A Question of Faith | Colin McCahon

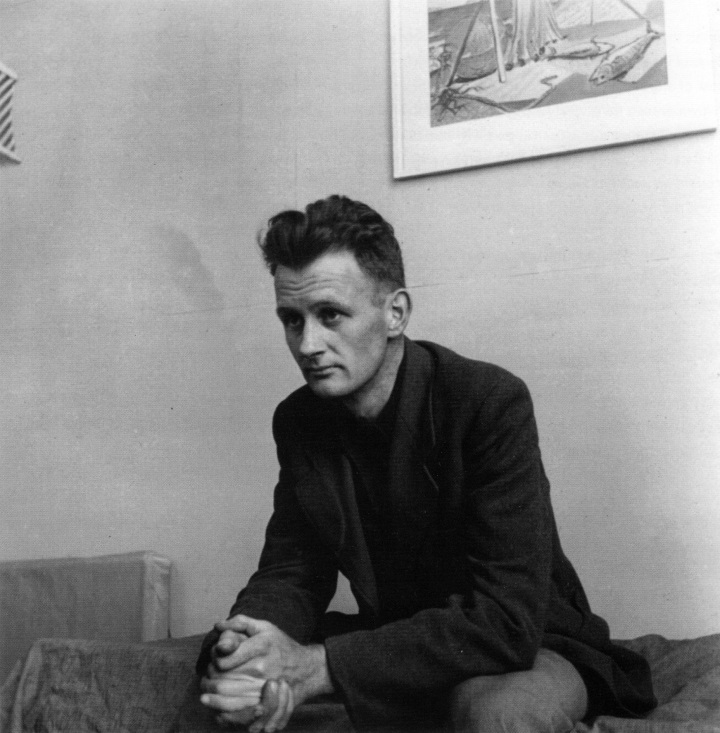

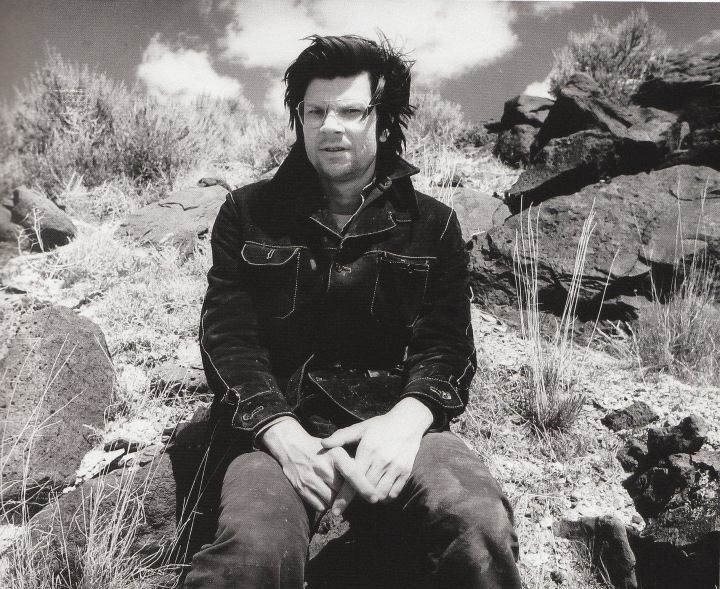

Colin McCahon, c. 1950. Courtesy of the Doris Lusk Estate.

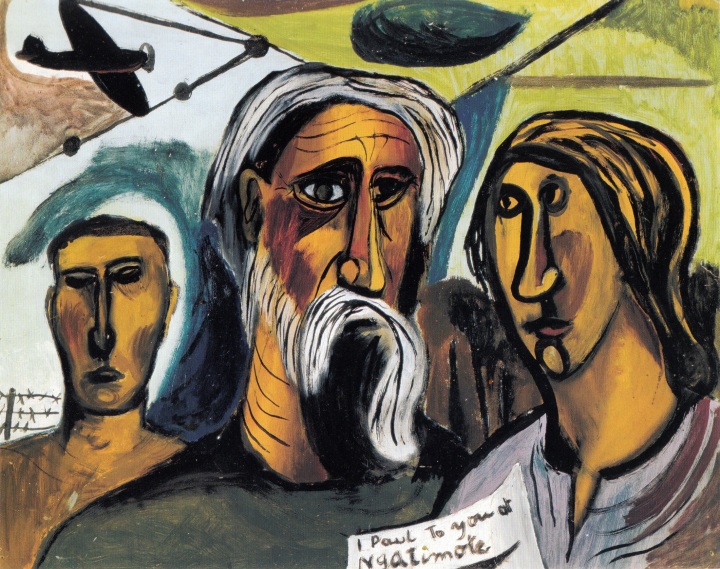

I Paul to you at Ngatimote, 1946.

Oil on cardboard, 50.5 x 63.5 cm.

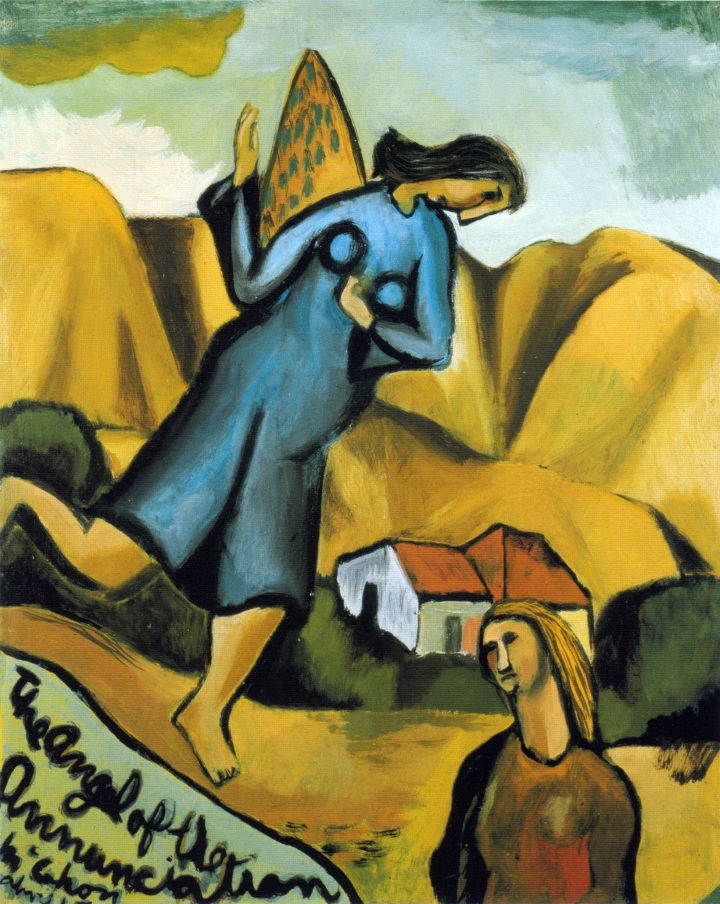

The Angel of the Annunciation, 1947.

Oil on cardboard, 63.5 x 51.2 cm.

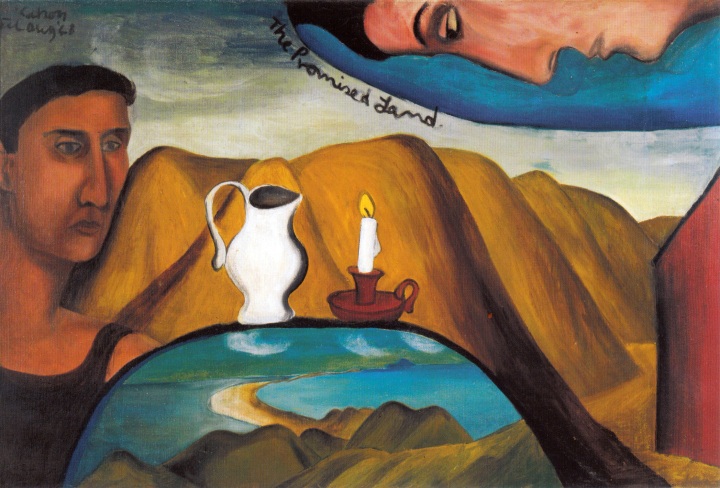

The Promised Land, 1948.

Oil on canvas, 92 x 137 cm.

The King of the Jews, 1947.

Oil on cardboard mounted on hardboard, 63.6 x 52 cm.

North Otago Landscape, 1951.

Oil on canvas on board, 51.5 x 66.2 cm.

Six days in Nelson and Canterbury, 1950.

Oil on canvas laid on board, 88.5 x 116.5 cm.

Cross, 1959.

Enamel on hardboard, 121.9 x 76.2 cm.

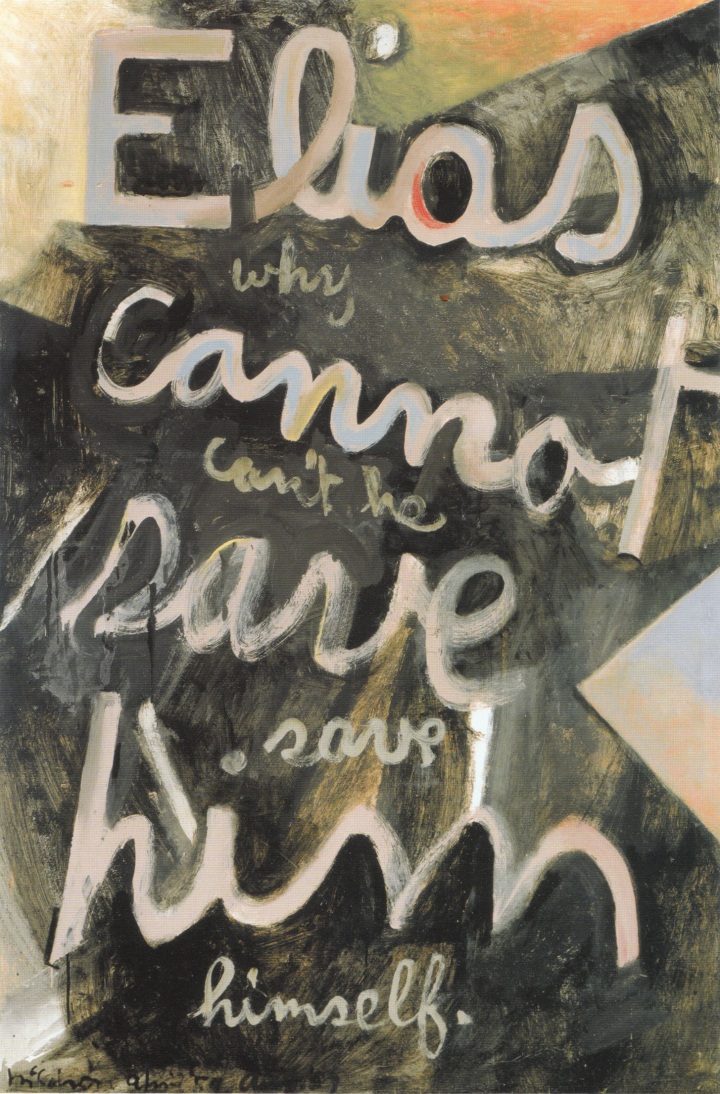

Elias: why can’t He save Himself (Elias series), 1959.

Enamel and sawdust on hardboard, 147.5 x 100 cm.

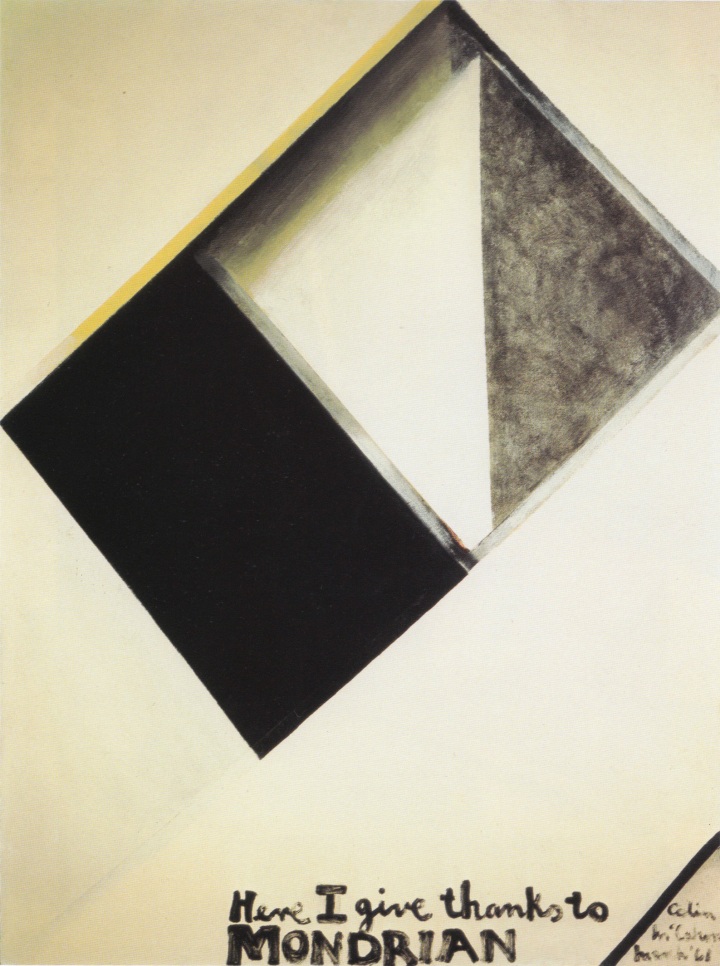

Here I give thanks to Mondrian, 1961.

Enamel on hardboard, 121.8 x 91.4 cm.

![095 Waterfall [one panel from a polytych], 1964](https://historyofourworld.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/095-waterfall-one-panel-from-a-polytych-1964.jpg?w=720&h=1701)

Waterfall [one panel from a polytych], 1964.

Enamel on plywood panel, 212.7 x 90.5 cm.

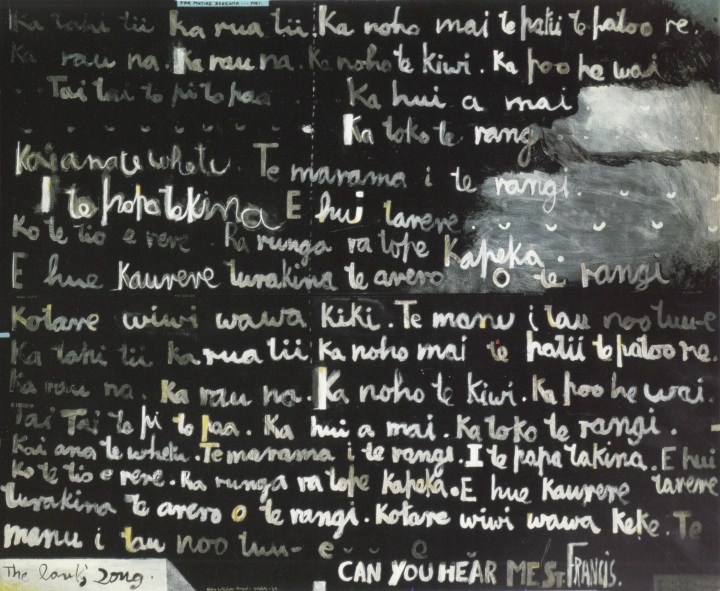

The Lark’s Song (a poem by Matire Kereama), 1969.

Acrylic on two wooden doors, overall 162.6 x 198 cm.

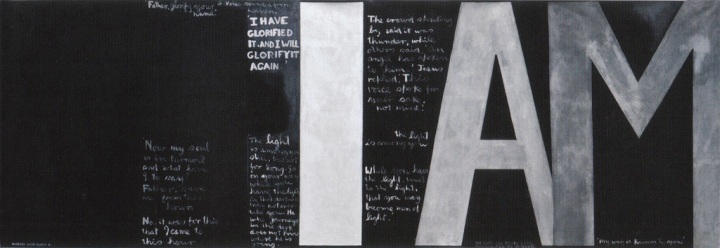

Victory over Death 2, 1970.

Acrylic on unstretched canvas, 207.5 x 597.7 cm.

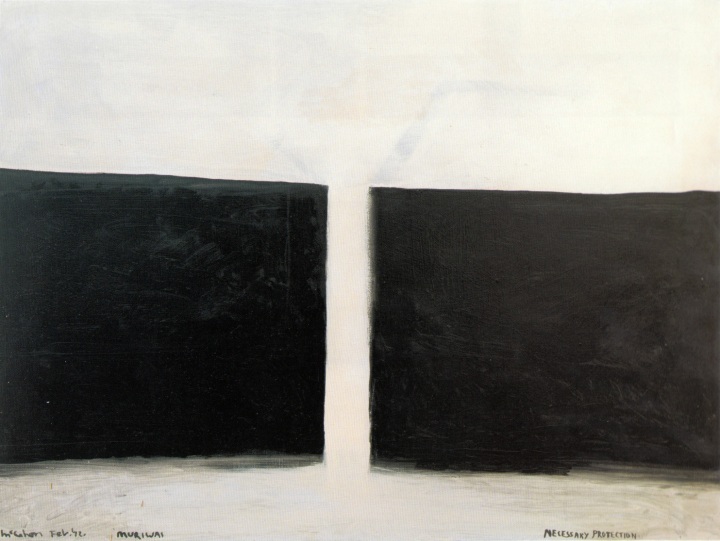

Muriwai. Necessary Protection, 1972.

Acrylic on hardboard, 60.8 x 81.2 cm.

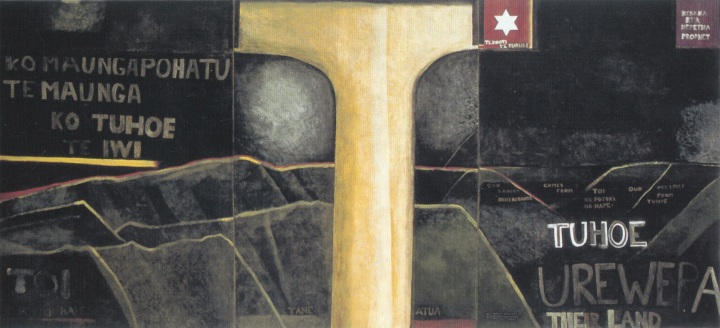

Urewera Mural, 1975.

Acrylic on three unstretched canvases, overall 255 x 544.5 cm.

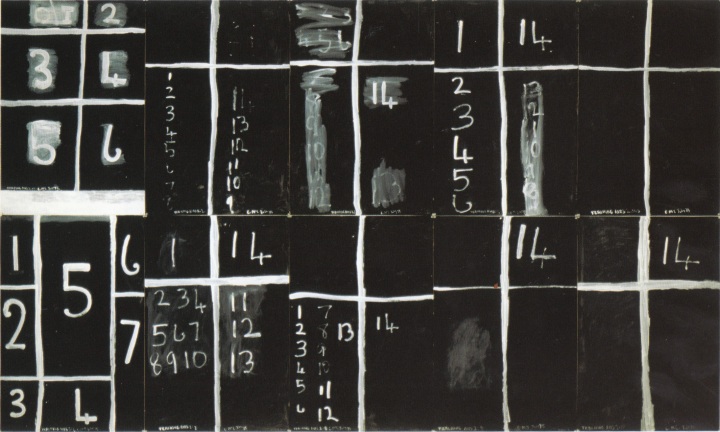

Teaching Aids 2 (July), 1975.

Acrylic on Steinbach paper, 10 sheets, each 109.2 x 72.8 cm, overall size 218.4 x 364 cm.

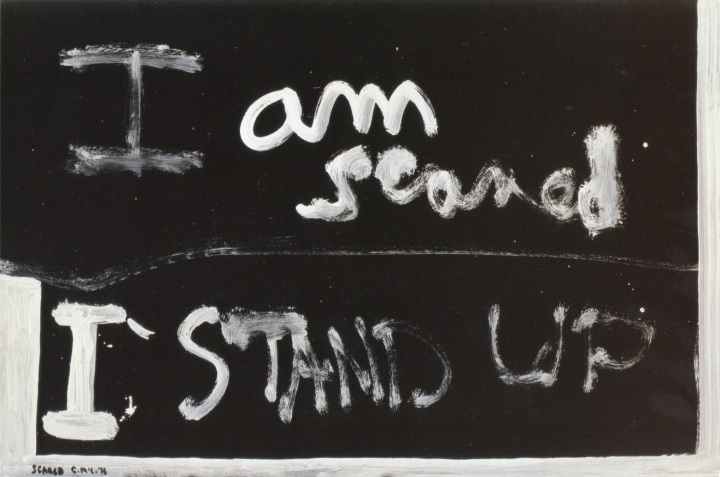

Scared, 1976.

Acrylic on Steinbach paper, 71.5 x 107 cm.

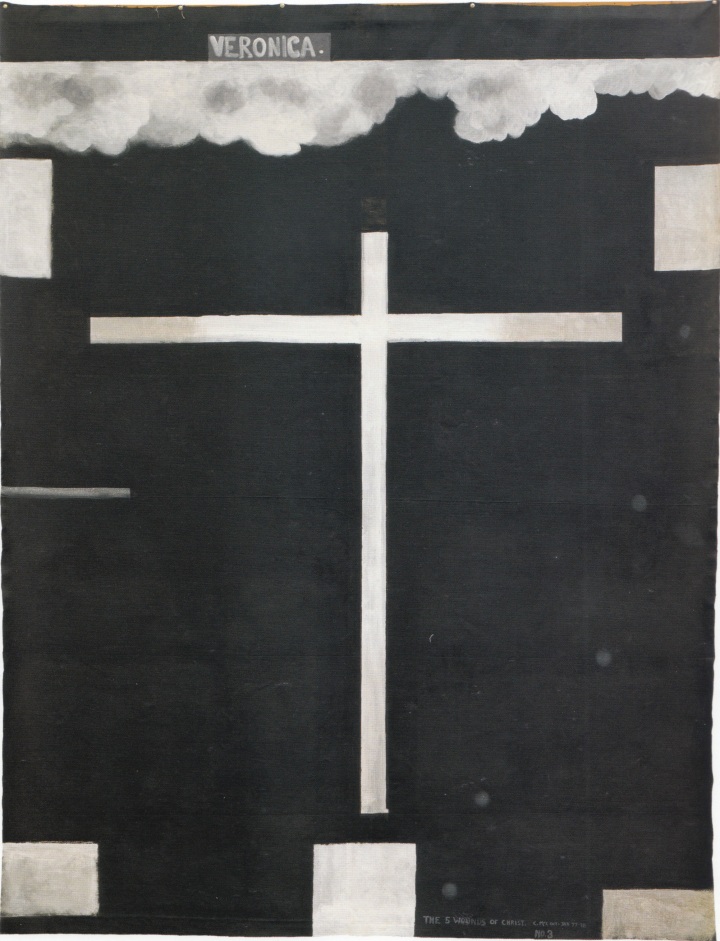

The 5 Wounds of Christ no. 3: Veronica, 1977-78.

Acrylic on unstretched canvas, 242 x 187.5cm.

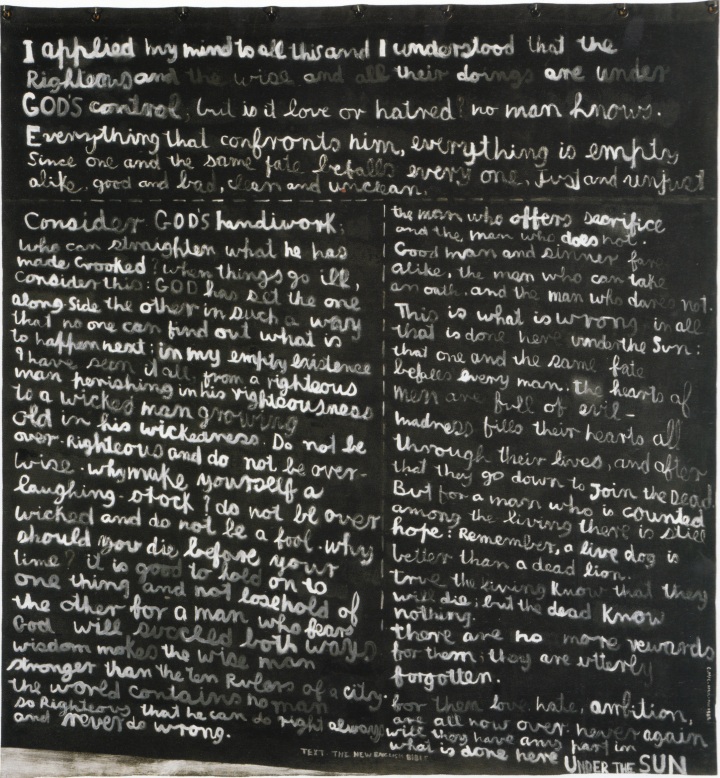

I applied my mind, 1980-82.

Acrylic on unstretched canvas, 195 x 180.5 cm.

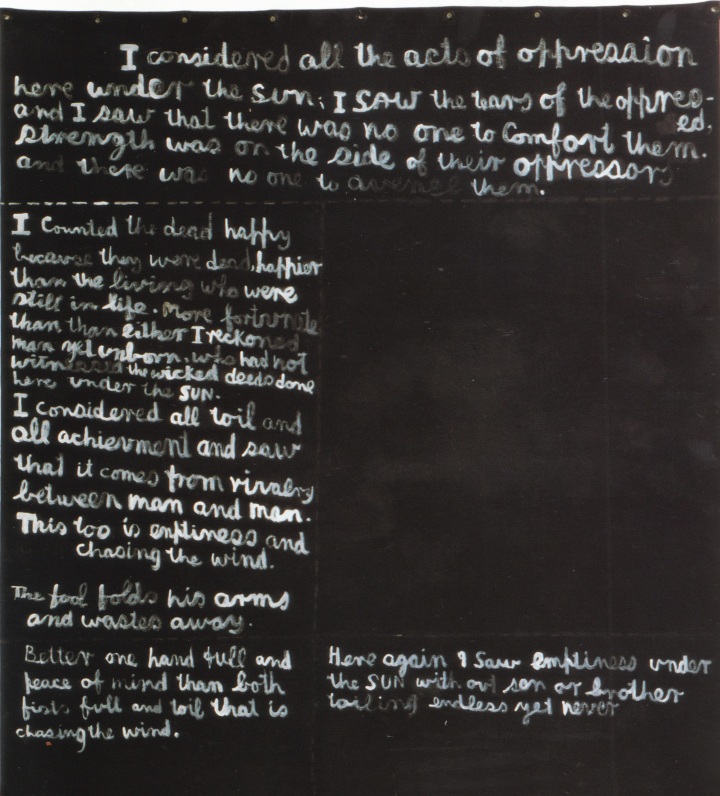

I considered all the acts of oppresssion, 1980-82.

Acrylic on unstretched canvas, 196.4 x 180 cm.

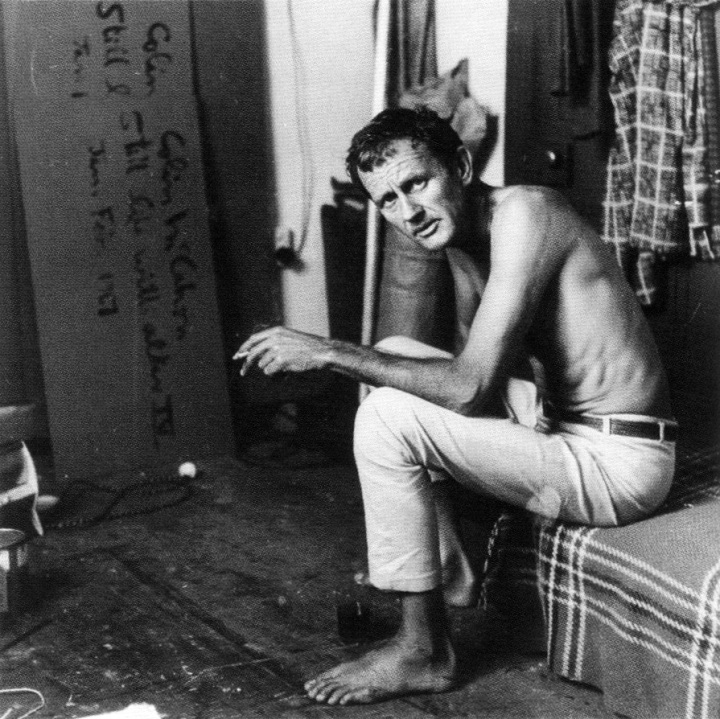

Colin McCahon in the studio at Partridge St. Grey Lynn, Auckland, late 1960s. Courtesy of McCahon Family Archive.

There is a word from the time of the cathedrals: agape, an expression of intense spiritual affinity with the mystery that is ‘to be sharing with another life’. Agape is love, and it can mean ‘the love of another for the sake of God’. More broadly and essentially it is a humble impassioned embrace of something outside the self, in the name of that which we refer to as God, but which also includes the self and is God.

Barry Lopez, Arctic Dreams (London: Picador, 1986)

Driving east from Murupara you can watch the landscape suddenly slip from the grip of the great colonial project. Pastoral plain and pine plantation yield to the primordial, as abruptly as tarseal becomes loose gravel. Up against the wild forcefield of Te Urewera, Britain of the South just gives up.

It is different here, and Colin McCahon knew it. The West’s cataclysm of chance has been through Te Whāiti, Ngāputahi, Ruatāthuna, and Maungapōhatu, as it has every Pacific village. But dispossession here, as with the empires potentials for obliteration, has had but a shadow of it’s success elsewhere in Aotearoa. Te Urewera’s Māori land lies without the gangs of Pākehā farms that now inevitably surround it in other New Zealands, and remains unfazed by their urgent economics. It is as though Tūhoe’s history, their mountain fortress’s inaccessibility, has given them a strength that still sustains. While what now saturates the rest of the country may circle Te Urewera on all sides, it can’t enter. It is as though the land’s life-force is still Māori.

Yet somehow the possibility is betrayed by the way the Māori clearings seem to shrink from what encircles them. The driver too feels diminished by the wild life outside, compared with the passage through a domesticated landscape. Road maps confirm what the view hints. This is the South Pacific, not England. A dark, elemental, forever forest, not to be entered unless you know precisely what you’re doing. Primordial, Gondwanan, shrieking with birds, but unhaunted by the human history that brings time – or landscape – into being. Pacific gods – Papatūānuku, Tāne – have a longer stake in it than Christianity’s one, but the distinction is trivial. This has long been its own place. Brutal news for those who like to call the landscape theirs.

…

Colin McCahon’s eyes needed more than picturesque forest scenery. His peering out of the car window – a constant I gather – was a vital part of his process of looking into ‘New Zealand’, our situation here, and figuring out how to show it to us. His pictures, as he called them, can take the wind out of us, exposing the damage to what another discomforting voice, the cartoonist Michael Leunig, calls our soul’s ‘great, delicate, interconnected ecology’. McCahon was scared by the huge gap in our practical knowledge of ourselves in these ancient islands – dislodging what was here by nature without learning much about it – created by the settler psyche and pieties. ‘Something logical, orderly and beautiful’: these now-celebrated words express his earliest conscious sensing of qualities ‘belonging to the land but not yet to its people. Not yet understood or communicated, not even really invented.’ he meant Pākehā people, in the main, and he decided he would be the inventor. In the process, he created himself an envoy of the power and magic of art such as New Zealand had not experienced before.

Really good art burns itself into your memory and shapes your sense of place. Colin McCahon knew that his encounter with this stretch of country and its diminishing of human projects produced something seminal.

…

Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad’s famed exposé of colonial misdemeanor in Africa, has been label an inveterate piece of racist imperialism. But the darkness Conrad sensed in ‘the primeval forest’, as impenetrable as the darkness in Congo eyes, was not a phenomenon confined to the African arm of the empire. D.H. Lawrence sensed in Australia what Monte Holcroft called ‘the primeval shadow’ here, McCahon painted it, and, inevitably in a culture that is in decolonisation mode and has such a hard eye for tall poppies, some have used that to have a go at him. His inventions have been branded ‘Pathetic Projections: Willfulness in the Wilderness’ by those who detect in them a presumption to be the first speaker in and otherwise ‘silent’ land – a thousand years of Māori settlement notwithstanding.

Yet Colin McCahon’s ‘deeply coded community of signs’ have been compared to Aboriginal songlines. Just as few imagine ecology as being a site for finding answers to the question of whether peace can be a foreground rather than background, landscapes are full of things that most people simply don’t see. Some may look at the landscape and notice the light and the dark, the vulnerabilities and regenerative life forces in the shifting, chancy interplay between culture and nature. The appearance in the mind, even, of a symbol or two. But they’re more likely to move onto another view before the prospect can affect them. Moving left to right, those who would enter his landscapes, must walk along them as Pitjantjtjara and Aranda do their songlines, being cued in to who and where they are, where they came from, and how they relate to what’s going on.

Colin McCahon once said that his landscapes weren’t landscapes. But in interpreting a place through symbol and imagination, they heighten our own perceptions in ways that are rarely permitted by the ordinary process of ‘seeing’. Eyes feeding on the wildness pressing in on him, he came along this road because these dark, primal Aotearoan hills has something to tell, and he’d been asked tell it. Seeking truth in a peculiarly hard place.

…

‘Of the reasons for preserving a fragment of the landscape,’ one of the most insightful readers of landscape has said, ‘the aesthetic is surely the poorest.’ Waikaremoana is particularly beautiful New Zealand scenery, in the midst of what Elsdon Best, writing for tourists, called a ‘picturesque region’. But McCahon was suspicious about beauty of that kind. In a national park, of all places, he seeks to take us out of the world of visibly charged beauty – showing New Zealanders how their preoccupation with scenery, their possessing it ‘preserved’ in reserves, and their dogma that it’s a necessary ingredient of a painted landscape, trapped them in a particular sense of beauty.

‘How to keep… Back Beauty, keep it, beauty, beauty, beauty… from vanishing away?’ asks a poem McCahon was fond of quoting. ‘Give beauty back, beauty, beauty, beauty, back to God, beauty’s self and beauty’s giver.’ We do not own what appears to be most ours, most easily grasped, says Gerald Manley Hopkins, the poet. We have no claim on it – ‘preserving’ it for example – because what is at risk does not belong to us anyway.

What McCahon called his ‘interest in landscape as a symbol of place and also of the human condition’ was central to Hopkins poetry. Hopkins considered the filtering inward of nature to self that he recorded in his contemplations of nature to be so crucial to real understanding that he coined a word for it, a word now used by poets, painters and ecologists alike.

‘Inscape’ is the unfolding of the particularities of nature and the lineage of our encounters with it that put sensory perceptions of a landscape trigger. It’s the antithesis of what strangers’ eyes perceive, ‘unknown and buried away… and yet how near at hand it was if they had eyes to see it’, Hopkins wrote. Inscape distinguishes ‘the Māori landscape’ from the Pākehā one. It allows for both despair and delight at the sight of manuka-covered hillside in the bloom of regeneration. It makes those in New Zealand who are of European descent aware that their colonial project brought an inner landscape, so to speak, across the world, and one which differed at every point from what they found here. It was a kind of self-protective psychological compensation, the Australian Judith Wright has ventured, that made us burn, shoot, chop down and destroy whatever we could, replacing it, ‘if at all with something nearer to the heart’s desire’.

Hopkin’s poetry has been labeled linguistic nationalism for its profound shift from the standard Latin ‘correctness’ of mid-nineteenth century Catholic England to vernacular dialects of Anglo-Saxon folklore and custom. McCahon drew long and sustainingly from Hopkins for much of his painting life, and equivalent nationalism emanates from his landscapes’ candid hostility to the saturating prevalence and power of ‘the picturesque’ in New Zealand landscape painting rules. Inscape, said Hopkins, is ‘the very soul of art’. And just as, without that, he could not describe, in words, the processes and relationships he saw around him, McCahon, similarly, had to devise his own enabling vocabulary of signs.

– you bury your heart, and as it goes deeper into the land

you can only follow. It’s a painful love,

loving a land.

It takes

a

long time.

‘I belong with the wild side of New Zealand’ – The flowing land in Colin McCahon.

Originally written as a commissioned essay for a book to accompany a major exhibition of Colin McCahon.

The exhibition did not eventuate.

Theatre Country: Essays on Landscape and Whenua

Geoff Park

Victoria University Press

2006

___

Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith

Marja Bloem and Martin Browne

Contributions by Rudi Fuchs : William McCahon : Murray Bail : Francis Pound : Steven Miller

Craig Potton Publishing

2002

___

R

Note: This will be the last post on History of Our World.

To those who viewed, commented or supported the website, thank you.

Earth on Fire | Bernhard Edmaier

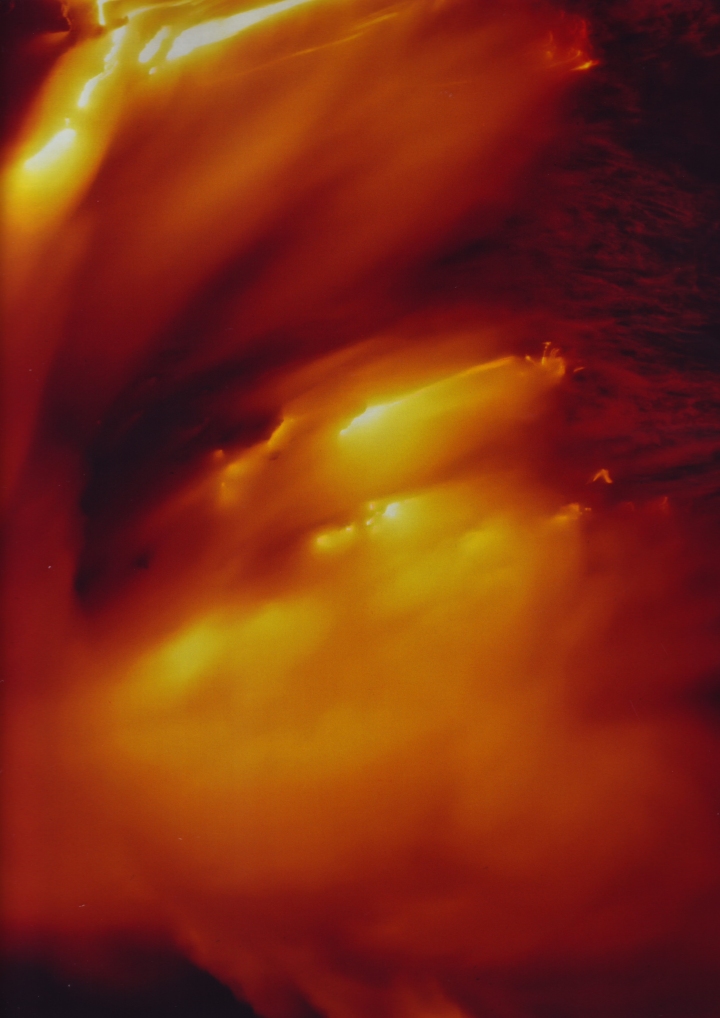

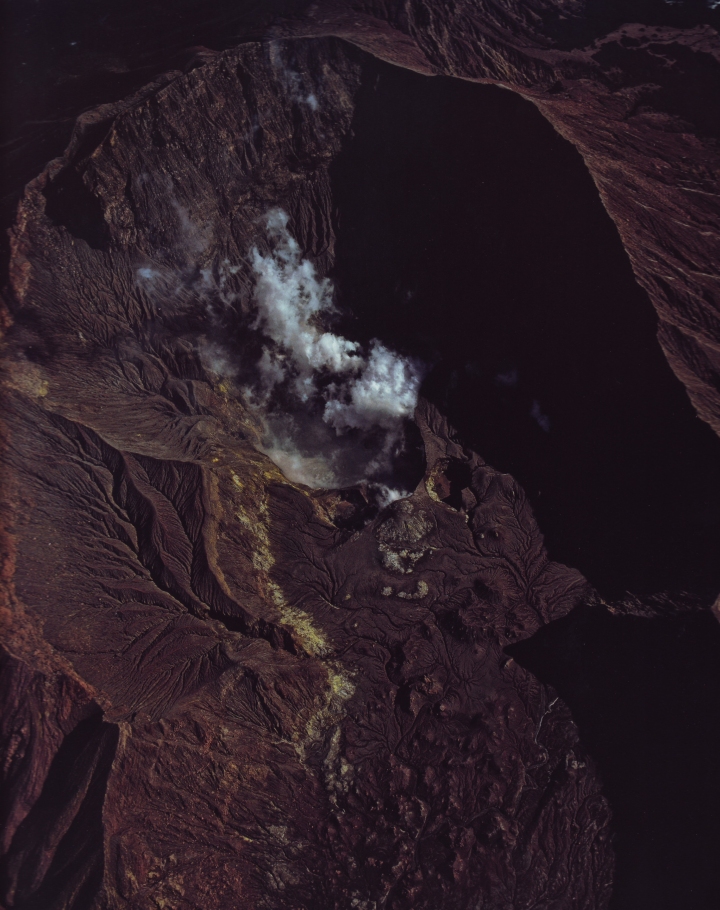

Santiaguito, Guatemala.

Kilauea (Big Island), Hawaii.

Skeiðarárjökull, Iceland.

White Island, New Zealand.

Fossa Crater (Aeolian Islands), Italy.

Erta Ale, Ethiopia.

Landeyjarsandur Estuary, Iceland.

Mount Etna, Italy.

Nyamulagira, Democratic Republic of Congo.

___

Earth on Fire

Bernhard Edmaier

Phaidon Press Inc.

2009

___

A

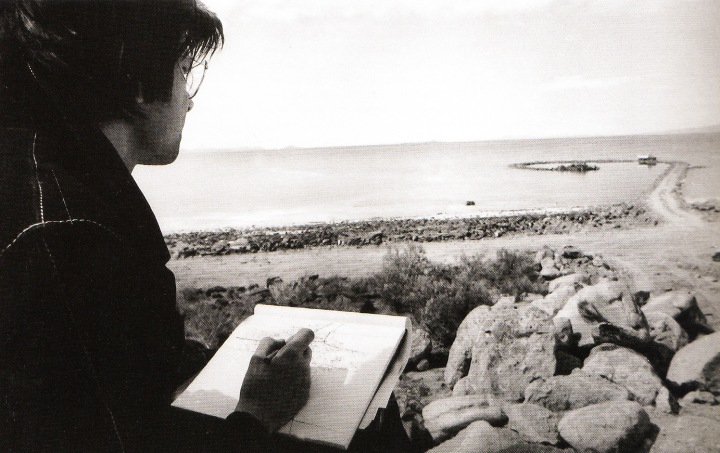

Robert Smithson

Aerial view of Spiral Jetty (1970), Great Salt Lake, Utah, August 2003. Mud, precipitated salt crystals, rocks and water. Coil: 1500 ft. long and 15 ft. wide. Photographed by David Maisel.

Smithson building Spiral Jetty (1970), Great Salt Lake, Utah, 1 April 1970. Photographed by Gianfranco Gorgoni.

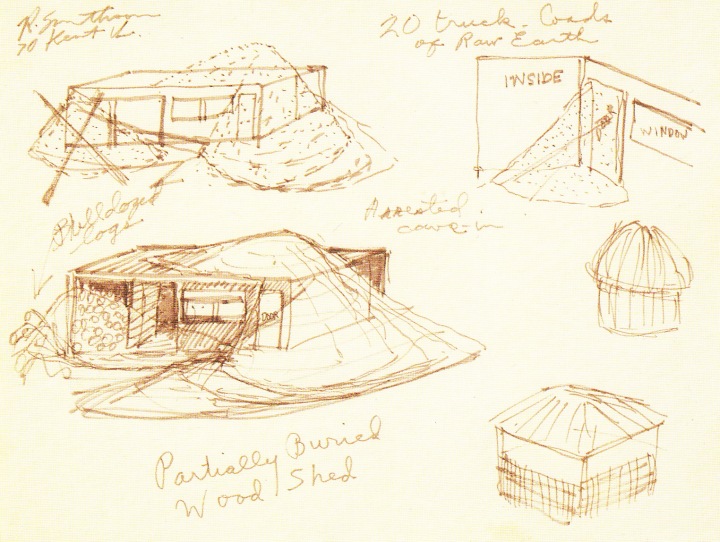

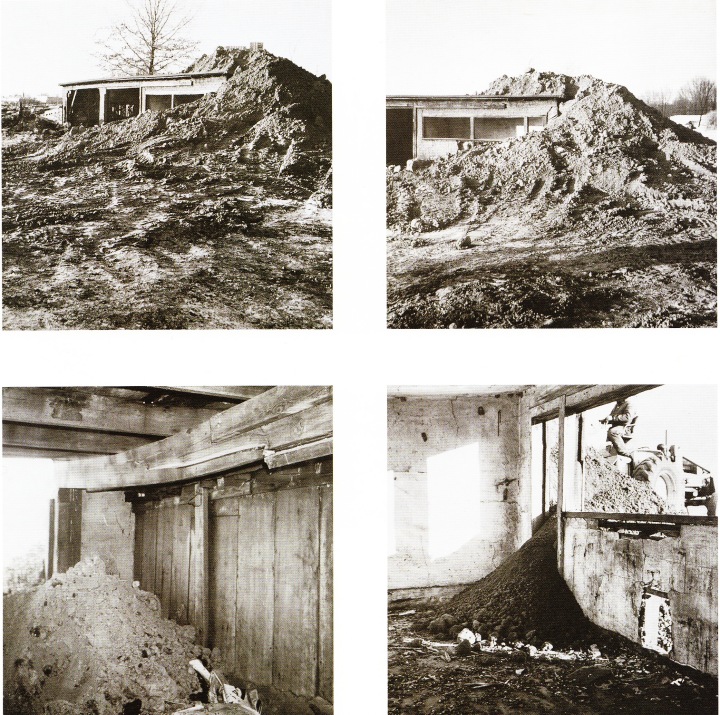

Documentary Drawings for Partially Buried Woodshed, 1970.

Partially Buried Woodshed, 1970.

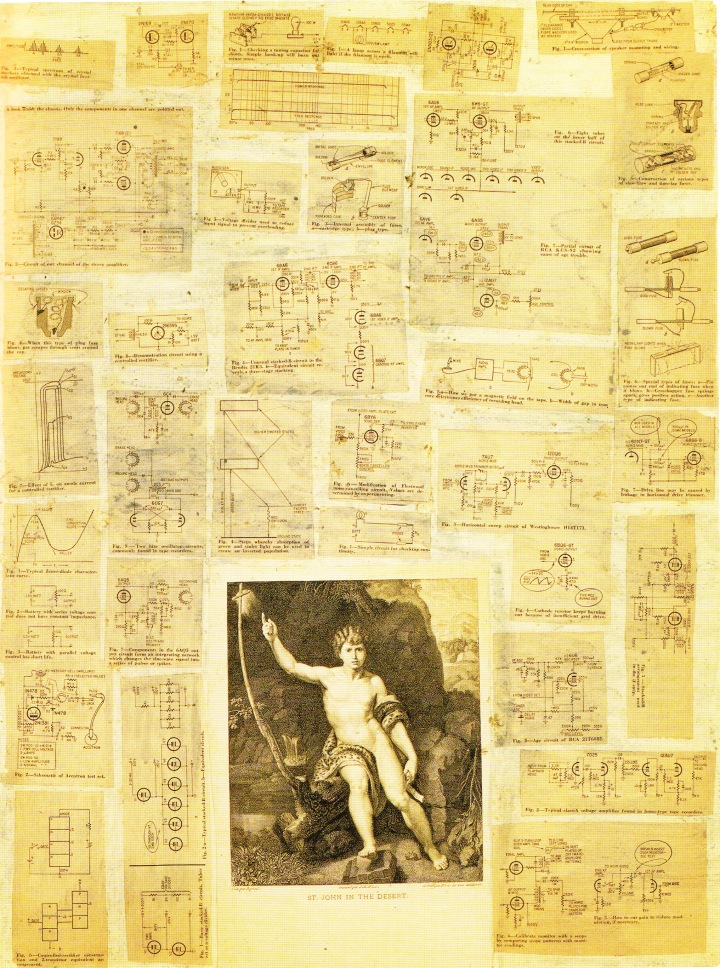

St. John in the Desert, c. 1961-63.

Untitled (Mica Spread) (1970), Rozel Point, Utah, April 1970. Photographed by Nancy Holt.

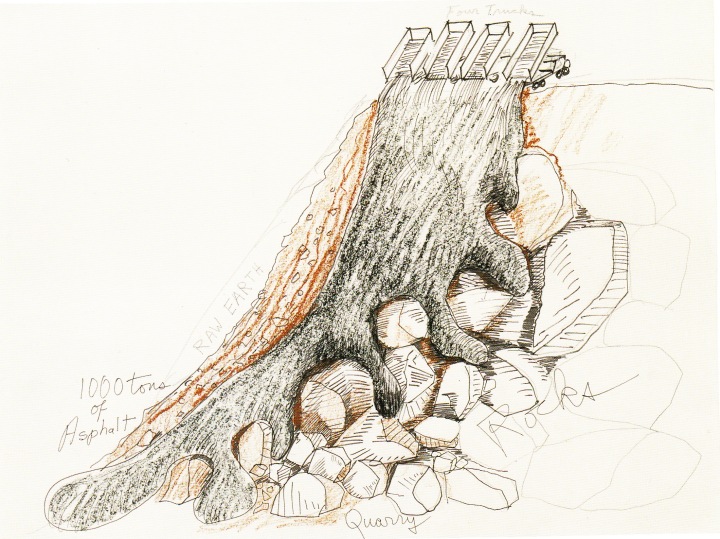

1000 Tons of Asphalt, 1969.

Asphalt Rundown, Rome, 1969.

Spiral Jetty (1970), Great Salt lake, Utah, 1970. Mud, precipitated salt crystals, rocks and water. Coil: 1500 ft. long and 15 ft. wide. Photographed by Gianfranco Gorgoni

Smithson at the site of Spiral Jetty (1970), Great Salt Lake, Utah, April 1970. Photographed by Gianfranco Gorgoni.

Robert Smithson is perhaps best known as a pioneer of the Earthworks movement and the creator of the iconic Spiral Jetty (1970). However, his involvement in the development of Earthworks is only one of his many contributions to postwar American art. One of the most important concepts Smithson was that of the “site,” a place in the world where art is inseparable from its context. His sites included remote locations like Rozel Point, on the north shore of the Great Salt Lake; the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico; the art museum and the white cube of the gallery; and the pages of art magazines like Artforum, where he published some of his essays. By encompassing both conventional exhibition venues and far-flung locations within his practice, Smithson performed a kind of institutional critique, pointing to the geographical and cultural limitations that the purportedly neutral spaces of museums impose on art.

___

Robert Smithson

Eugene Tsai : Cornelia Butler

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

2005

___

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

B

Doug Aitken

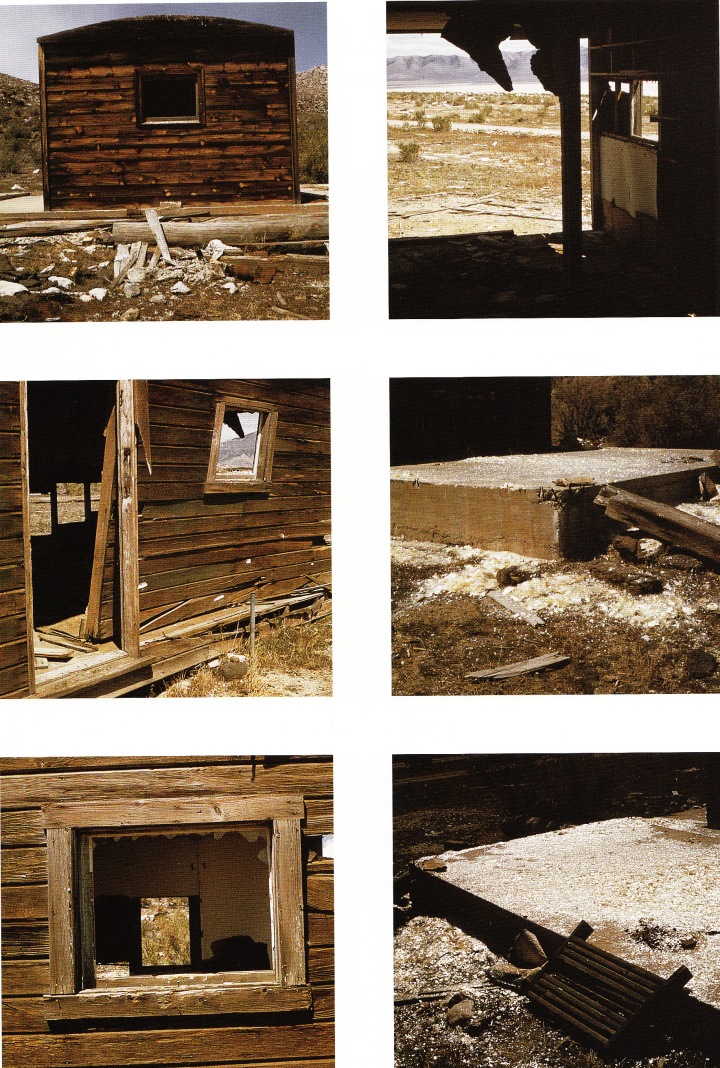

Blow Debris, 2000. Colour film transferred to 9 channel digital video installation, colour, sound and architectural environment, 21 min. cycle.

Electric Earth, 1999. Colour film transferred to 8 channel laserdisc installation, colour, sound, 9 min. 50 sec. cycle.

Electric Earth, 1999. Colour film transferred to 8 channel laserdisc installation, colour, sound, 9 min. 50 sec. cycle.

Who’s Under The Influence, 1999. Diptych.

Glass Barrier, 2000. C-print mounted on Plexiglas.

Diamond Sea, 1997. Colour film transferred to digital video, 3 channels, 3 projections, 1 monitor, Duratrans backdrop, sound and architectural environment, 10 min. cycle.

Diamond Sea, 1997. Colour film transferred to digital video, 3 channels, 3 projections, 1 monitor, Duratrans backdrop, sound and architectural environment, 10 min. cycle.

2 Second Separation, 2000. C-print mounted on Plexiglas.

Eraser, 1998. Colour film transferred to 7 channel digital video installation, sound and architectural environment, 20 min. cycle.

Amanda Sharp: Director Werner Herzog once explained that his book On Walking in Ice (1979) came about when he found out that a friend of his was dying in Paris. Herzog decided that if he walked from wherever he was – I assume Munich – to Paris, his friend lived: he felt he could keep his friend alive by walking. A work like this is about how individuals can attempt to alter – slow down or speed up – time, how they’re somehow part of a much bigger system.

Doug Aitken: We all encode our experiences of time at different rates. A single moment from several months ago may consume our thoughts, yet a whole summer five years ago may have completely vanished from our memory. We stretch and condense time until it suits our needs. You could say that time does not move in a linear trajectory, and moreover we’re not all following time using the same system.

When I was twenty-one I worked in an editing room for the first time. We were working long hours, day and night, but for me it was a new sensation, fresh and exciting. When finally I could go home to sleep, my dreams were extremely vivid. As I was moving through a dream, I would look down in the lower right hand corner of my dream and see numbers: a time code, like the date-time-minute-frame numbers used in editing raw footage. I was surprised I had never noticed this time code in my dreams before! I also recognized that I no longer needed to watch and witness my dreams passively; I could stop my dream like a freeze frame and look around as if watching a giant, frozen photograph. I could pull back and the dream would rewind so that I could reassemble it in new ways. That night I re-edited my dreams over and over again.

I suppose my working process is very nomadic. I’m not interested in working out of a sterile, traditional, white-cube studio. I’d like to find a methodology that is constantly sight specific, constantly in flux. Some works which are very fictional demand to be built and constructed as if part of a new reality, while others require an intense investigation into a specific landscape. I would like the permanence of my process to be as temporary as possible. I’d like to think of an absence of materialism where at the end of the day, all one needs is a table, a chair, a sheet of paper,possibly less. That would be nice: to be without routine and unnecessary possessions.

Uprooting and removal surrounds us, and at times these can be mirrored in our working process. At times I just let go and am assimilated into my landscapes, other times I feel an active resistance. I think there’s something about growing up in America that makes you feel nothing is ever really stationary. Home can be motion at times*.

*Excerpt from Amanda Sharp in conversation with Doug Aitken.

___

Doug Aitken

Daniel Birnbaum : Amanda Sharp : Jörg Heiser

Phaidon

2005

___

B

9 comments