the Giant’s Causeway, Antrim, Northern Ireland, c.1970 (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Forrest Hill Poorhouse doors, c.1980 (photographed by Caroline Tisdall).

Caroline Tisdall in conversation with Sean Rainbird, 2001.

Sean Rainbird: Is there a single work in the Bits and Pieces collection that has an especial importance for you?

Caroline Tisdall: There are many themes running through the collection; lots about alchemy, humour, about plants and the transformation of energy. Interconnecting Vases [Two Vases with Precious Water 1975] is probably one of the definitive images in this collection. It was made with blood and insulin, when Beuys was in hospital in 1975 following his heart attack. He was having treatment in Düsseldorf before he went to the spa in Bad Rothenfelde.

SR: So it commemorates a private event, when his health was endangered and he was physically at his most vulnerable?

CT: It is a symbol of love, friendship and reciprocity. ‘C’ and ‘D’ [Cosmas and Damian] with the cross, the triangle and, at the bottom ‘J’ and ‘C’, which could be Joseph and Caroline. The triangle is usually a trinity symbol. In all my earlier writings, I must confess I rather suppressed the Christian angle, but should acknowledge it more now. We did talk about it a lot. Fundamental to his work was the transformation of material and I think you almost have to be brought up a Catholic to use that as a creative principal.

I am a Celt and a total pagan. We often talked about spirituality. By the 1980’s he was certainly not a practicing Catholic. … But there were many elements of Catholicism he kept, like the reincarnation of souls. He also had some fundamental ideas about death and what it means as a destination. In this collection, on an ironic level, is the Hat For Next Time [1974]. After his encounter with the Dalai Lama in 1975 he was very attracted, in later life, to Buddhism. It led to the Amsterdam conference Art meets Science some years later.

It shows in his work with Nam June Paik – particularly the works with the flame. It wasn’t exclusively a Buddhist flame though; think of his saying ‘schütze die Flamme’ (guard the flame). That connects to German philosophy and produces echoes in different cultures. He was confident talking about things which were very difficult to talk about or even taboo; Braunkreuz [‘brown cross’, the distinctive brown pigment Beuys used], the German oak. He felt himself to have grown up in a Catholic, Celtic enclave [in Cleves]. The Lower Rhine is a strange spiritual place, literally quite cut off from Germany like a bend in the river.

SR: What part does language play in this?

CT: He was very deeply rooted in the German language. His whole idea of rehabilitating Germanic imagery and symbols was because he felt that any country which cannot look at its own history is built on foundations of sand and will turn more and more to modern materialism which completely denies spirituality. He felt that was really dangerous not only because of materialism, but also because of a backlash; politically, a spin back into neo-Nazism. One so wishes he had been there when Germany was reunified [in 1989] and the whole spiritual vacuum was exposed, comparing the legacy of both forms of materialism; capitalist materialism and de-spiritualised, grey, Eastern materialism.

SR: Do these sentiments come to a head in any place in Germany you visited, or in any symbolic taboos he confronted?

CT: We went to Externstein in 1975 when he was still recovering from his heart attack. It was a day trip to an absolute taboo place, as it was one of Hitler’s shrines to the Germanic spirit. All the Germanic gods were meant to be there; one of those fat fertility goddesses was dug up there. He wanted his photograph taken with his hand over his heart. What came out was a de-politicized image. It was tongue-in-cheek but like an oath-swearing gesture. He has the confidence to do that. just like the 7000 Oaks project [1982, Kassel] which was growing in his mind at the time. The oak is the symbol that you find on the Iron Cross [a military decoration]. The Nazis had really tried to subsume it into their hierarchy of symbols. As Beuys always said, it is terrible to deny the ‘oakness’ of your countryside just because of the Nazis. If you do that, you deny your own culture, your own history. In Bits and Pieces, the earliest work is an oak-leaf drawing from 1957, a collage, the earliest I have ever seen [Untitled]. I think it is an incredible drawing, so perfect. It has his old-fashioned signature, the early sort, on the bottom right.

SR: Can his use of Braunkreuz be viewed in light of your comments about national identity?

CT: The same goes for that brown colour. That terrible Nazi thing of ‘blood and earth’ [Blut und Boden]. He actually dared to take materials like that and use them, and he reinstalled them in the canon of their ‘Germanness’.

…

SR: I have always been intrigued by his use of Gothic script at certain points in his career.

CT: Gothic script has its own history. If we were German we would feel sad it fell of of use because of the Nazis. Beuys wanted to undermine the misuses and reappropriate the sources. You have to remember Heinrich Böll too, doing a huge examination of the German spirit in his writing, in books like The Lost Honour of Katharine Blum and Faces of a Clown.

SR: How well did they know one another?

CT: Beuy’s friendship with Böll was very significant. You can follow it through the decades. Böll always used to apologize for being boring! Beuys always had difficulty reading his work, of getting beyond Chapter One. They knew each other well enough for him to feel how it went on after that. The Organization for Direct Democracy through Referendum and the Free International University for Interdisciplinary Research [FIU] were both collaboration with Heinrich Böll. It was was great for Beuys to have a kindred spirit like that on his level, and vice versa…

…

SR: At what point did he intimate that he was building a collection for you. Or did it become obvious over time that this was happening?

CT: That’s a very interesting question. I’ve never thought about it. Everything with Beuys happened in such a natural way, but I imagine that by the time whole sets of things came, like the four botanical drawings Rosemary, Calendula (Marigold), Nasturtium, Pomegranate [all 1975], he was obviously building up to something. Rosemary is obviously for remembrance. And he was very fond of my mother, who was a Shakespearean actress in her younger days. And I was born in Stratford-upon-Avon. So rosemary features in the botanical things. Then calendula, which is an incredibly important homeopathic plant. When he sent it it was an amazing orange like the sun.

The collection reflects pretty accurately what was going on while it was being formed. He then actually suggested exhibiting it, and we showed it at Paul Negau’s Generative Art Gallery in 1976. By then it had its main themes: its Celtic and botanic themes, its mystical theme, alchemy and politics. The other thing there from the beginning was his interest in language: plays on words and the examinations of puns, differences between languages and curious things about English. Like the riddle in Three Hares 1975: ‘Drei Hasen und die Ohren drei und doch hat jeder seiner zwei’ (if there are three hares and three ears, how can each hare have two ears?).

…

SR: What strikes me is that it is a very practical lexicon, not a set of instructions, but a densely planted approach to someone’s art. You can read a lot of these objects very directly.

CT: Absolutely. It gives you the homeopathic, the herbal, Rudolf Steiner, biodynamics, concerns with nature as a whole, the environment, the imbalance of the spirit and the material. These run through the whole block.

SR: He seemed to have a special gift of allowing a small object to speak volumes about complex issues and projects.

CT: Take the bandage, for instance, issued to German soldiers during the war [Untitled 1977]. If you put that in a vitrine it becomes monumental; it gives you the theme of the war and a whole phase of his autobiography, and in signing such an object, he claimed it’s whole history.

…

Bits and Pieces 1957-85, [is] a rich body of objects, drawings and multiples compiled over a decade by the artist for the writer and filmmaker Caroline Tisdall. Numbering around 300 items Bits and Pieces constitutes a comprehensive lexicon of the artist’s material and ideas.

___

Joseph Beuys and the Celtic World | Scotland, Ireland and England 1970-85

Sean Rainbird

Tate Publishing

2005

___

R

2 comments